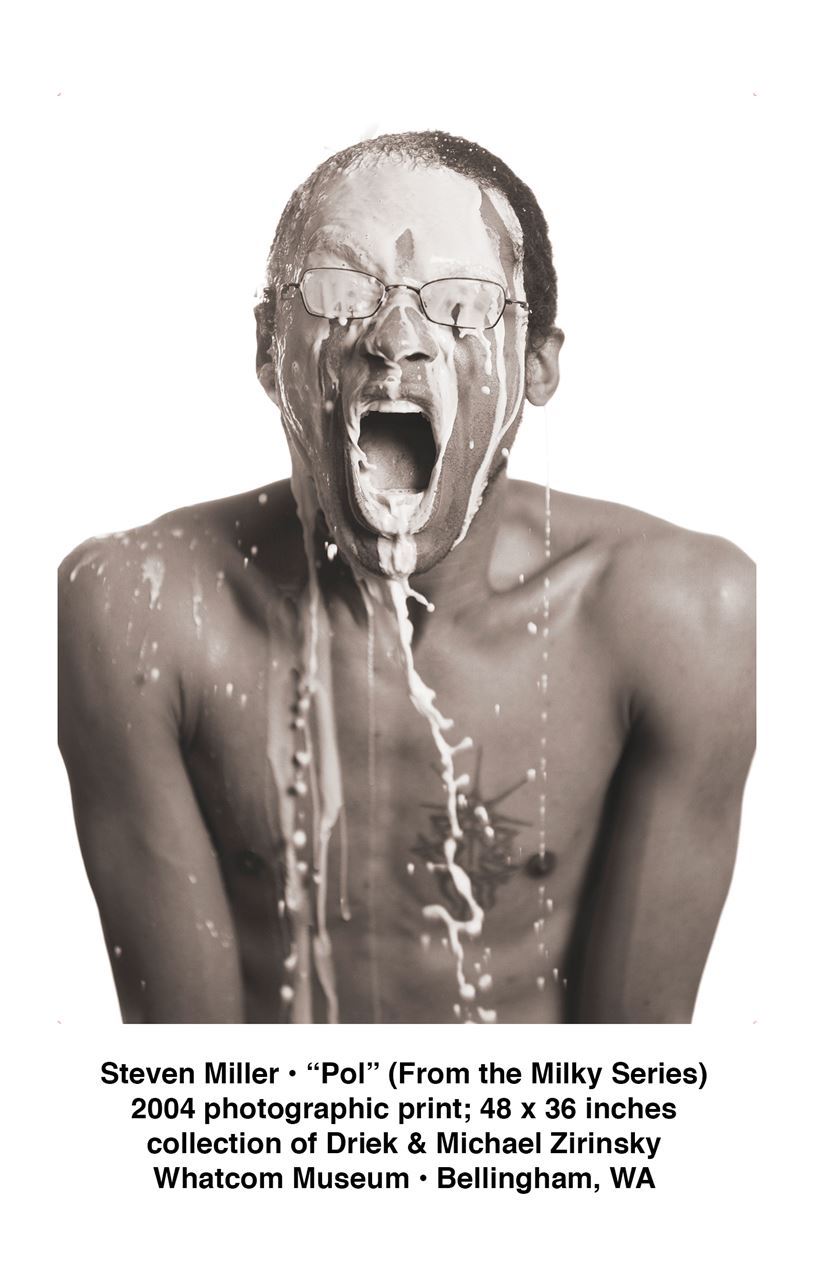

.jpg) How has your perception of your sense of “self” changed over the past two years? Has this time been a pivotal period of image-making or remaking? We all seem to have gained a new awareness of our body and how we can impact the bodies of others during this pandemic. As people start to physically gather again, how will these lessons impact our future interactions? In the exhibition, “Up Close & Personal: The Body in Contemporary Art,” visual representations of the human body take on renewed significance. How artists and their subjects see themselves and choose to portray the physical, and emotional, self is on display in the museum. The exhibition is from the collection of Driek and Michael Zirinsky, which adds a layer of interest to the selections. What can we learn about ourselves by the artworks that resonate with us, but also why did the collectors select these specific artworks for their collection? All these questions circle around a central figure: the ever complex and analyzed human body.

