Ethereal & Tangible Art

Bainbridge Arts & Crafts • Bainbridge Island, Washington

Coming off its 75th anniversary late last year, Bainbridge Arts & Crafts continues the excitement with a show of two intriguing regional artists: painter Christian Carlson (Mount Vernon) and sculptor David Eisenhour (Port Hadlock).

Coming off its 75th anniversary late last year, Bainbridge Arts & Crafts continues the excitement with a show of two intriguing regional artists: painter Christian Carlson (Mount Vernon) and sculptor David Eisenhour (Port Hadlock).

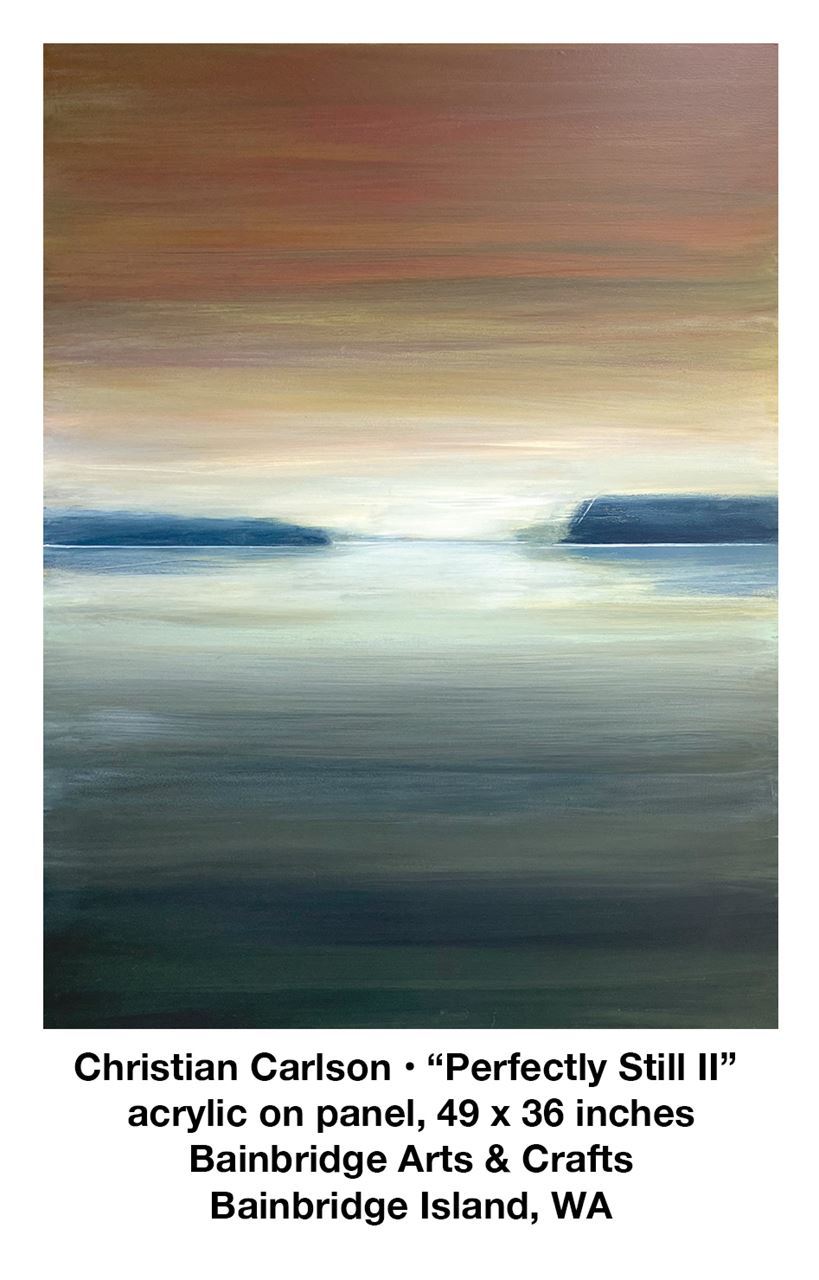

Carlson is a relatively recent arrival to the Skagit Valley, a place that has long produced and attracted landscape painters inspired by the region’s natural beauty. Carlson’s spacious coastal scenes are meditative and luminous; they can seem gently severe or pleasantly serene as your own perceptions of them evolve.

