Saya Moriyasu: Ozekitachi - Stone Tails

J. Rinehart Gallery in Seattle, Washington

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s momentous book on botany and the indigenous relationship to the natural world, the author describes her difficulty learning a Native American language; there were no nouns for bodies of water: no “bay”— only a verb meaning “to be a bay.” In her struggle, she reaches epiphany: for indigenous people, water is a living being, not an object; it may decide to be a bay, or a river, or an ocean, but it maintains its identity as water: as a living, spiritual presence with its own consciousness—and as humanity’s relative.

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s momentous book on botany and the indigenous relationship to the natural world, the author describes her difficulty learning a Native American language; there were no nouns for bodies of water: no “bay”— only a verb meaning “to be a bay.” In her struggle, she reaches epiphany: for indigenous people, water is a living being, not an object; it may decide to be a bay, or a river, or an ocean, but it maintains its identity as water: as a living, spiritual presence with its own consciousness—and as humanity’s relative.

There is a similar spirit at work in “Ozekitachi - Stone Tails,” Saya Moriyasu’s solo show of sumi paintings, ceramic sculptures, and small, hand-built clay figures at J. Rinehart Gallery. A Portland-raised artist with a Japanese father, Moriyasu is leaning into her heritage, into the indigenous Japanese Shinto religion, in which the spirits of nature are recognized and revered as they are in the spiritual traditions of the First People of the New World.

