Kenjiro Nomura (1896-1956) came to the United States from Japan at the age of ten and was left to fend for himself in Tacoma at the age of 16 when his family returned to Japan in 1913. Two years later, he moved to Seattle and began to formally study art in 1915 in the studio of Fokko Tadama. He immediately attracted attention as an artist. At the same time he supported himself with his own sign painting business.

Kenjiro Nomura (1896-1956) came to the United States from Japan at the age of ten and was left to fend for himself in Tacoma at the age of 16 when his family returned to Japan in 1913. Two years later, he moved to Seattle and began to formally study art in 1915 in the studio of Fokko Tadama. He immediately attracted attention as an artist. At the same time he supported himself with his own sign painting business.

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist; An Issei Artist’s Journey” finally gives a major exhibition to an extraordinary artist. Last given a solo show in 1960 at the Seattle Art Museum, his wartime drawings created during incarceration at Puyallup and Minidoka were all hidden away at that time.

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist; An Issei Artist’s Journey” finally gives a major exhibition to an extraordinary artist. Last given a solo show in 1960 at the Seattle Art Museum, his wartime drawings created during incarceration at Puyallup and Minidoka were all hidden away at that time.

Curator of the Cascadia Art Museum, David Martin selected a small group of the over 100 wartime drawings and paintings now in the Tacoma Art Museum as a gift from the Nomura family. (I would like to see a book of all of them!) The exhibition also includes early figurative work, important urban work of the 1930s, and abstractions of the 1950s. The range of the work through incredible challenges is extraordinary.

Barbara Johns’ invaluable book accompanies the exhibit. She eloquently expands on the artist’s career. Both art historians are experts on the Issei and Nissei artists in the Northwest, a unique chapter in American art history. Johns and Martin have published other books. We are so fortunate to have their important work on this subject.

