Bronze. Aluminum. Silver, gold, and copper. Iron. Cast iron. Steel. Forged steel, mild steel, stainless steel.

Bronze. Aluminum. Silver, gold, and copper. Iron. Cast iron. Steel. Forged steel, mild steel, stainless steel.

When I first saw the theme of this year’s BAM Biennial at the Bellevue Arts Museum—“metal”—it didn’t occur to me how many variations of the material actually exist in this earthly realm. It is one of the most base materials available to artists today. Forged from the ground itself, mined and dug up and extracted from the earth, metal possesses an inherently primordial quality in its very makeup. The flip side, though, is that metal, perhaps more than any other material, conjures a sense of the metaphysical, the cosmic, the supernatural. Metal means alchemy, that ancient sorcery of transforming lead into gold. Metal means magic.

The 49 Northwest artists included in this year’s BAM Biennial “Metalmorphosis” explore this and many more of the paradoxes intrinsic to metal. It is both liquid and solid, soft and hard, stable and malleable. Metal has a long history in this region, as local Northwest tribes have made good use of the abundance of copper here for centuries. The maritime industry in the Northwest has also helped generate a large population of metalworkers and tradesmen here. Our region has a history of exploiting the technical possibilities of metal, ultimately resulting in the establishment of the aerospace industry here in the early 20th century.

Functionally, metal has a history of driving technological innovation and progress. Artistically, however, historians have long been fascinated with the question of how metal in particular has driven artistic breakthroughs.

For many artists in the show, one gets the sense that metal and its infinite possibilities and associations are driving the form. Chris McMullen’s “Haystack” is a prime example of this—the giant wall-mounted steel rods and bronze bearings come alive when you turn the crank at the bottom. Undulating and swelling in time as you crank, the piece recalls a writhing insect in its movements, a sharp departure from the mechanized heaviness of the piece in stillness.

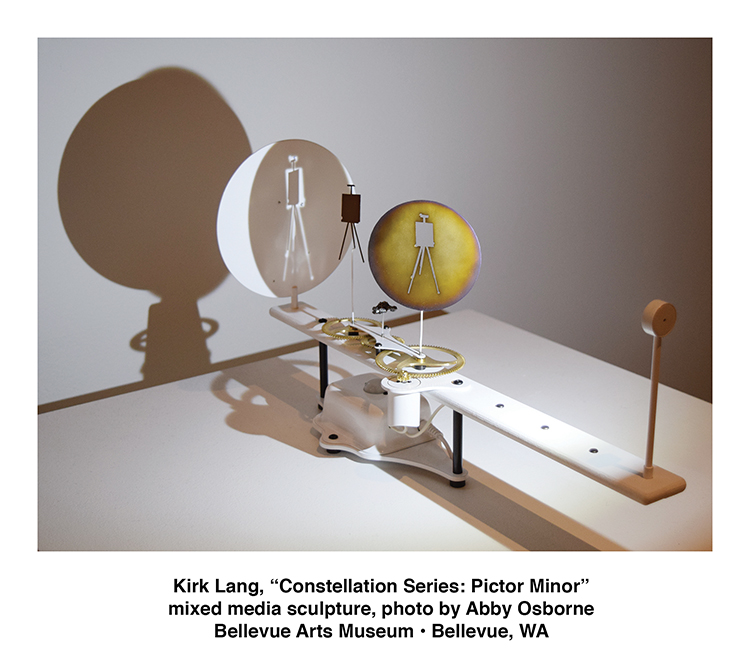

For other Biennial artists, however, metal is merely means of solving a problem or visualizing an idea. Kirk Lang’s “Constellation Series” uses a light beamed onto thin metal cutouts to cast shadows on the walls behind. The metal forms rotate and move, breaking the shadow image apart and bringing it back together as gears silently crank. The mechanisms producing this movement are clearly visible, but the magic of the image produced by the shadows somehow remains otherworldly.

Some of the most successful pieces in “Metalmorphosis” are the ones that explore the expansive, volumetric qualities of metal. That capture its ability to be both formless and any form at all, flowing through space like soft waves as in Ruth Beer’s work, or bolstering the fortress doors of a cabinet, as in Maria Cristalli’s “Perfect External Disorder.”

Some of the most successful pieces in “Metalmorphosis” are the ones that explore the expansive, volumetric qualities of metal. That capture its ability to be both formless and any form at all, flowing through space like soft waves as in Ruth Beer’s work, or bolstering the fortress doors of a cabinet, as in Maria Cristalli’s “Perfect External Disorder.”

Maria Phillips’ piece “Mapping Monotony” immediately captures your attention upon entering the exhibit, certainly in part because of its scale. But then, its texture. Incomprehensibly whispy pieces of steel dot the white wall, cascading down in tufts and patches of metal that beg to brushed and combed. When I heard another gallery-goer describe the image as “snow-covered grasses,” I did a double take. The white wall now stood in as snow, with the metal tufts reading as plant-like protrusions. That is the beauty of metal—it can take any form we dream it to be.

Catherine Grisez similarly explores the malleability of metal in her collection of pieces, titled “Dignifier,” “The Compromise,” and “Surrender,” which all attempt to treat copper as a kind of skin. Melting off corners and sliding down edges, the works alternately resemble gooey caramel and that weird spray-foam insulation. Grisez is able to instigate the odd feeling that comes when you can’t tell what something is made of by its form. Her forms hint they should be something they’re not. These pieces, made out of copper, should say, “Hard.” But the forms—squishy, layered, melted-ice-cream-like shapes—say, “Soft.”

Many artists in “Metalmorphosis” take a different tact, drawing not on the forms of metal, but on its association with machinery and mechanization—the technology that has helped us go faster and stronger as a society. However, rather than blindly embracing this forward movement, several of the Biennial artists question whether this is necessarily “progress.” David Keyes, in his work “Classicism Fleeing the Onslaught of Modernism,” features cast-bronze classical figures being flattened by the printing press. Literally—the piece incorporates a cast iron roller from an actual 19th-century printing press. Keyes makes us wonder how much our reliance on technology and mechanization has similarly flattened our culture, reduced as we are to looking at screens.

Andrew Fallat’s kinetic sculpture, “Novelties in Simulacra,” is beautiful in its reminder of how clumsy this technology can actually be. Metal gears, levers, and weights clank together awkwardly, in no sort of rhythm and with no clear purpose. Coming to life at random times, I was in the other room when all of a sudden I heard it begin to move and ran to see what all the ruckus was. There is something ancient and imperfect about Fallat’s work, despite the gears and pulleys pleading of their modernity.

Perhaps this is the ultimate beauty of metal. As much as we pull and ply it into modern forms and shapes, it will always be ancient and base. The artists in “Metalmorphosis” remind us that this material, in its infinite uses and formal possibilities, will always speak of its original home. It will always bring us back down to earth.

Lauren Gallow

Lauren Gallow is an arts writer, historian, and editor. You can read more of her work and learn about her immersive art project “Desert Jewels” at www.desert-jewels.com/writing.

“Metalmorphosis” is on view through February 5, 2017 at the Bellevue Arts Museum, located at 510 Bellevue Way NE in Bellevue, Washington. Hours are Tuesday through Sunday from 11 A.M. to 6 P.M. For more information, visit www.bellevuearts.org.