How has your perception of your sense of “self” changed over the past two years? Has this time been a pivotal period of image-making or remaking? We all seem to have gained a new awareness of our body and how we can impact the bodies of others during this pandemic. As people start to physically gather again, how will these lessons impact our future interactions? In the exhibition, “Up Close & Personal: The Body in Contemporary Art,” visual representations of the human body take on renewed significance. How artists and their subjects see themselves and choose to portray the physical, and emotional, self is on display in the museum. The exhibition is from the collection of Driek and Michael Zirinsky, which adds a layer of interest to the selections. What can we learn about ourselves by the artworks that resonate with us, but also why did the collectors select these specific artworks for their collection? All these questions circle around a central figure: the ever complex and analyzed human body.

To say that this exhibition simply showcases portraiture is a mistake. There are contemporary portraits in the exhibition that demonstrate the more traditional aspects of portraiture: the artist creates a visual representation of a subject and there are clues about the person’s identity or values included in the artwork. But these are contemporary images that are also evoking ideas about identity, race, sexuality, politics, and more. Many of these images are intimate and personal, like Titus Kaphar’s “Womb,” a tar on paper portrait of a pregnant Black woman. The artist includes aspects of her clothing to give the viewer clues about the time period (likely 19th century), but her breasts and unborn child are on full display as if the viewer has x-ray vision. They are let into this private moment as the subject looks off into the distance. We are left to consider what she may be feeling as the birth approaches. Is she fearful? Hopeful? It is difficult to tell.

As the viewer continues through the exhibition, there is a text panel to remind us that artists use the figure to tell narratives. Not all figurative art is portraiture, but the figure is a powerful tool in storytelling because they can connect people. If viewers can see themselves in an artwork, maybe that will help them connect to each other in deeper way. One method used to create this connection is by obscuring the figure so that the individual is not recognizable. They become a shell for the viewer to inhabit. Noah Davis erases the identity of the person in his painting, “I Wonder as I Wander.” A figure leans against a pedestal and cradles a sculpture in their arm. The background is black, and the artist has allowed the paint to drip and spread across the canvas, which gives the impression of deterioration. The face of the individual is overcome by dark background and is completely hidden. Who is this person? Their identity has disappeared, allowing the viewer to insert themselves into the work. What can we learn about figures in society who are erased? Whose futures are being extinguished? The artist pushes the viewer to think about these questions.

It is disconcerting to see important physical elements of a figure obscured from view, and it can be disturbing or visually alarming when the body appears to be dissected in an image. There is an entire part of the exhibition devoted to “figure fragments” which analyzes artworks that focus on certain elements of the body. The element may carry historical or social significance, such as the raised fist in Samantha Wall’s “Fists” from her “31 Days” series. While Wall highlights one body part to focus our attention on it, Mark Calderon hides a child’s face in “Regalis (red)” while also exposing their nakedness. The figure’s legs are crossed as they appear to float alone against a white background. The arms are drawn into the body and the face is cut off to bring the body flush against the wall. The child is completely physically vulnerable, and their existence is puzzling.

It is disconcerting to see important physical elements of a figure obscured from view, and it can be disturbing or visually alarming when the body appears to be dissected in an image. There is an entire part of the exhibition devoted to “figure fragments” which analyzes artworks that focus on certain elements of the body. The element may carry historical or social significance, such as the raised fist in Samantha Wall’s “Fists” from her “31 Days” series. While Wall highlights one body part to focus our attention on it, Mark Calderon hides a child’s face in “Regalis (red)” while also exposing their nakedness. The figure’s legs are crossed as they appear to float alone against a white background. The arms are drawn into the body and the face is cut off to bring the body flush against the wall. The child is completely physically vulnerable, and their existence is puzzling.

The exhibition provokes intriguing questions about our physical existence, how meaning is applied to the physical, and the various historical and social implications interwoven with body representations. There are these layers of questions on top of the fact that these works are all from the same private collection. Not only do Driek and Michael Zirinsky collect important contemporary artists, but there is a through line in their collecting that deserves further attention. What is it about figurative work that interests them? What is it about figurative work that interests you?

Chloé Dye Sherpe

Chloé Dye Sherpe is a curator and art professional based in Washington State.

“Up Close & Personal: The Body in Contemporary Art” is on view Thursday to Sunday from 12-5 P.M. through February 27, at Whatcom Museum’s Lightcatcher Building, located at 250 Flora Street, in Bellingham, Washington. For more information, visit www.whatcommuseum.org.