How rare it is to feel that a show of contemporary paintings can delight the most discerning art lovers you know, and please those who’d rather clean an oven than enter an art gallery. The retrospective of work by Kurt Solmssen, “The Yellow Boat” exhibit, now running through September 22 at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, inspires this unique sensation.

Stylistically, Solmssen works mostly in the plein air landscape tradition. With his commitment to realism, a strong sense of place, and a fondness for domesticity, his work brings to mind Fairfield Porter, or at times Edward Hopper minus the sadness. In a departure from this tradition, Solmssen works in large format—no easel could hold these canvases. But Solmssen also embraces abstraction and even minimalism—he cites Richard Deibenkorn and Morris Graves as influences.

Stylistically, Solmssen works mostly in the plein air landscape tradition. With his commitment to realism, a strong sense of place, and a fondness for domesticity, his work brings to mind Fairfield Porter, or at times Edward Hopper minus the sadness. In a departure from this tradition, Solmssen works in large format—no easel could hold these canvases. But Solmssen also embraces abstraction and even minimalism—he cites Richard Deibenkorn and Morris Graves as influences.

In terms of place, there’s a difficulty again: Solmssen is clearly rooted in the Pacific Northwest, living and working in the southern reaches of Puget Sound, on land that’s long been in the family. But Solmssen was born and raised near Philadelphia, and he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It shows: he embodies the spirit of that region and its traditions just as much as he lets the Salish Sea inform his work.

Solmssen’s paintings seem unmoored from historical time. In the world they depict, it might be 2021 or 1921. The canvases simply don’t care about the age they are painted in. What they care about is the hour of the day, the particular day of the year, and what the weather is doing or about to do at that moment. You don’t see power lines in his landscapes, or shiny devices or appliances in his interiors. It’s an unhurried world of rowboats, cut flowers, and well-loved books. And bodies of water, of course, since Solmssen’s home is in Vaughn, Washington, which sits along a protected bay near the end of the long and secluded Case Inlet. Solmssen covers the waterfront, but from a hammock.

Bainbridge Island Museum of Art is an ideal venue for the retrospective. A typical Solmssen painting is large-scale—some diptychs measure ten feet wide—and the museum has the space these canvases need. Most of Solmssen’s work is genial and recognizably of the region, qualities that pair well with museum’s own personality and values. The museum looks out onto Eagle Harbor and its boats, not quite a Solmssenian view, but not so far off either.

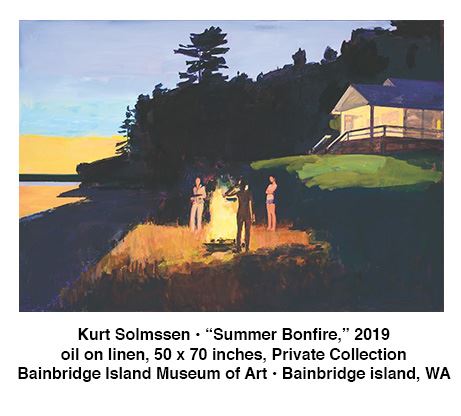

BIMA Chief Curator Greg Robinson and Associate Curator Amy Sawyer have three decades of work to highlight, and they have arranged their selections artfully. Two bright canvases greet you at the ground floor reception lobby, where they establish a warm and accessible tone. The retrospective begins in earnest on the second floor, with small format paintings of the titular yellow boat on display in the Beacon gallery. The show then heads into the Rachel Feferman gallery, where you immediately encounter “Summer Bonfire.” In this picture, friends gather around a beach bonfire on a summer evening; the sunset’s faded glow is caught in a low bank of clouds to the east, and up at the darkened house a porch light is on—Solmssen deals with multiple light sources, but captures one mood.

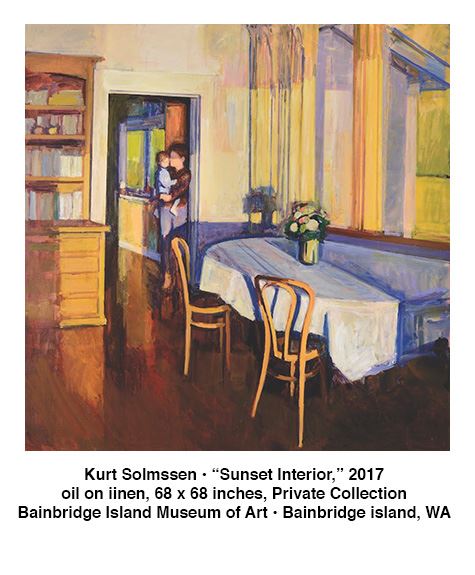

At the spatial center of the gallery you find Solmssen’s interiors. These are peaceful scenes of family members reading or sleeping. Here the palette is subdued and the sunlight softened. (These folks love books: if they aren’t reading one, they are posing beside or below a substantial bookshelf.) The hygge is strong in these scenes, and yet the paint and the brushwork is restless and unresolved.

At the spatial center of the gallery you find Solmssen’s interiors. These are peaceful scenes of family members reading or sleeping. Here the palette is subdued and the sunlight softened. (These folks love books: if they aren’t reading one, they are posing beside or below a substantial bookshelf.) The hygge is strong in these scenes, and yet the paint and the brushwork is restless and unresolved.

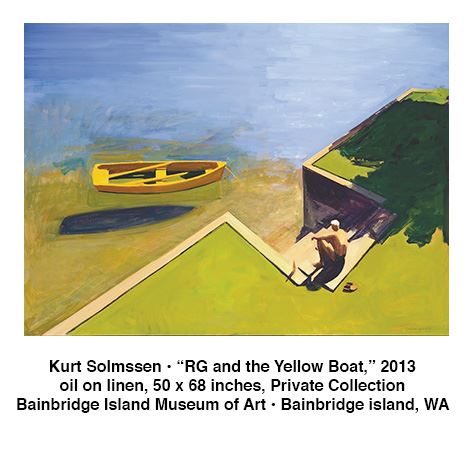

Next comes paintings centered on the yellow boat. It’s the star of the show, or at least its anchoring motif. You may have spotted the boat in the background of other paintings; here the boat is ready for its close up. (Some of the paintings can’t include the boat, because they are scenes viewed from the boat.) One thing about this vessel: it is always empty, and you might wonder why that is. But in a sense the boat is occupied after all—by its oars. They function like limbs that give the boat a kind of body language. Solmssen is also playful with the boat’s reflection, and with its shadow (which falls sometimes on the bottom of the bay).

The rowboat may or may not be the highlight of the show for you, but the show is not over. Continue on to the deepest part of the gallery where you find Solmssen’s most abstract pieces. Here are chilly scenes of winter, of mornings so dense with fog that the world is formless and sunless; the paint dissolves distinctions between land and water, figure and ground. The rain and snow in which they were painted are likely mixed in with the pigments. The contrast with the preceding work is startling, an unexpected coda in a minor key. These monochromatic works may prompt you to circle back through everything you’ve already seen with renewed appreciation for the blessings of color and light.

It was on a densely foggy morning 60 years ago or more that Solmssen’s grandfather lost his rowboat, his prized possession. Or at least lost sight of it for a long time, until the weather cleared. When the rowboat turned up again, he hit upon a creative solution: paint the boat a bright yellow. Make it brightly visible.

See how well the plan worked out, how visible the boat has become, and how well seen. The Solmssen family has long had a way with color.

Tom McDonald

Tom McDonald is a writer and musician living on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

“The Yellow Boat” exhibit is on view daily from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. at Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, located at 550 Winslow Way East on Bainbridge Island, Washington. For more information, visit www.biartmuseum.org.