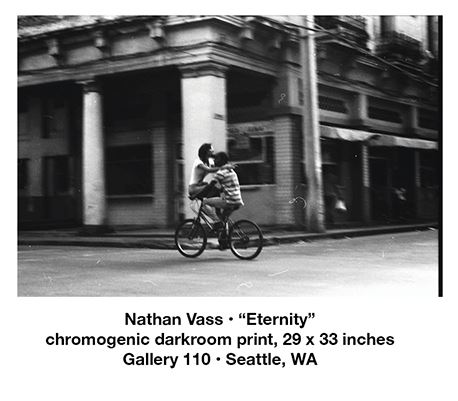

In Nathan Vass’ July exhibition at Gallery 110, a black and white image of a couple on a bicycle in Havana stands out among strangely-colored, multi-layered landscape photographs. Framed by the white corner column of a building, the woman balances on handle bars, her arms encircling his shoulders, chin visually joined to his brow. In the split-second captured on 35mm film, the couple is frozen, intimate and joyous, caught between a blurred past and future, time bifurcated by the white of the framing column. Entitled “Eternity,” the photograph captures the essence of this show titled “Present Perfect,” referencing the verb tense used for a past that is not yet gone, which still affects, still is active in, the present.

In Nathan Vass’ July exhibition at Gallery 110, a black and white image of a couple on a bicycle in Havana stands out among strangely-colored, multi-layered landscape photographs. Framed by the white corner column of a building, the woman balances on handle bars, her arms encircling his shoulders, chin visually joined to his brow. In the split-second captured on 35mm film, the couple is frozen, intimate and joyous, caught between a blurred past and future, time bifurcated by the white of the framing column. Entitled “Eternity,” the photograph captures the essence of this show titled “Present Perfect,” referencing the verb tense used for a past that is not yet gone, which still affects, still is active in, the present.

Vass has become well-known as a writer and speaker following his bestselling 2019 book, The Lines That Make Us: Stories from Nathan’s Bus, on his experiences as Seattle’s friendliest Metro driver. Vass, like “Eternity,” is joyous in conversation, extolling the unique benefit that comes from talking to strangers, chit-chat that creates a singular moment of connection with society as a whole. Here, however, in these photographs, he is leaning into the emotional interface between his public and private self: art making as a processing of subjective reaction to external experience; photography not as a means to reproduce what something looks like, but rather what it feels like. He is leaning into memory.

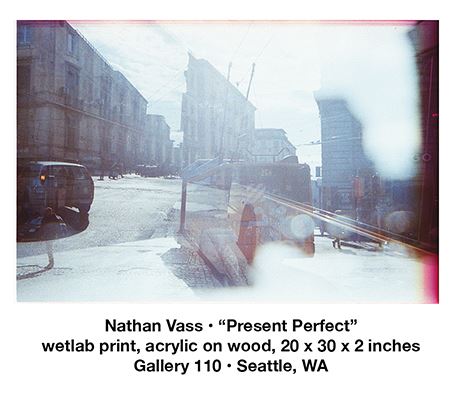

Most of the images in this show originate in what in other hands would be ersatz tourist postcards, authentications of Kilroy’s presence in a famous place. Vass transforms these into authentications of emotional experience, sometimes layering images in the camera itself (as un-advanced film) — “Dreams of Seoul” looks simultaneously down on the city and up at the clouds above, lights of the city at night burning like constellations in the long slow shot, moving lights tracing worm patterns in the winter sky, out-of-focus overlay splotching the surface like water stains — or by cross-processing the film (developing 35mm slide film in a chemical bath for color negatives) to shift color and intensify contrast, adjusting not for “objective” accuracy but for emotional truth.

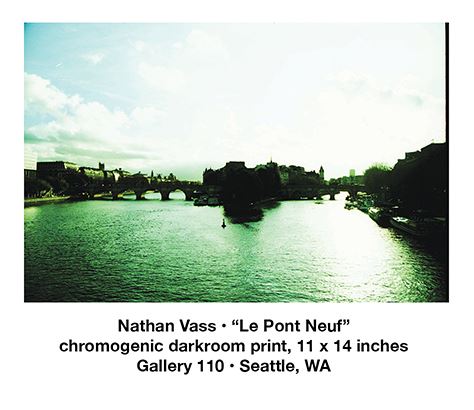

Vass took “Le Pont Neuf” in the days following the 2015 terrorist attacks that targeted multiple sites around Paris, killing 137 and injuring over 416. Cross-processed, the color is intense and bilious green, the contrast high. The warm black of the central image absorbs like a black hole: an afterimage burned into a retina. The stillness and shock permeating the city are palpable.