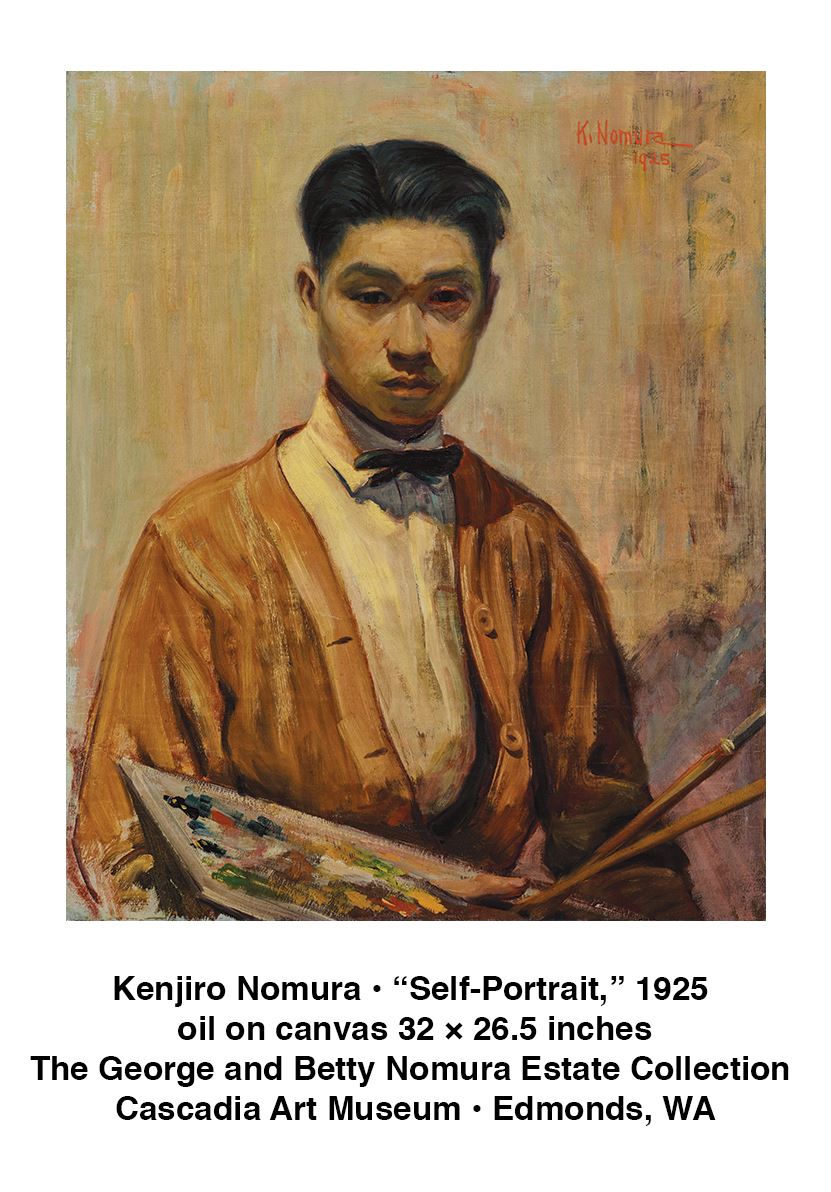

One of the earliest works in the exhibition is an accomplished “Self-Portrait” from 1925. It clearly demonstrates Nomura’s understanding of brushwork and subtle tonalities, but it is not just surface effects. It also suggests an intense inner vitality.

One of the earliest works in the exhibition is an accomplished “Self-Portrait” from 1925. It clearly demonstrates Nomura’s understanding of brushwork and subtle tonalities, but it is not just surface effects. It also suggests an intense inner vitality.

In the 1930s the artist created complex urban landscapes, such as a view of the intersection of Yesler Way and Fourth Avenue, with a sharp eye for planes, angles, and the presence of nature. He layers different tonalities of browns and reds, building a geometric composition with an unusual intricacy of perspectives. I will never see this intersection in the same way again.

Nomura’s work was widely recognized in Seattle and nationally, and even shown at the Museum of Modern Art.

On February 19, 1942, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order 9066 authorizing the relocation of all persons considered a threat to national defense from the west coast of the United States inland. This year marks the 80th anniversary of one of the most brutal executive orders.

On February 19, 1942, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order 9066 authorizing the relocation of all persons considered a threat to national defense from the west coast of the United States inland. This year marks the 80th anniversary of one of the most brutal executive orders.

