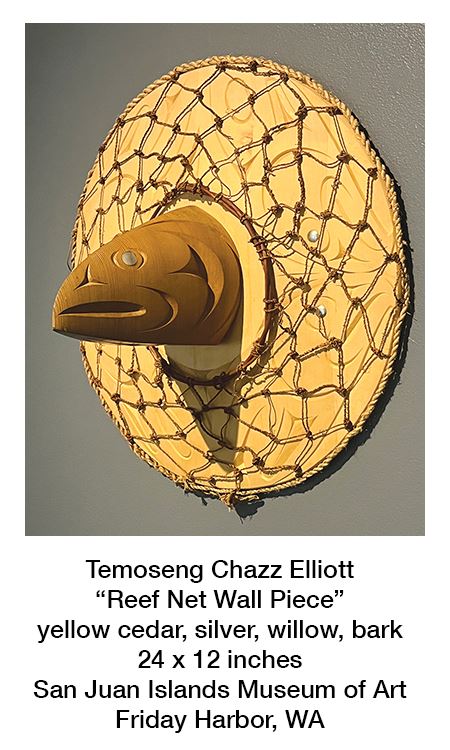

A salmon peers from the circular opening of a bark net, graceful, silver-eyed shapes of four more on the cedar disc beneath. Carved by a First Nations artist, the piece represents an ancient culture of conservation—an effort not to exhaust the vital resources of the land and sea. Temoseng Chazz Elliott’s carving forms a counterpoint in this cross-border art exhibition, much of which interrogates the contemporary culture of consumption.

A salmon peers from the circular opening of a bark net, graceful, silver-eyed shapes of four more on the cedar disc beneath. Carved by a First Nations artist, the piece represents an ancient culture of conservation—an effort not to exhaust the vital resources of the land and sea. Temoseng Chazz Elliott’s carving forms a counterpoint in this cross-border art exhibition, much of which interrogates the contemporary culture of consumption.

“Archipelago—Contemporary Art of the Salish Sea: Southern Gulf Islands Artists,” is the second half of a project by the San Juan Islands Museum of Art (SJIMA) working with British Columbia’s ArtSpring and Salt Spring Arts galleries. SJIMA exhibited six San Juan Island artists this summer and now is showing six artists from Canada’s Southern Gulf Islands, questioning the influence of environment on the art of a region. The current show is beautiful, even profound, although whether a common environment evokes a common artistic response remains unanswered.

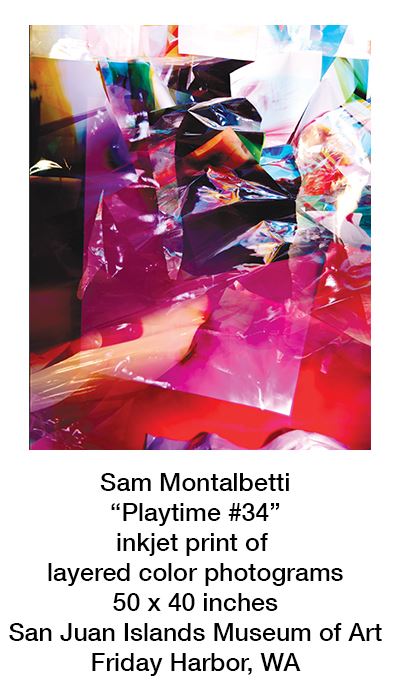

Elliott, a Tsawout artist, expresses intimacy with a territory inhabited by his ancestors for millenia. Made with traditional materials and techniques, his elegant, pristine carvings are deeply rooted in the environment. In contrast, Sam Montalbetti, born and raised on Salt Spring Island, creates work that has little to do with the Salish Sea. Concerned with the extinction of analog color photography, he turns his focus from the outside world to paint with light directly on sensitized paper, printing, cutting, layering, re-shooting to build brilliantly-colored abstractions: playful visual jazz. For another series, he tosses water into a night sky to capture motes of dust, tiny orbs suggesting galaxies infinitely larger and smaller than the visible world. This is the environment to which he responds, creating new possibilities from old technology.

Elliott, a Tsawout artist, expresses intimacy with a territory inhabited by his ancestors for millenia. Made with traditional materials and techniques, his elegant, pristine carvings are deeply rooted in the environment. In contrast, Sam Montalbetti, born and raised on Salt Spring Island, creates work that has little to do with the Salish Sea. Concerned with the extinction of analog color photography, he turns his focus from the outside world to paint with light directly on sensitized paper, printing, cutting, layering, re-shooting to build brilliantly-colored abstractions: playful visual jazz. For another series, he tosses water into a night sky to capture motes of dust, tiny orbs suggesting galaxies infinitely larger and smaller than the visible world. This is the environment to which he responds, creating new possibilities from old technology.

