This summer and into the fall, Bainbridge Island Museum of Art is putting on a retrospective of works by the celebrated Northwest visionary, George Tsutakawa (1910-1997). Maybe “Northwest visionary” doesn’t quite do the artist justice: Tsutakawa attained international stature in his time, rivaling that of his friends Mark Tobey and Morris Graves. With over seventy artworks on hand—paintings, drawings, sculptures, hand-crafted furniture—as well as a gorgeous exhibition catalogue, the retrospective is a real occasion.

This summer and into the fall, Bainbridge Island Museum of Art is putting on a retrospective of works by the celebrated Northwest visionary, George Tsutakawa (1910-1997). Maybe “Northwest visionary” doesn’t quite do the artist justice: Tsutakawa attained international stature in his time, rivaling that of his friends Mark Tobey and Morris Graves. With over seventy artworks on hand—paintings, drawings, sculptures, hand-crafted furniture—as well as a gorgeous exhibition catalogue, the retrospective is a real occasion.

People often asked George Tsutakawa if he was Japanese or American, and he liked to answer “both.” His commitment to both, his ability to unify them, is part of what makes the artist loom large in the post-WWII arts scene. Born in Seattle in 1910, Tsutakawa was sent to Japan in early childhood, receiving a rich education in traditional Japanese arts and culture. His well-off family charted out his educational future, but Tsutakawa rejected it, particularly its militarist aspect. Disowned, Tsutakawa came back to Seattle. At University of Washington, he studied art and philosophy while working in fish canneries and produce stands to support himself.

People often asked George Tsutakawa if he was Japanese or American, and he liked to answer “both.” His commitment to both, his ability to unify them, is part of what makes the artist loom large in the post-WWII arts scene. Born in Seattle in 1910, Tsutakawa was sent to Japan in early childhood, receiving a rich education in traditional Japanese arts and culture. His well-off family charted out his educational future, but Tsutakawa rejected it, particularly its militarist aspect. Disowned, Tsutakawa came back to Seattle. At University of Washington, he studied art and philosophy while working in fish canneries and produce stands to support himself.

The horrors of WWII and a climate of racial hatred caused many Japanese Americans living in the U.S. to distance themselves from their Japanese heritage, and this was true of Tsutakawa. He poured himself into European and American culture and embraced modernism in all its forms. But a cultural shift was going around him. Local painters like Morris Graves and Mark Tobey, writers like Gary Snyder, musicians like John Cage (then teaching at Cornish), had all been moving in an opposite direction: they disdained many aspects of “Western” culture and found artistic and spiritual inspiration in Zen and other “Eastern’’ practices. Tsutakawa was well-suited to flourish in those cultural cross-currents.