In “Winter Light,” as in so many of his paintings, islands or spits of land occupy the middle distance—dark backlit forms that straddle the horizon line. Behind them are misty headlands, while in the foreground sits a body of water rich in reflection, undulations, shallows and depths. A diffused light from an overcast sky softens the scene before you. But this painter is not out to capture the scene and call it good—he transfigures the setting in novel ways.

For decades Carlson favored conceptual art and abstract expressionism. Only with his move to Mount Vernon in 2017 did a representational approach take hold. An abstract-expressionist spirit is present the work: stark contrasts, dynamic interplay of shapes, gestural marks, and reduction of detail—these echo New York School artists, or point even farther back to Tonalist painters and their search for essence. Carlson simplifies his landforms by rounding them off, eliminating the coniferous forests that so define this region. He excludes boats, buoys, pilings—only the natural world belongs. Even wildlife is erased, as Carlson pares down to the elemental. By these means he distances his work from the Salish Sea; his islands and peninsulas become foreign, only vaguely familiar. Carlson’s not painting a place but letting the act of painting take him places. As he himself writes: “With tenacity [artists] will eventually find themselves in uncharted territory and this is the point!”

For decades Carlson favored conceptual art and abstract expressionism. Only with his move to Mount Vernon in 2017 did a representational approach take hold. An abstract-expressionist spirit is present the work: stark contrasts, dynamic interplay of shapes, gestural marks, and reduction of detail—these echo New York School artists, or point even farther back to Tonalist painters and their search for essence. Carlson simplifies his landforms by rounding them off, eliminating the coniferous forests that so define this region. He excludes boats, buoys, pilings—only the natural world belongs. Even wildlife is erased, as Carlson pares down to the elemental. By these means he distances his work from the Salish Sea; his islands and peninsulas become foreign, only vaguely familiar. Carlson’s not painting a place but letting the act of painting take him places. As he himself writes: “With tenacity [artists] will eventually find themselves in uncharted territory and this is the point!”