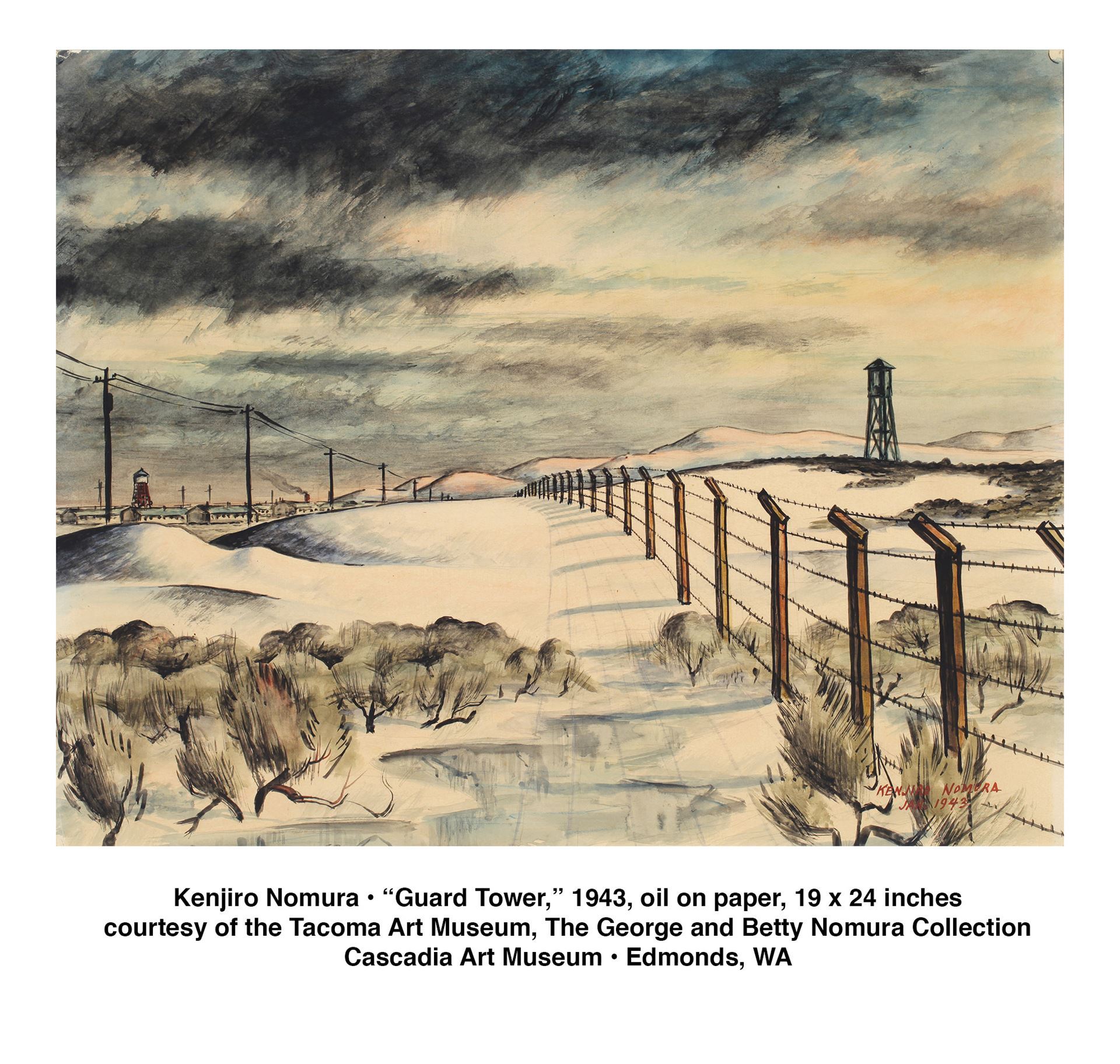

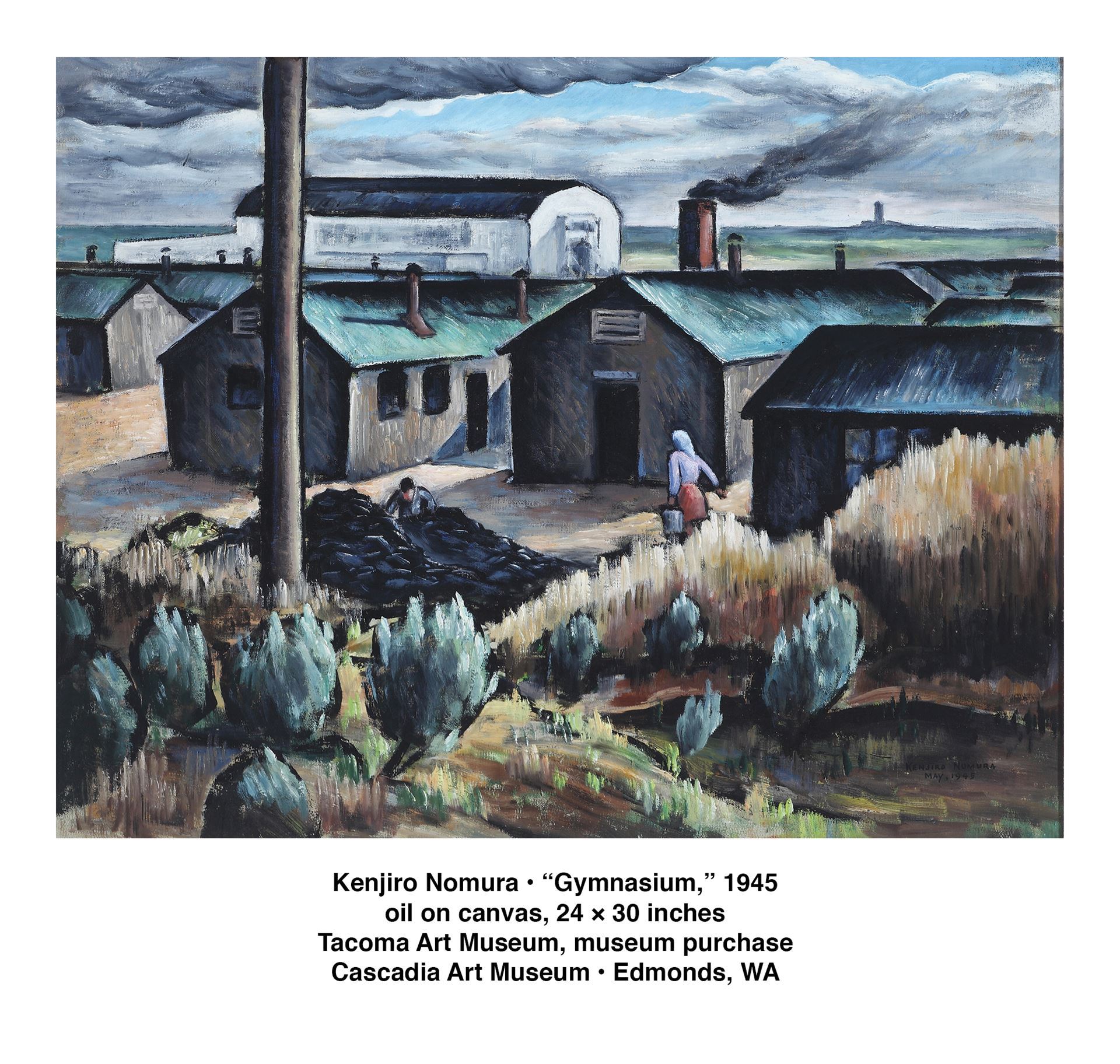

Kenjiro Nomura and his family, along with 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were abruptly uprooted and sent to internment camps, first at the State Fairgrounds in Puyallup and then the remote camp at Minidoka, near Hunt, Idaho where he remained until the end of World War II. But, incredibly, he never stopped painting, making a unique record in watercolor of both camps.

These factual and haunting images record the ordinary lives of the camps, a barber shop, a mess hall, an outhouse, barracks and a water tower. But the scenes always include nature. Nomura even painted pure landscapes. As Johns recounts in her book, the internees at Minidoka were expected to take the sagebrush-filled land and turn it into rich agricultural farms with irrigation ditches dug by hand. They produced millions of pounds of produce, and Nomura records this transformation in several watercolors. But I found his tiny sunsets, views of the sky through a barrack window, the sun bursting through from the sky above the barracks, a sign that he never stopped looking beyond his situation. The persistence he had developed as a teenager when left alone in this country served him well.

