LOVERULES

Henry Art Gallery • Seattle, Washington

Hank Willis Thomas plays tricks on us in order to see racism before our very eyes. The artist began his tour of “LOVERULES” with “An All Colored Cast,” a painting that looks like bright squares of minimalist color. But when we took a flash photo of it, we suddenly saw that each square had a portrait of a famous Black actor, singer, or performer. Thomas is pointing out that no matter how famous Black performers are they are still much less visible than white performers. To underscore this, there was no list identifying the performers.

Another theme is sports. Near the door of the Henry Art Gallery a ten-foot tall shiny steel arm spinning a basketball looms over us. The title is “Liberty (reflection).” We can immediately see the irony in the celebration of this glorious arm. It echoes the Statue of Liberty and its torch; so does basketball lead to equality and freedom as promised by the statue? Hank Willis Thomas wakes us up to the truth starring us in the face, that there is no equality and freedom through sports or other means promoted to Black people to escape racism.

Another theme is sports. Near the door of the Henry Art Gallery a ten-foot tall shiny steel arm spinning a basketball looms over us. The title is “Liberty (reflection).” We can immediately see the irony in the celebration of this glorious arm. It echoes the Statue of Liberty and its torch; so does basketball lead to equality and freedom as promised by the statue? Hank Willis Thomas wakes us up to the truth starring us in the face, that there is no equality and freedom through sports or other means promoted to Black people to escape racism.

A partner piece to this large arm is “Endless Column,” in the main gallery: a stack of dark blue fiberglass basketballs with a shiny finish directly imitates Brancusi’s original “Endless Column,” a monument to soldiers who died in World War I defending their town against German forces. In this case, by using the same title, Thomas suggests an homage to individuals and sports players, but with a dark edge that echoes that Brancusi homage.

An homage to people killed by gun violence, “20,923 (2021)” puts a white star embroidered on a blue flag, drapedon the ground—one star for every personmurdered by guns in the U.S. in 2021. The numbers are staggering, indicated by the title, exceeding deaths in foreign wars.

As a result of the death of his cousin and close friend in a vigilante attack in 2000, apparently to take a gold necklace, Thomas has pursued the theme of the grotesque stereotypes and racist lies contained in commercial advertising images. He found it obscene that the murder occurred basically to obtain a commodity. The role of advertising in creating status had become a deadly promise.

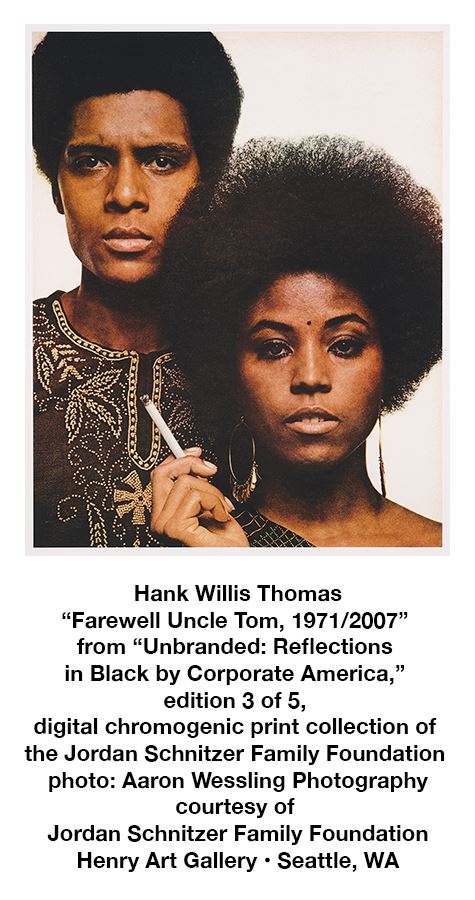

Included are two series of photographs called “UnBranded,” one with the subtitle “Reflections in Black by Corporate America,” the other subtitled “A Century of White Women.” Thomas removes the text from the advertising images and gives his own titles to the work.In the case of “Reflections in Black by Corporate America,” one example is “Farewell Uncle Tom, 1971/2007.” It shows a Black couple wearing clothing and hairstyles popular at the time,one smoking a cigarette; the image suggests the contradiction of the effort to be in touch with the 1970s and its glamorization of cigarette smoking.

Included are two series of photographs called “UnBranded,” one with the subtitle “Reflections in Black by Corporate America,” the other subtitled “A Century of White Women.” Thomas removes the text from the advertising images and gives his own titles to the work.In the case of “Reflections in Black by Corporate America,” one example is “Farewell Uncle Tom, 1971/2007.” It shows a Black couple wearing clothing and hairstyles popular at the time,one smoking a cigarette; the image suggests the contradiction of the effort to be in touch with the 1970s and its glamorization of cigarette smoking.

In “A Century of White Women” (which fills a large gallery) we see women in suggestive poses dating from 1915 to 2015. All of them are rife with sexual puns or explicit racial hierarchies. The artist declares that women are being consumed by this advertising, made into objects and exploited. The advertisements targeting Black audiences rely on the super-beautiful and the cliché.

A third category of work plays with our racism using words: “Pitch Blackness Off Whiteness” is a neon sign that flashes alternately on these four words plus “ness” to create combinations as it flashes, such as “Pitch Black” and “Off White”—color speaking to the subtleties of color beyond a binary.

Words and images stray into violence in the “Absolut” series, such as the silhouette of the bottle as the “Door of No Return” through which enslaved people were forcibly sent to America, or such as “Absolut Reality,” in which a murdered Black man lies on the sidewalk, his blood in the shape of the bottle.

.jpg) Hank Willis Thomas strips the pretense from American society. His work reveals the racism and sexism ingrained in our culture through advertising and language. He creates art that leads us to activism, both in our own lives, by rethinking clichés of racism and its violence, and in public, though resistance to the suffocating pressure of cultural norms. The images he finds are so potent that we can’t help but be inspired to fight for change. It is remarkable that this confrontational exhibition comes from one individual private collector.

Hank Willis Thomas strips the pretense from American society. His work reveals the racism and sexism ingrained in our culture through advertising and language. He creates art that leads us to activism, both in our own lives, by rethinking clichés of racism and its violence, and in public, though resistance to the suffocating pressure of cultural norms. The images he finds are so potent that we can’t help but be inspired to fight for change. It is remarkable that this confrontational exhibition comes from one individual private collector.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes for local, national, and international publications and her website, www.artandpoliticsnow.com.

“LOVERULES” is on view through August 4, at the Henry Art Gallery, located at 15th Avenue NE & NE 41st Street. Hours are Thursday from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. and Friday to Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5p.m. For further information, visit www.henryart.org.