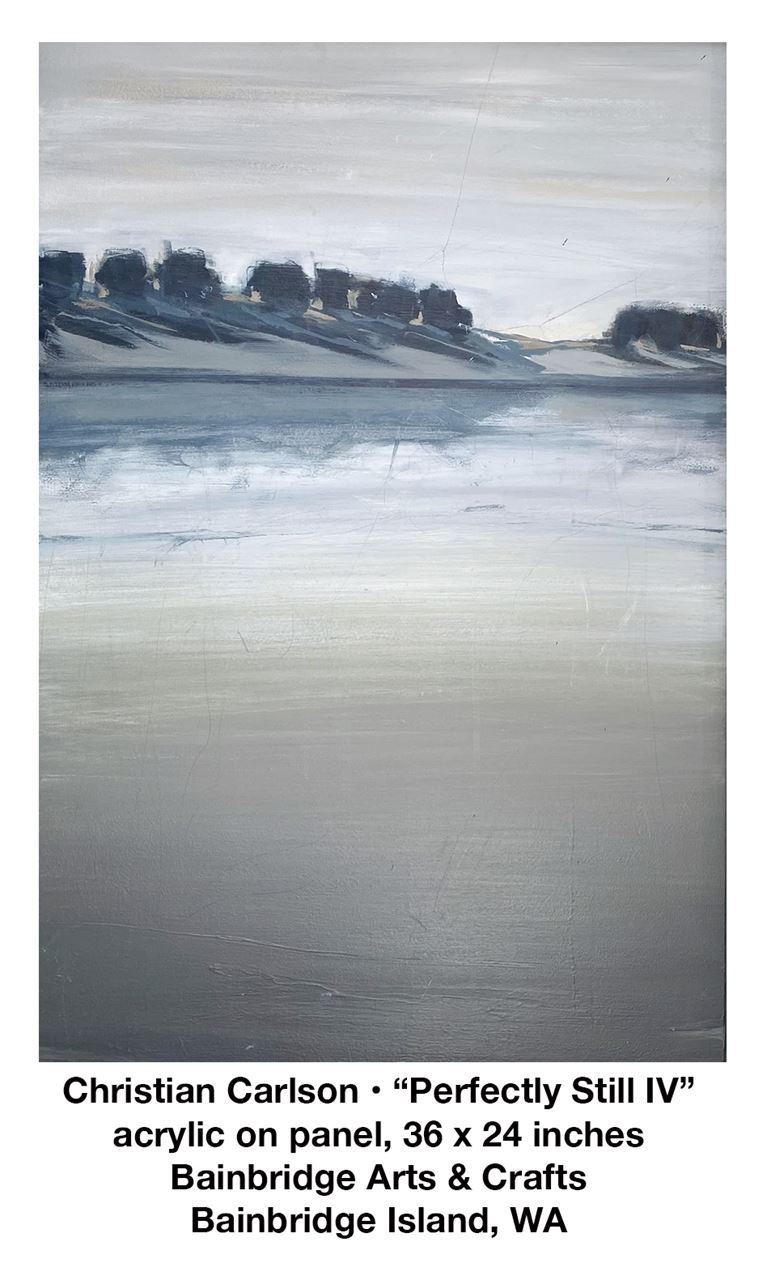

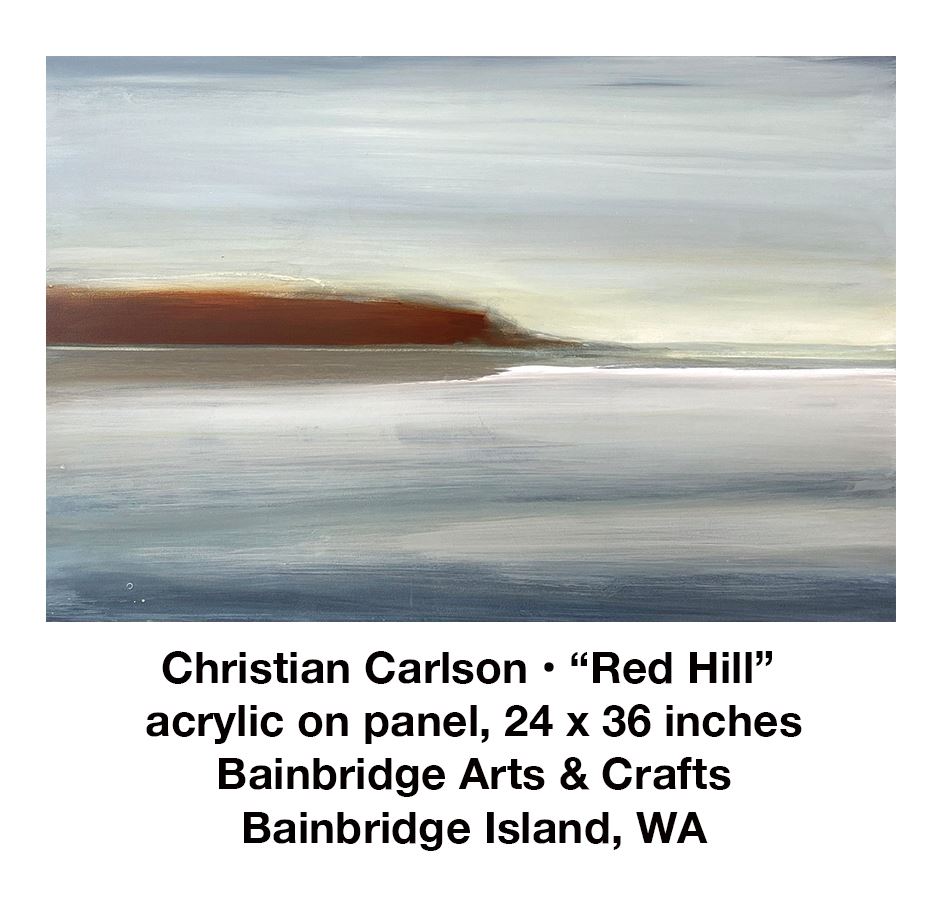

A subtle but important part of Carlson’s pursuit is to render realistic detail. A thin stroke of white describes a wave beginning to crest (“Red Hill”); a smudge of raw sienna defines a distant bluff. These touches seem to arise spontaneously from Carlson’s fluid, unfussy brushwork, but they anchor the mood and atmosphere to the specific. As if to counter these moves he will draw a graphite pencil along the painted surface, leaving hairlines that read, at first, as cracks in the paint (“Perfectly Still IV”). Their presence snaps you out of the immersive illusory space and back into the present moment.

In one way Carlson heightens the drama inherent in coastal settings; then again his formal simplicity evokes serenity. Working with muted colors and a limited palette, he depicts calm waters and placid skies captured at the most tranquil moments of the day. Even his titles are action-free: “Winter Light.” “Red Hill.” “Perfectly Still.”