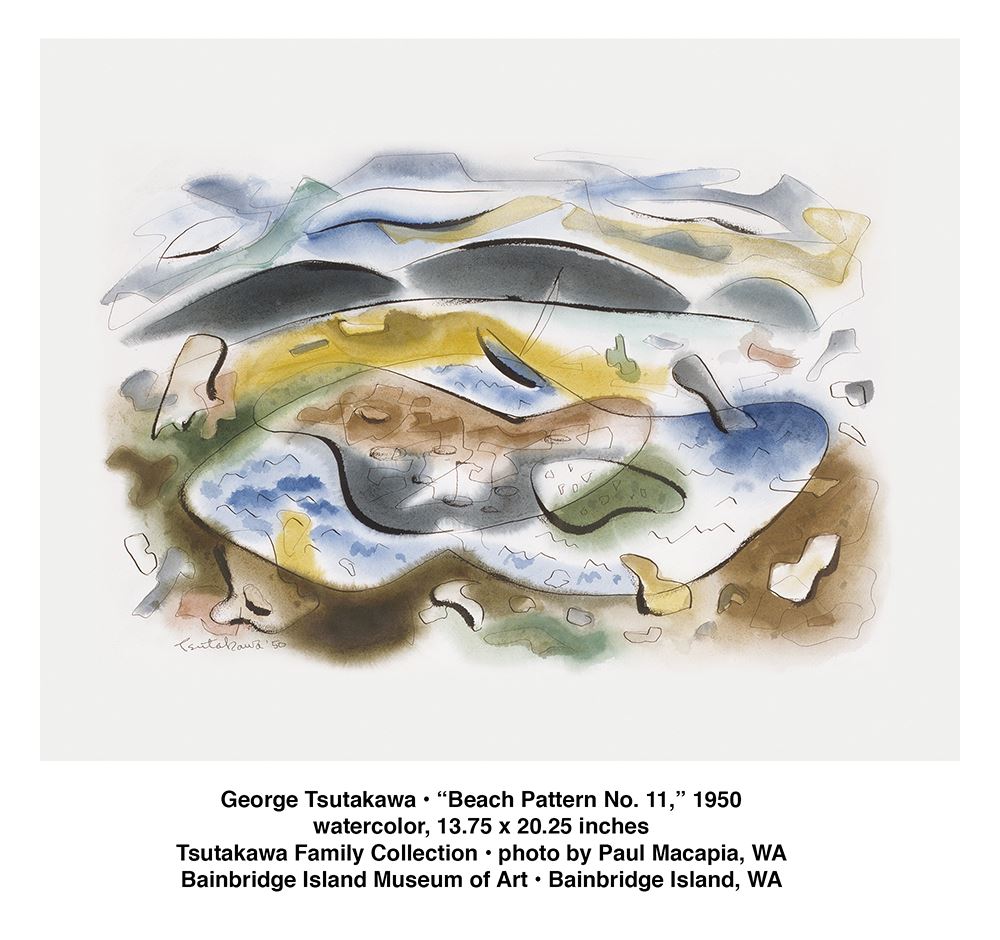

The retrospective concentrates on his work from the 1950s forward. One of the earliest pieces on view is “Beach Pattern No. 11” (1950). Tsutakawa’s reverence for water is already present in the work. While the watercolor reveals traces of his later style, what leaps out more strongly is the influence of Cubism and Expressionism.

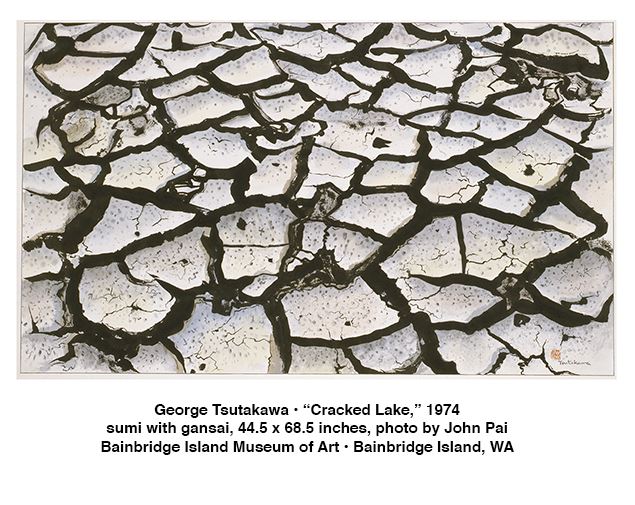

Encouraged by Mark Tobey, Tsutakawa began to revive his connection to the Japanese aesthetics he’d once renounced. You can see this evolution in works from the 1960s and beyond. One highlight of the show is “Cracked Lake” from 1974. The large painting in sumi and gansai (Japanese watercolor) plays a game of making ink and paper look like clay. It’s the clay of a dried-up lake-bed that Tsutakawa represents, but this image echoes the ceramic style most prized in Japan during Tsutakawa’s childhood: Hagi ware. Rawness and simplicity characterizes the style, as does the unpredictable web of cracks in the glaze.

What is also striking about “Cracked Lake” is what’s absent from it: water and life. Other paintings from the same period teem with living creatures. It’s as if “Cracked Lake” invites a meditation on impermanence.