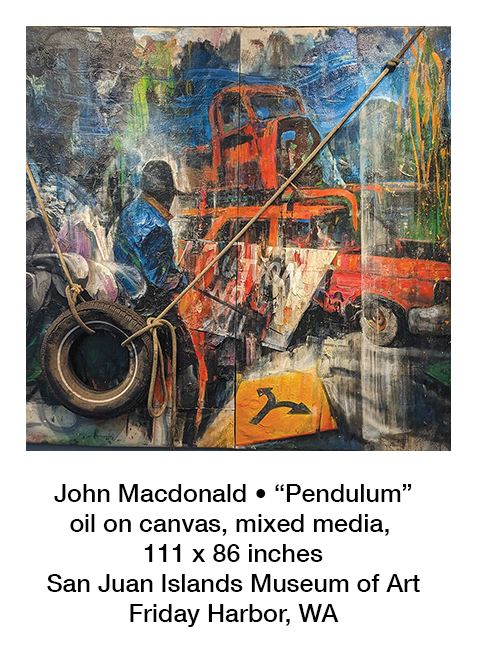

John Macdonald’s large-scale paintings are drawn from personal interests and experience; though painterly and abstracted, they maintain an illustrative narrative. In front of a flame-colored truck, a hanging tire quotes Rauschenberg; road signs signal “Caution” and a choice of left or right: there is politics, and a world on fire. Tagged by numbers, deer in maple move through slanting shafts of color, their wildness belied by the artificial system in which they are caught. A figure lost in a snowy forest is painted on salvaged scrap wood, the far-left roof-tar black; high on the right, a single light bulb; on the left, an eagle shape of twigs mounted on scrap metal, the head a cast of white. This is Macdonald’s most personal painting, referencing a palpable loss.

John Macdonald’s large-scale paintings are drawn from personal interests and experience; though painterly and abstracted, they maintain an illustrative narrative. In front of a flame-colored truck, a hanging tire quotes Rauschenberg; road signs signal “Caution” and a choice of left or right: there is politics, and a world on fire. Tagged by numbers, deer in maple move through slanting shafts of color, their wildness belied by the artificial system in which they are caught. A figure lost in a snowy forest is painted on salvaged scrap wood, the far-left roof-tar black; high on the right, a single light bulb; on the left, an eagle shape of twigs mounted on scrap metal, the head a cast of white. This is Macdonald’s most personal painting, referencing a palpable loss.

The three women artists use sewing, stitching, weaving in their art. Perhaps a result of long meditative hours of handwork, here we find a complete response to environment of the Salish Sea in both overt and hidden manifestations.

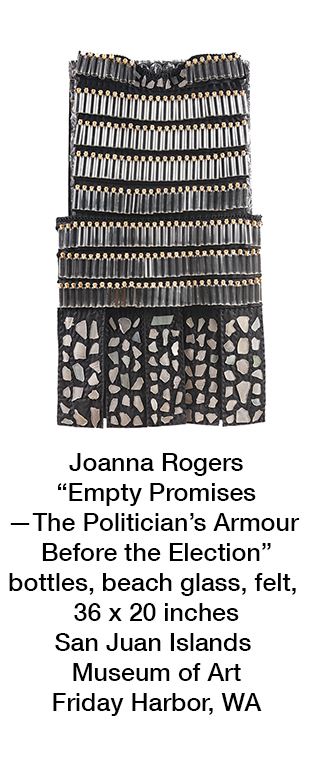

Joanna Rogers stitches leaves, shells, plastic bread ties, small empty bottles, beach glass onto felt forms taken from the shape of Joan of Arc’s armor. Although given European sources, in this show, adorned with Salt Spring Island artifacts, her work seems to refer to First Nations culture: Haida warrior armor; button blankets; dance capes: native resources exploited by colonization; nature supplanted by plastic. Her most ambitious work is an elegant series of naturally-dyed scarfs into which a line from a poem is woven in Morse code. Entirely of texture, each coded message, she explains, is a last cry from a dying species—a lament for remembrance: subtlety decoded only with close attention.

Joanna Rogers stitches leaves, shells, plastic bread ties, small empty bottles, beach glass onto felt forms taken from the shape of Joan of Arc’s armor. Although given European sources, in this show, adorned with Salt Spring Island artifacts, her work seems to refer to First Nations culture: Haida warrior armor; button blankets; dance capes: native resources exploited by colonization; nature supplanted by plastic. Her most ambitious work is an elegant series of naturally-dyed scarfs into which a line from a poem is woven in Morse code. Entirely of texture, each coded message, she explains, is a last cry from a dying species—a lament for remembrance: subtlety decoded only with close attention.