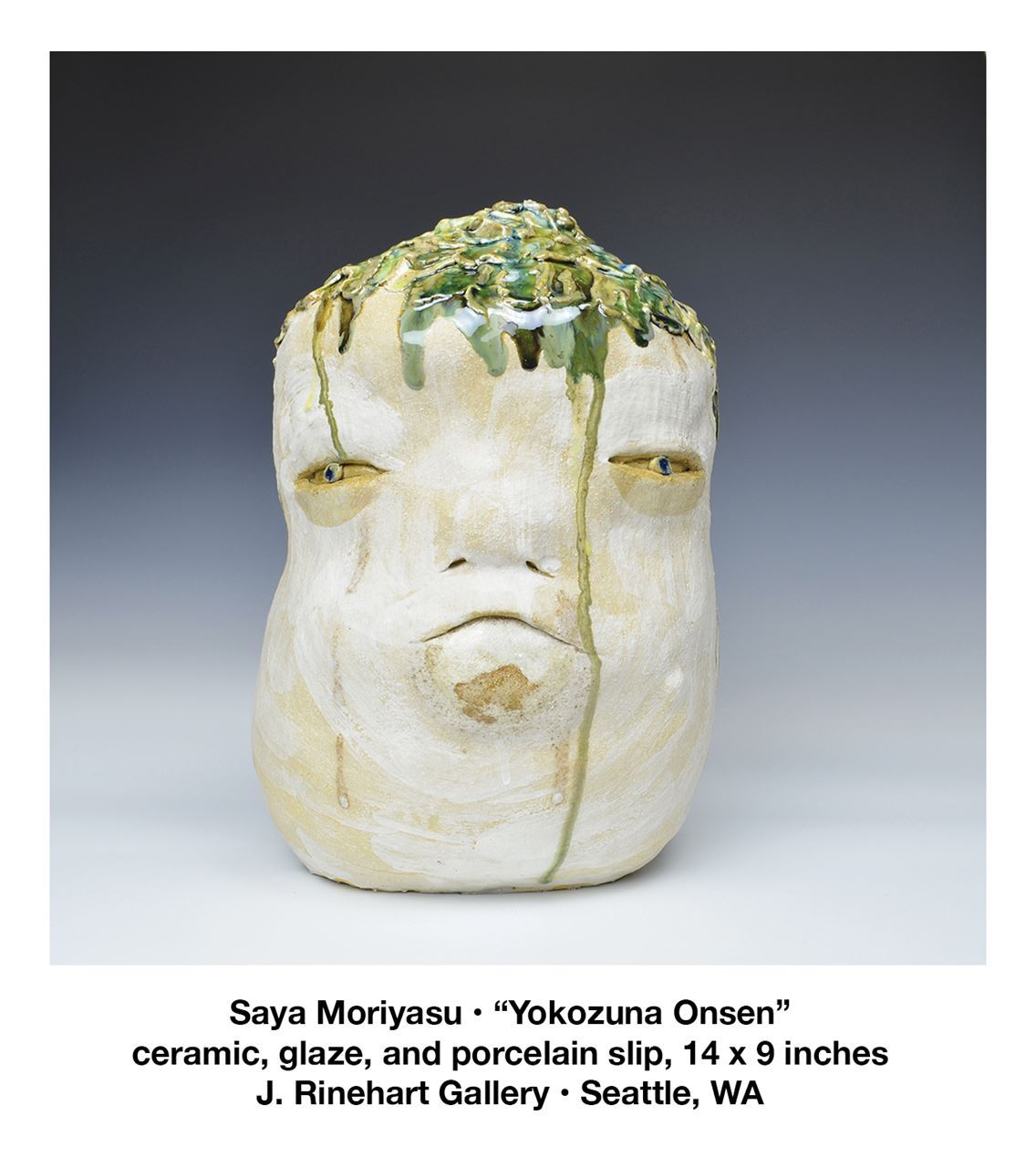

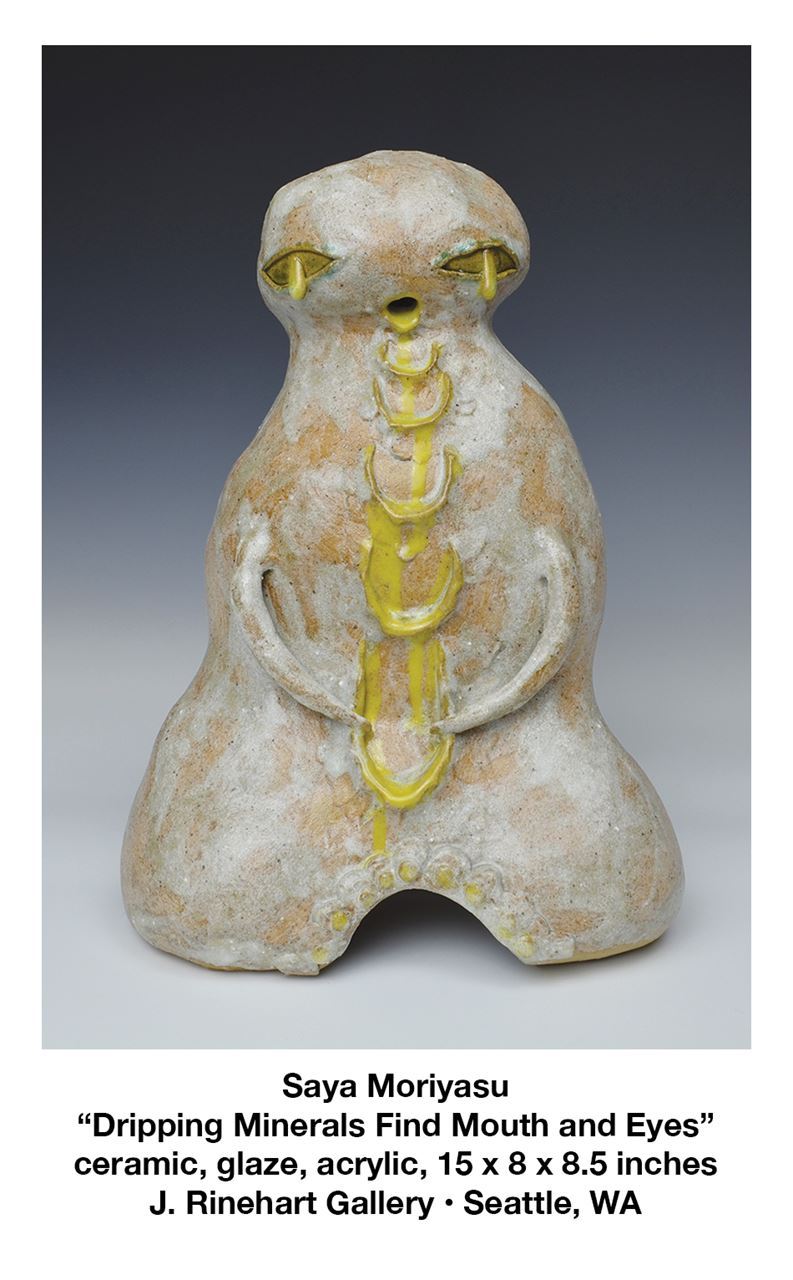

For this latest work, Moriyasu was inspired by mineral springs encountered on the road trip to a New Mexico residency. She describes soaking in hot springs, feeling “enveloped in the wordless communication of the waters,” in the “presence of deities of the depth.” She sought to express, in ink and clay, those spirits and named her creations Onsen (“hot spring”) creatures. In Moriyasu’s conception, as they encounter human presence, the Onsen creatures awaken, rising to the surface and communicating through minerals exuded through their eyes and mouths.

