You enter most museum exhibits a minute or two after you step through the museum’s front door. For the “Wood” exhibit at the Jefferson Museum of Art & History in Port Townsend, it’s different: this show starts with the front doors—they are part of the exhibit.

You enter most museum exhibits a minute or two after you step through the museum’s front door. For the “Wood” exhibit at the Jefferson Museum of Art & History in Port Townsend, it’s different: this show starts with the front doors—they are part of the exhibit.

The museum is rebuilding the structure’s original cedar doors after 130 years of service. A video in the lobby documents the crafting of the new construction. The experience puts you immediately in the right frame of mind to appreciate the world of “Wood.” The rebuild also hints at the broader changes underway at the museum, as its leadership reimagines the way it frames and presents local history.

The museum is rebuilding the structure’s original cedar doors after 130 years of service. A video in the lobby documents the crafting of the new construction. The experience puts you immediately in the right frame of mind to appreciate the world of “Wood.” The rebuild also hints at the broader changes underway at the museum, as its leadership reimagines the way it frames and presents local history.

“Wood” offers a cross-section of the region’s woodworking talents. It showcases furniture, sculpture, and tools, along with pieces that are more difficult to classify. With its focus on five artisans, the exhibition is balanced and admirably diversified. One of the featured artists is just starting out on her path, while some are in their mature master phase. Some of the artisans are well known and well shown in the region, while others keep a lower profile.

The range of the work on display is similarly diverse. Several pieces are all about function and utility—a rocking chair, a sheet music stand, a milking stool—while some works are fine art objects. All of them achieve beauty, and visitors may struggle with the standard museum admonition, “Do not touch.” But on that point, the curators have set out blocks of various woods for visitors to pick up, smell, and otherwise inspect, with descriptions of each wood’s characteristics from a woodworker’s perspective. These are especially worthwhile if the only wood you can reliably identify is particle board.

We begin with the pairing of Annalise Rubida, an emerging talent, and her mentor Steve Habersetzer, a traditional master craftsman. Both are affiliated with the Port Townsend School of Woodworking (PTSW). Both have a mind for the practical—their contributions are pieces of furniture, and tools or objects meant to do work. Rubida’s Windsor rocking chair is an impressive and ambitious piece. But her more modest creations are charming as well, such as her pair of hand-carved brooms (a long-handled push broom, and a whisk-broom). Tool users tend to be toolmakers—you get the sense that Rubida would never clean up wood shavings and sawdust with a Shop-Vac.

Habersetzer brings decades of experience with wood—he worked as a logger at one point, a ship-builder at another. He is something of a purist these days: he uses only hand-tools, and he works with locally sourced and sustainably harvested wood. Most of Habersetzer’s work in the show—such as the buckets made of cedar staves—embody simplicity and practicality. These values he now passes on to the next generation of craftspeople coming through PTSW.

Like Rubida and Habersetzer, Seth Rolland is a furniture-maker, but in his creations we see more emphasis on imagination and decoration. Scandinavian design aesthetics influence some of his work, and he likes to bring in materials such as stone and glass into his explorations of organic form. Several pieces by Rolland are entirely sculptural, such as “Ghost Tree,” with its display of wood bending. Note that he crafted “Ghost Tree” from a single piece of wood.