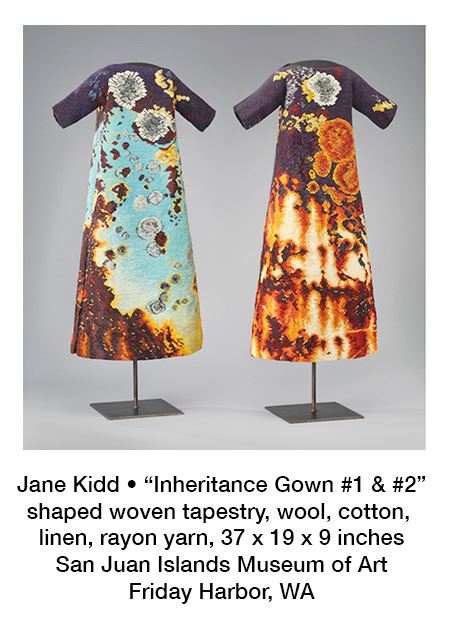

Jane Kidd’s exquisite tapestries also require close attention, though her concern for the environment is overt. A shawl-like garment hangs folded-over: on top, a fish-kill below streaks of rain; obscured beneath, industrial smokestacks spew clouds of pollution. Four tapestries draped as garments maintain a human form, each worked in gorgeous color and pattern, each a site of environmental disaster: tar sand; pit mine; deforestation; desertification. Two small gowns, dyed with rust, represent our children’s inheritance: lichen-like patterns like the regeneration of organic life from barren rock or fallout from environmental apocalypse: hope or decay? These are tapestries as masterworks.

Jane Kidd’s exquisite tapestries also require close attention, though her concern for the environment is overt. A shawl-like garment hangs folded-over: on top, a fish-kill below streaks of rain; obscured beneath, industrial smokestacks spew clouds of pollution. Four tapestries draped as garments maintain a human form, each worked in gorgeous color and pattern, each a site of environmental disaster: tar sand; pit mine; deforestation; desertification. Two small gowns, dyed with rust, represent our children’s inheritance: lichen-like patterns like the regeneration of organic life from barren rock or fallout from environmental apocalypse: hope or decay? These are tapestries as masterworks.

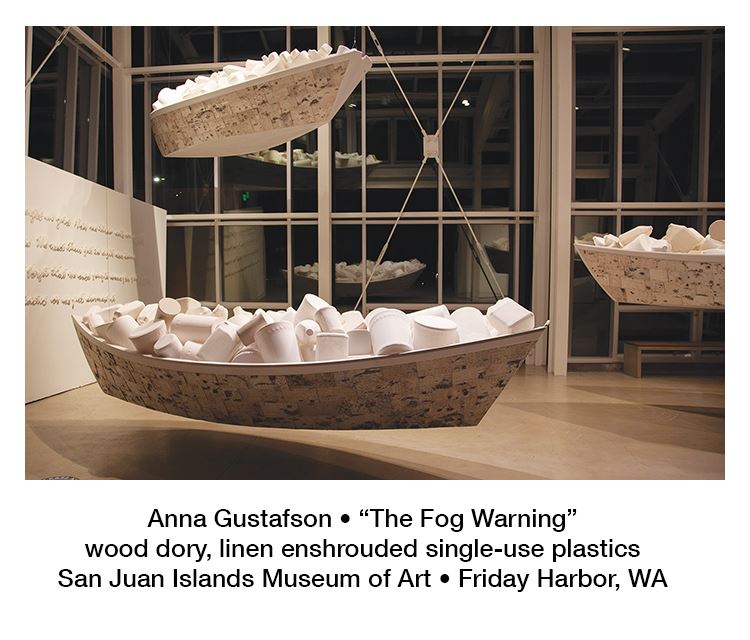

The highlight of the exhibition is an installation by Anna Gustafson: Three birch-bark dories filled with jugs of single-use plastic wrapped in white linen are suspended in the front glassed-in exhibition space. In a small alcove, a seine net suspends another catch of enshrouded plastic over a baby grand piano. What is our cultural legacy? Gustafson’s installation is a direct reply to Elliott’s concern: soulless empty vessels replace depleted salmon runs. On the walls, messages are written in salt-encrusted twine threaded with steel wire like white neon: “Salt. Whale. Oil.”

In the past, she says, salt and whale oil were key to our economy; may our dependence on oil become as obsolete. This is our hope.

Elizabeth Bryant

Elizabeth Bryant

Elizabeth Bryant is an art writer and English/ESL tutor.

“Archipelago—Contemporary Art of the Salish Sea” is on view Friday through Monday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. until December 4 at the San Juan Islands Museum of Art, located at 540 Spring Street in Friday Harbor, Washington. Visit www.sjima.org for more information.