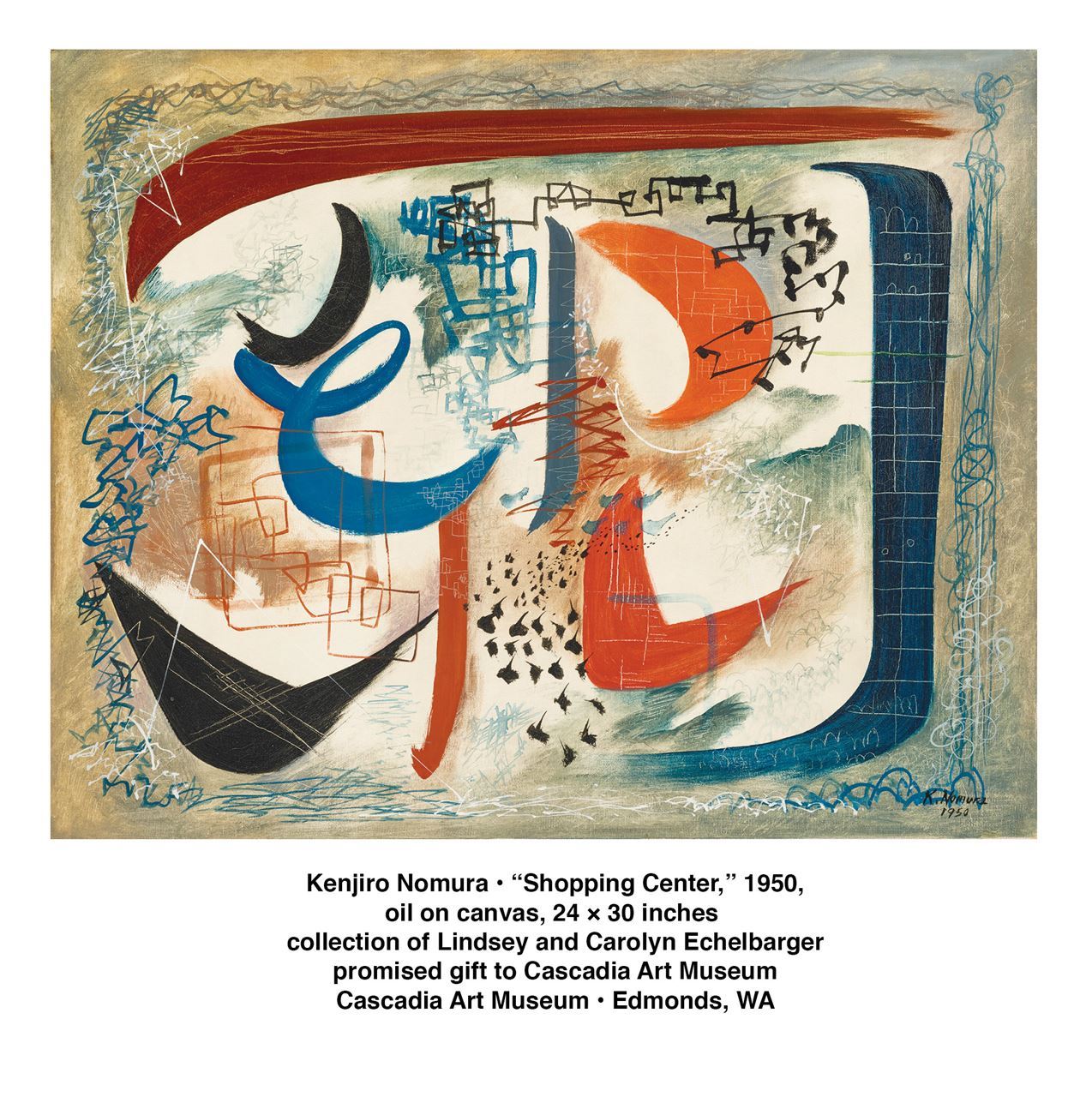

After the internment, Nomura returned with his family to Seattle in 1945. He once again overcame incredible misfortune after his wife committed suicide and his second wife died. But with the encouragement of fellow artists, particularly Paul Horiuchi, he resumed painting. In the 1950s, he turned to highly original abstraction. Each painting demonstrates a new experiment, with media, composition, and color. There are understated gestures that point to his early lessons in calligraphy, but these are works that suggest a willingness to try something new in every work.

It is an amazing story.

Kenjiro Nomura belongs on all of our lists of major artists. Thanks to David Martin and Barbara Johns, we can now see his paintings and learn his history. Kenjiro Nomura’s art work demonstrates his incredible ability as an artist and his perseverance as a human being.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com and for local, national, and international publications.

“Kenjiro Nomura American Modernist; An Issei Artist’s Journey” is on view through February 20 from Thursday through Sunday from 11 A.M. to 5 P.M. at Cascadia Art Museum, located at 190 Sunset Avenue South in Edmonds, Washington. For further information, visit www.cascadiaartmuseum.org.