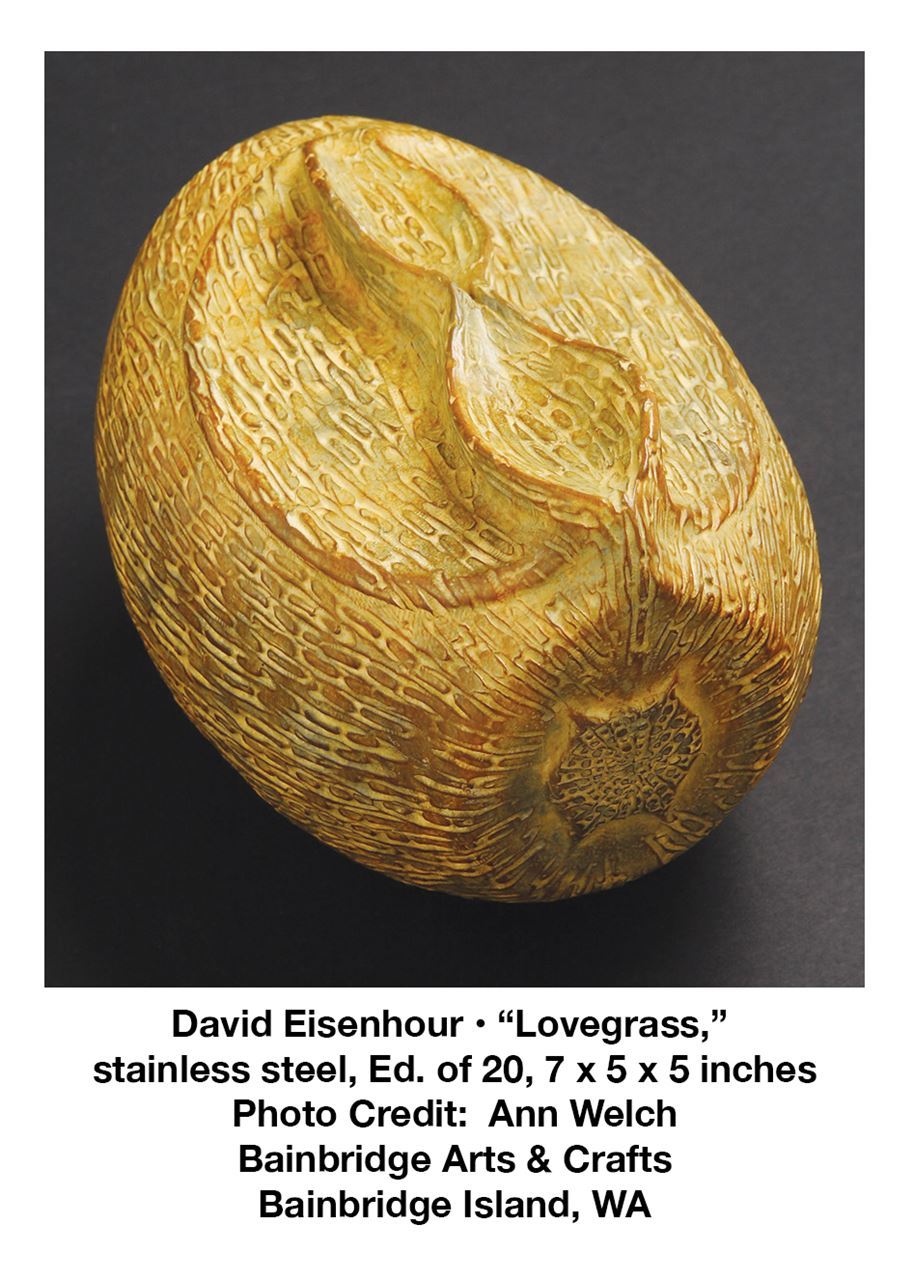

If Carlson tends toward the ethereal, the sculptor David Eisenhour is all about the tangible, usually in the form of bronze and stainless steel. Life-forms are mostly absent from Carlson’s work, but in Eisenhour’s there is nothing but the life-form—his commitment to the theme is total.

His fascination is often focused on miniscule organisms that we rarely see in life or in media. Eisenhour is entranced, too, by the patterns that creatures manifest: the precise spirals in mollusk shells, the radial symmetry of jellyfish. This aim is not only to perceive and to praise these wonders but to advocate for their protection. There’s some poetic irony in the fact that the fragile creatures Eisenhour offers up are cast in bronze and stainless steel—heavy-duty materials created under industrial-strength conditions.

His fascination is often focused on miniscule organisms that we rarely see in life or in media. Eisenhour is entranced, too, by the patterns that creatures manifest: the precise spirals in mollusk shells, the radial symmetry of jellyfish. This aim is not only to perceive and to praise these wonders but to advocate for their protection. There’s some poetic irony in the fact that the fragile creatures Eisenhour offers up are cast in bronze and stainless steel—heavy-duty materials created under industrial-strength conditions.

Eisenhour moved to the Puget Sound in 1992 to join the legendary Riverdog Foundry in Chimicum. There at the Northwest’s first bronze casting facility he learned all phases of the casting process; he assisted such prominent sculptors as Tony Angell, Phillip McCracken, and Phillip Levine, bringing their visions to final form. Eisenhour left the foundry to pursue his own creative work in 2003.

Though Eisenhour knows how to work a bronze furnace, his process really begins with a dissecting microscope. A life-long appreciator of minutia, Eisenhour magnifies his findings for all to admire. “Lovegrass” is a single seed of grain that you’d need a micrometer to measure, but here it’s magnified to pumpkin-size and transmuted into stainless steel. We can savor its detail, trace the grooves in its patterned surface. We recognize the reality of the miniscule beings that sustain us, a reality that now becomes ours to sustain or to neglect.