Moriyasu is concerned about our relationship to the earth; she uses a green process of creating art: rainwater and solar-powered kilns, hybrid car, and eating low on the food chain. Using earth-sourced clay, she lets her hands find where faces hide. Hand-sized, her creatures invite touch. She leaves them lumpen, Caliban-like, some little more than piles of sediment with pareidolic suggestions of a face. “Blue Kappa Is Watching” is a seaweed-covered lump of mud with two large staring eye-spots; a Sumo-loving, reptilian water spirit, the kappa becomes lethal when not respected.

Moriyasu is concerned about our relationship to the earth; she uses a green process of creating art: rainwater and solar-powered kilns, hybrid car, and eating low on the food chain. Using earth-sourced clay, she lets her hands find where faces hide. Hand-sized, her creatures invite touch. She leaves them lumpen, Caliban-like, some little more than piles of sediment with pareidolic suggestions of a face. “Blue Kappa Is Watching” is a seaweed-covered lump of mud with two large staring eye-spots; a Sumo-loving, reptilian water spirit, the kappa becomes lethal when not respected.

Some of Moriyasu’s creatures take their names from geologic formations. Her “Meromixis” Onsen creatures are named for a type of deep lake whose temperature differential at different depths prevents complete mixing, causing stratification of the water. Glazed black on the bottom like the primal slime they emerge from, the white porcelain-slip tops gape comically like a kindergartener’s clay ghosts, green puddling in their eyes, spilling as drool from their mouths.

Larger than most, “Geode Rises from Stomatolite” references a mysterious, tube-shaped, layered, sediment formation that has provided fossils of the most ancient life on earth. Moriyasu’s creature hides a double identity: a green, frog-like face peers from the interior of the mouth—a hidden geode. Red kumihimo (Japanese braids used for samarai swords) streams from his eyes like tears.

Larger than most, “Geode Rises from Stomatolite” references a mysterious, tube-shaped, layered, sediment formation that has provided fossils of the most ancient life on earth. Moriyasu’s creature hides a double identity: a green, frog-like face peers from the interior of the mouth—a hidden geode. Red kumihimo (Japanese braids used for samarai swords) streams from his eyes like tears.

Moriyasu has designated her Onsen creatures Ozekitachi, members of the Ozeki, the second-highest rank in Sumo wrestling. Sumo has roots in the Shinto religion, originating as supplication and entertainment for the kami, the spirit deities of nature. Sumo also has its place in the Shinto creation story; through violent Sumo battles, the kami gained superiority over common humans and, through their battles, the earth with sun and moon was formed.

Many of her creatures do have the rotundity and sweetness of modern Sumo wrestlers. Like Sumo, they seem playful, yet hint of power and strength. (“Yokozuna Onsen,” his title designating him as a grand master of Sumo, rises above the slime, amphibious features exuding dignity and evaluation.) And as we who live under the looming threat of the overdue “Big One” know, ancient geology is not to be taken lightly. Like the kami, nature has two faces: it can nurture, and it can destroy.

Moriyasu tells us that “Ozeki” can be translated as “Tail of the Stone”—and hence the title of the show and also perhaps a pun: these are the tales that stones might tell, if stones could tell tales. And here they can and do, speaking of the ancient origins of life and an alternative relationship with the earth, reminders of our deep connection with the earth—and the earth’s powerful need for our respect and care.

Elizabeth Bryant

Elizabeth Bryant

Elizabeth Bryant tutors English and writes about art.

“Ozekitachi - Stone Tails” is on view through March 27 at J. Rinehart Gallery, located at 319 Third Avenue South in Seattle, Washington. The Opening Reception is on Thursday, March 7, 5-8 p.m. An Artist’s Talk is on Saturday, March 16, from 2 to 4 p.m. For more information, visit www.jrinehartgallery.com.