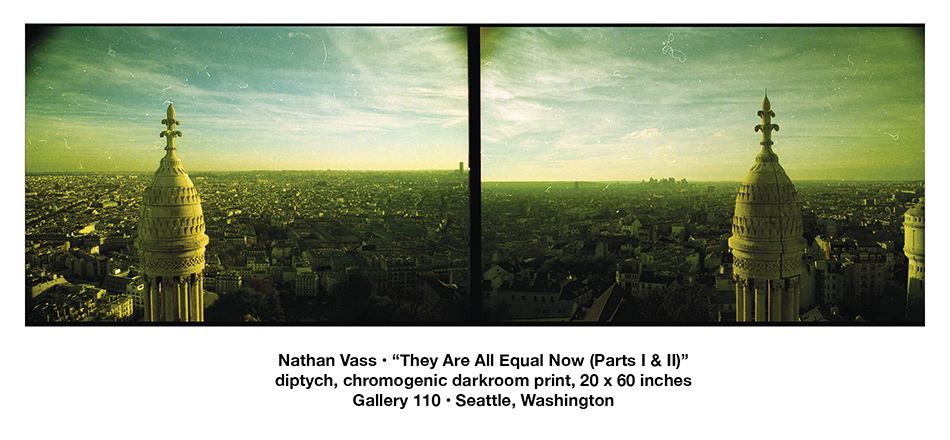

A diptych, “They Are All Equal Now (Parts I & II)” likewise captures the scope of the attacks. Taken facing south and east from an observation tower at Sacré-Coeur overlooking Paris and overlaid with yellow and blue filters, the image documents the uncanny: the stillness of the city laden with the vast commonality of death.

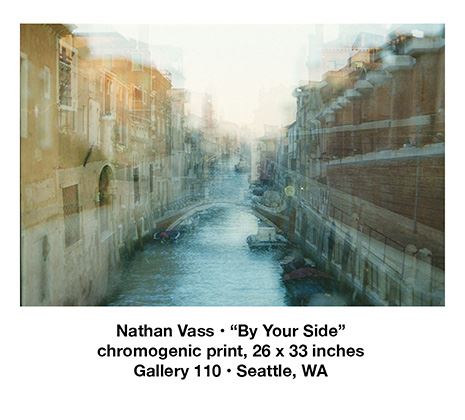

Death and eternity are present too in “By Your Side.” Triple images of a canal in Venice—the canal with a distant bridge overlaid with telephoto close-up of the bridge, combined with an out-of-focus shot of the same scene—create a sense of vertigo, an instability, an unmooring. There is a timelessness here, of immanent change: acute nostalgia for past, present, and uncertain future.

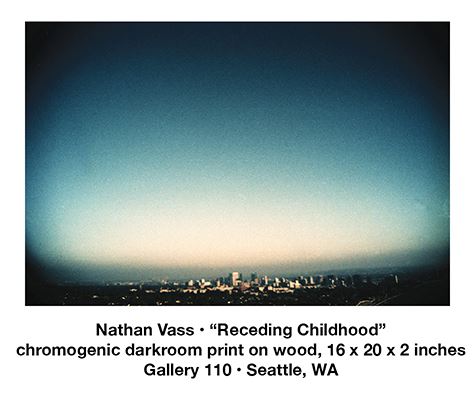

For “Receding Childhood,” Vass photographed L.A. with discontinued Velvia slide film, then cross-processed and mounted the image on wood. Blurry and distant as if viewed through the wrong end of a telescope, rounded by black from a camera too small for the film, the city is dwarfed by the vividly blue desert sky suspended over it like a vast, neon egg.

Photography is an art of memory, the touch of light bouncing from image to transform the surface of the film, then bouncing from image to the eye; as Susan Sontag noted, in beholding a photograph, we are touched by the past itself; as Roland Barthes noted, in looking at a photograph of a person, we are witness to their present existence, as well as their future and present deaths.These are complicated tenses: past, present, and past together. Or this is how we have reflected on photography in the past. In the present, film photography is itself becoming a relic, overwritten by the revolution present in the digital camera in every smartphone.

Vass, graduate of the last University of Washington School of Art class trained in color darkroom processing, is acutely cognizant of working in a disappearing medium. But this is what he is leaning into in these images: into the interface between objective and subjective authenticity; into the practice of memory in a process that is becoming memory itself; into the authenticity of his own present perfect.

Vass, graduate of the last University of Washington School of Art class trained in color darkroom processing, is acutely cognizant of working in a disappearing medium. But this is what he is leaning into in these images: into the interface between objective and subjective authenticity; into the practice of memory in a process that is becoming memory itself; into the authenticity of his own present perfect.

Elizabeth Bryant

Elizabeth Bryant is an art writer.

“Present Perfect” is on view Thursday through Saturday from noon to 5 P.M. at Gallery 110, located at 110 Third Avenue South in Seattle, Washington. For more information, visit www.gallery110.com.