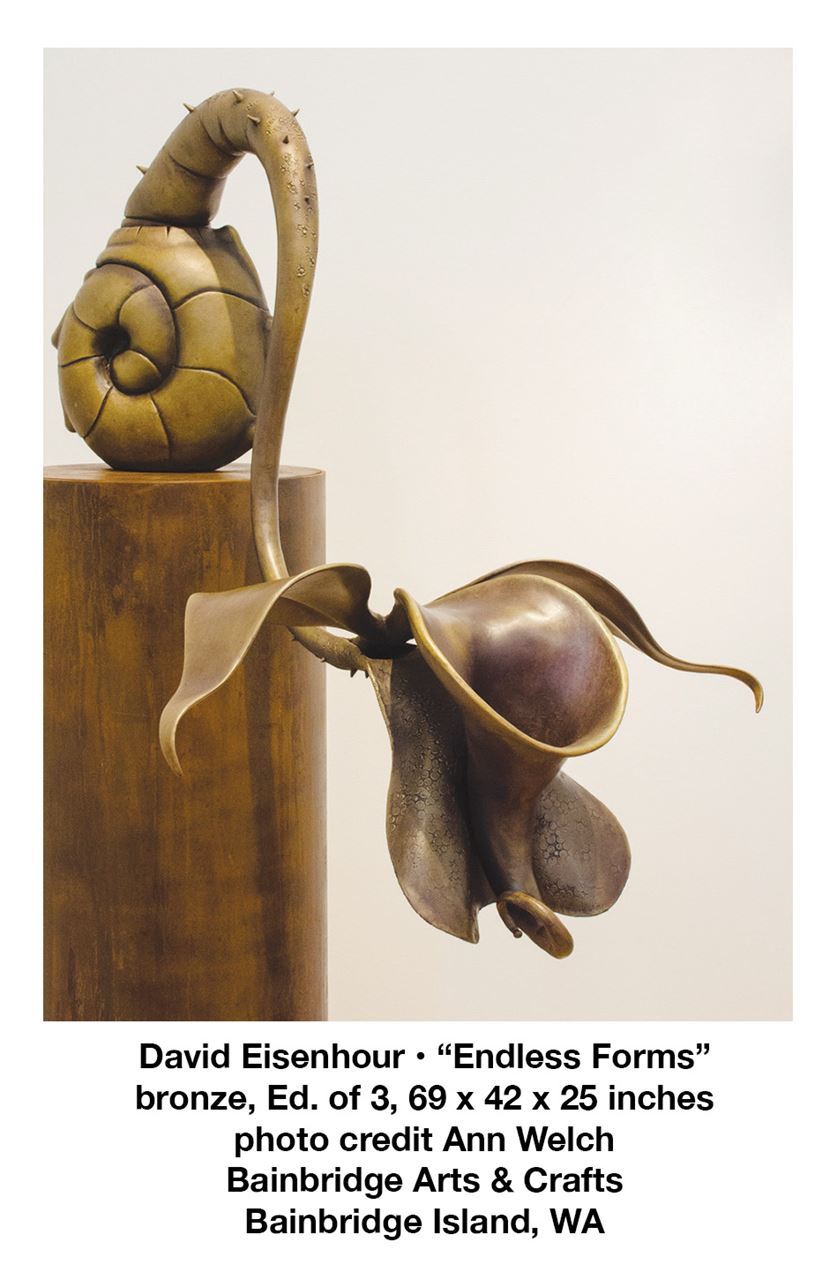

The remarkable “Endless Forms” is the show’s standout piece—literally. From its coiling chambered base it extends the long elegant curve of its limb far from its pedestal and into the gallery space, where it unfurls a jubilation of foliate forms. Form from form from form—just as its title implies.

The remarkable “Endless Forms” is the show’s standout piece—literally. From its coiling chambered base it extends the long elegant curve of its limb far from its pedestal and into the gallery space, where it unfurls a jubilation of foliate forms. Form from form from form—just as its title implies.

Tom McDonald

Tom McDonald is a writer and musician living on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

Christian Carlson and David Eisenhour exhibits are on view daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. through March 31 at Bainbridge Arts & Crafts, located 151 Winslow Way East on Bainbridge Island, Washington. For information, visit www.bacart.org.