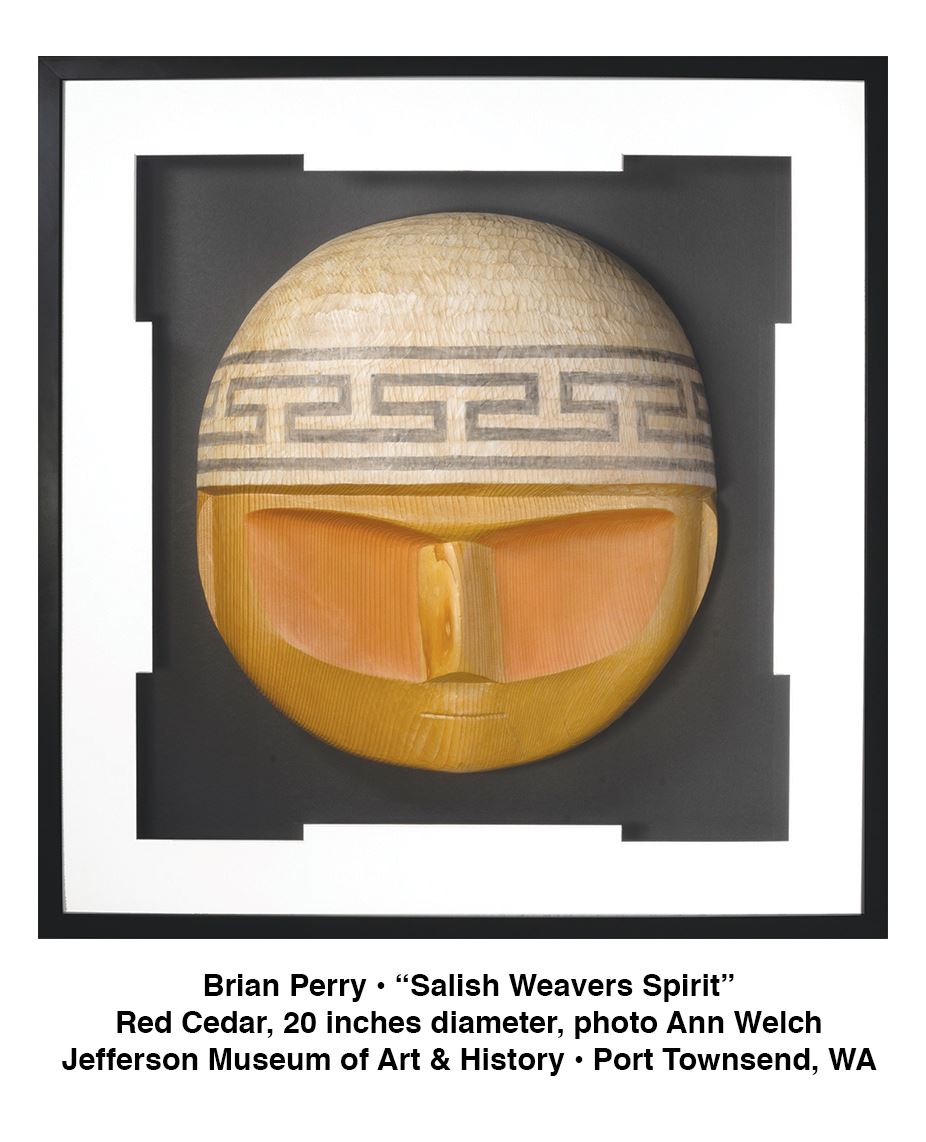

Next comes Brian Perry of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, a prominent wood carver. Some of his creations are in Seattle’s Burke Museum and in various public spaces on tribal land. He often works at large scale: story poles, totem poles, wall facades, canoes. “Wood” features Perry at a more intimate scale, including his powerful “Salish Weavers Spirit,” a carving that honors the art and craft of weaving. In Coastal Salish tradition, women do the weaving, men do the wood-carving. The women use non-representational design elements in their textiles; the men depict animal and human figures in their carvings. Perry’s “Salish Weavers Spirit” includes a geometric motif drawn from the weaving vocabulary, and its shape suggests the whorls that weavers use for the spinning process. One take on Perry’s carving (perhaps a naive take) is that it sees beyond divisions between art practices, between genders, between the human and the spiritual.

Next comes Brian Perry of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, a prominent wood carver. Some of his creations are in Seattle’s Burke Museum and in various public spaces on tribal land. He often works at large scale: story poles, totem poles, wall facades, canoes. “Wood” features Perry at a more intimate scale, including his powerful “Salish Weavers Spirit,” a carving that honors the art and craft of weaving. In Coastal Salish tradition, women do the weaving, men do the wood-carving. The women use non-representational design elements in their textiles; the men depict animal and human figures in their carvings. Perry’s “Salish Weavers Spirit” includes a geometric motif drawn from the weaving vocabulary, and its shape suggests the whorls that weavers use for the spinning process. One take on Perry’s carving (perhaps a naive take) is that it sees beyond divisions between art practices, between genders, between the human and the spiritual.