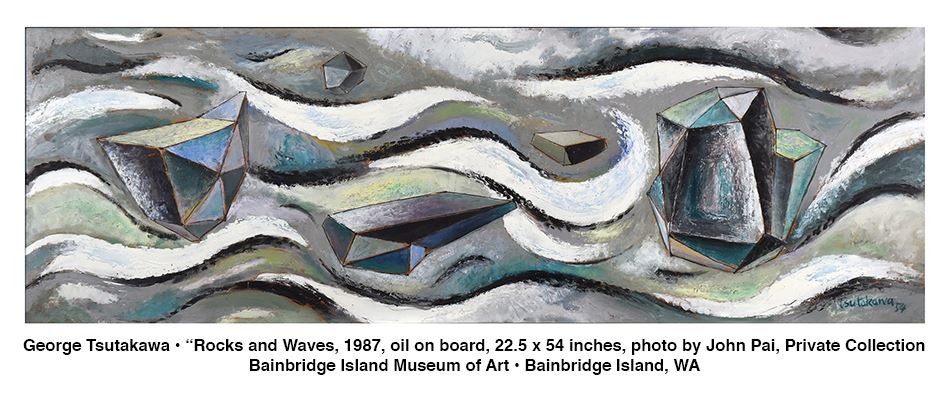

As fine as the paintings may be, Tsutakawa made his greatest marks with wood and bronze sculptures. One major inspiration for Tsutakawa’s new directions in sculpture came from reading the 1952 travelog, “Beyond the High Himalayas.” Its author, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas described obos, stacked rock formations erected by pilgrims traversing mountain passes, each traveler adding their own stone or flat boulder to the monument. Whatever import the artist found here, obos entranced him enough that they began turning up in his paintings (“Flying Obos”). In ‘57 he set out to explore these humble forms in a series of wooden sculptures. For these works Tsutakawa chose teak, a wood that is native to India and Southern Asia. This show includes several pieces from the series, some in wood, some in bronze.

As fine as the paintings may be, Tsutakawa made his greatest marks with wood and bronze sculptures. One major inspiration for Tsutakawa’s new directions in sculpture came from reading the 1952 travelog, “Beyond the High Himalayas.” Its author, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas described obos, stacked rock formations erected by pilgrims traversing mountain passes, each traveler adding their own stone or flat boulder to the monument. Whatever import the artist found here, obos entranced him enough that they began turning up in his paintings (“Flying Obos”). In ‘57 he set out to explore these humble forms in a series of wooden sculptures. For these works Tsutakawa chose teak, a wood that is native to India and Southern Asia. This show includes several pieces from the series, some in wood, some in bronze.

Tsutakawa made his breakthrough bronze fountain sculpture in 1960; “Fountain of Wisdom” was based on the obos concept. The piece was commissioned for the entrance to the Seattle Public Library—the artist’s first major public art commission (two more commissions came before the first was even unveiled). This exhibition includes select proposal drawings and models (maquettes) depicting several of his towering fountains; the exhibition catalog includes several photographs of the actual works installed at sites all over the world.

The obsession with the obos didn’t end there for Tsutakawa, however. At the age of 67 he climbed to the 15,000-foot level in the Himalayas to see obos with his own eyes. This story comes up in the exhibition catalog, and it speaks volumes about Tsutakawa’s life.

Maybe it is that larger-than-life quality that inspired Bainbridge Island Museum to install a tribute to the artist in the museum’s two-story window gallery. For this effort, the curatorial and installation teams collaborated with artist June Sekiguchi and artist/engineer Charles Faddis. It’s a fitting gesture for a towering figure like Tsutakawa.

Tom McDonald

Tom McDonald is a writer and musician living on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

“George Tsutakawa: Language the Nature” is on view at Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, located at 550 Winslow Way on Bainbridge Island, Washington, and open daily from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. For more information, visit www.biartmuseum.org.