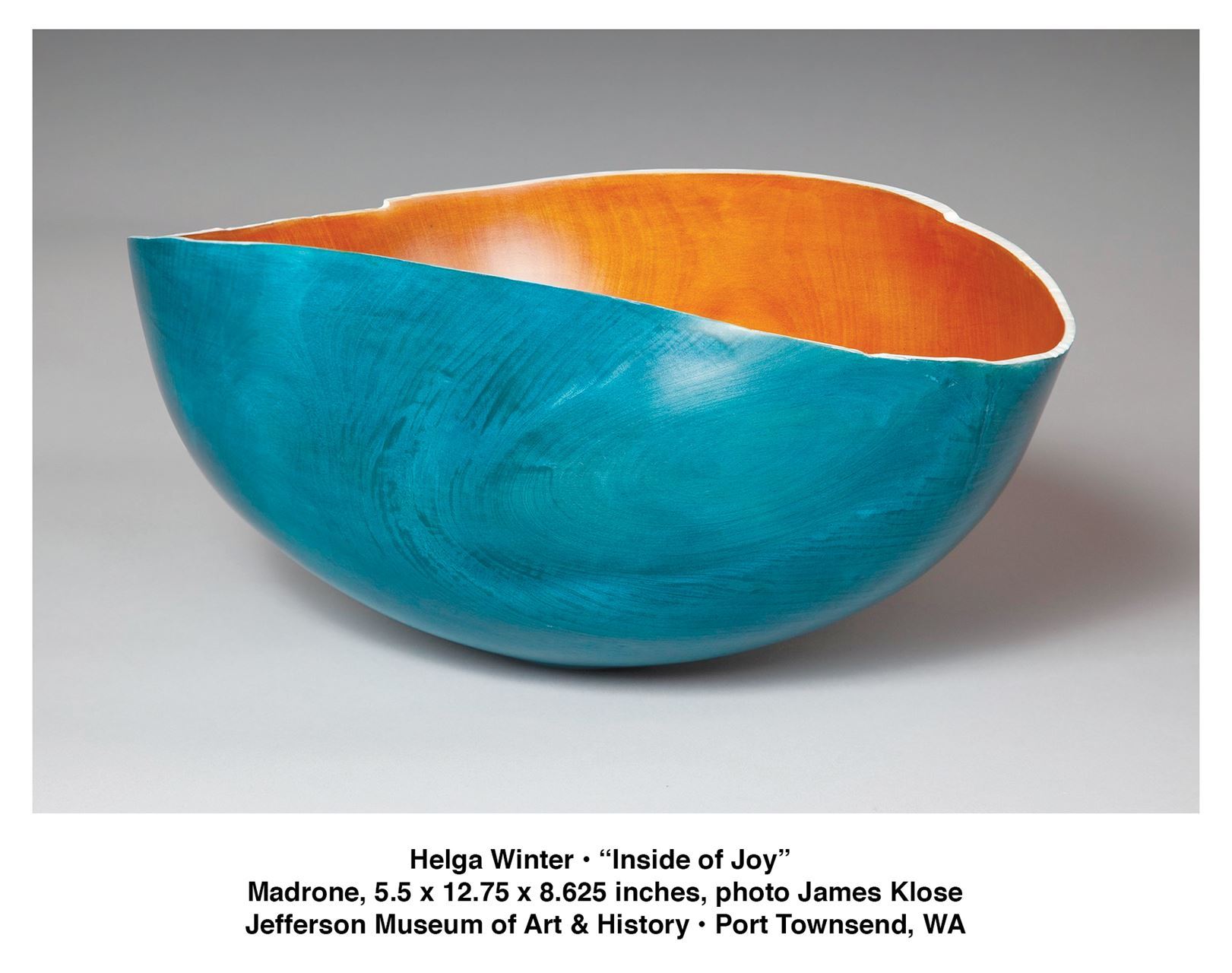

The exhibition continues into and concludes below the main level in a room that was once the women’s jail. In this captivating context we find turned-wood objects by Helga Winter. The irony is that Winter is the freest of the five artisans in “Wood”—her elegantly imperfect and asymmetric vessels are free from functional considerations, and are unconstrained by age-old tradition. Even the wood she favors—Pacific madrone—reflects her free-spirit: the hardwood is notoriously unpredictable in response to cutting. It is prone to warping and even cracking, but Winter embraces that waywardness. She often decorates her surfaces with color and abstract design—sometimes using busy marks and dotted patterns, other times using thin washes of solid color that keep the wood grain visible while glowing with a presence of their own.

Rounding things out, “Wood” includes photographer Jeremy Johnson’s large format black-and-white portraits of the show’s five artists, and a display of the hand tools used by 19th century home-builder A. Horace Tucker. Tucker constructed some of Port Townsend’s most iconic homes, including the Pink House, Captain Fowler’s House, and the 1868 Rothschild House. His work literally looms large over the town, and may even have something to do with the vitality of the woodworking scene that “Wood” celebrates.

Tom McDonald

Tom McDonald is a writer and musician living on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

Jefferson Museum of Art & History (540 Water Street in Port Townsend, Washington) is open Thursday to Sunday from 11 A.M. to 4 P.M. “Wood”is on view through May. Visit www.jchsmuseum.com for information.