Ukranian-born American sculptor Alexander Archipenko set out to do the impossible. He sought to represent movement in sculpture. In “Archipenko: A Modern Legacy,” on now at the Frye Art Museum, the artist’s lifelong quest to expand the definitions and possibilities of sculpture raises a larger question about what it means to be an artist. About what an artist’s role in society can be.

Ukranian-born American sculptor Alexander Archipenko set out to do the impossible. He sought to represent movement in sculpture. In “Archipenko: A Modern Legacy,” on now at the Frye Art Museum, the artist’s lifelong quest to expand the definitions and possibilities of sculpture raises a larger question about what it means to be an artist. About what an artist’s role in society can be.

For Archipenko, the role of the artist was one of provocateur. Of driving forward and instigating social change through artistic production. Aligning himself with avant-garde artistic and literary groups quite early on in his career and all through it, Archipenko consistently experimented with what the sculptural form could (and couldn’t) do.

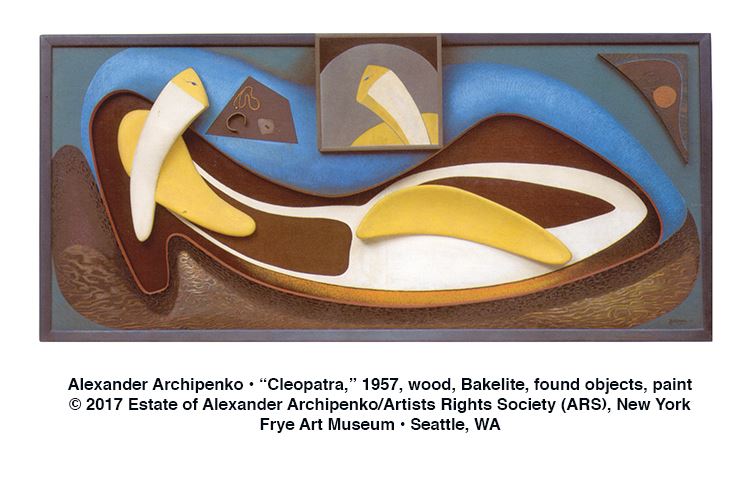

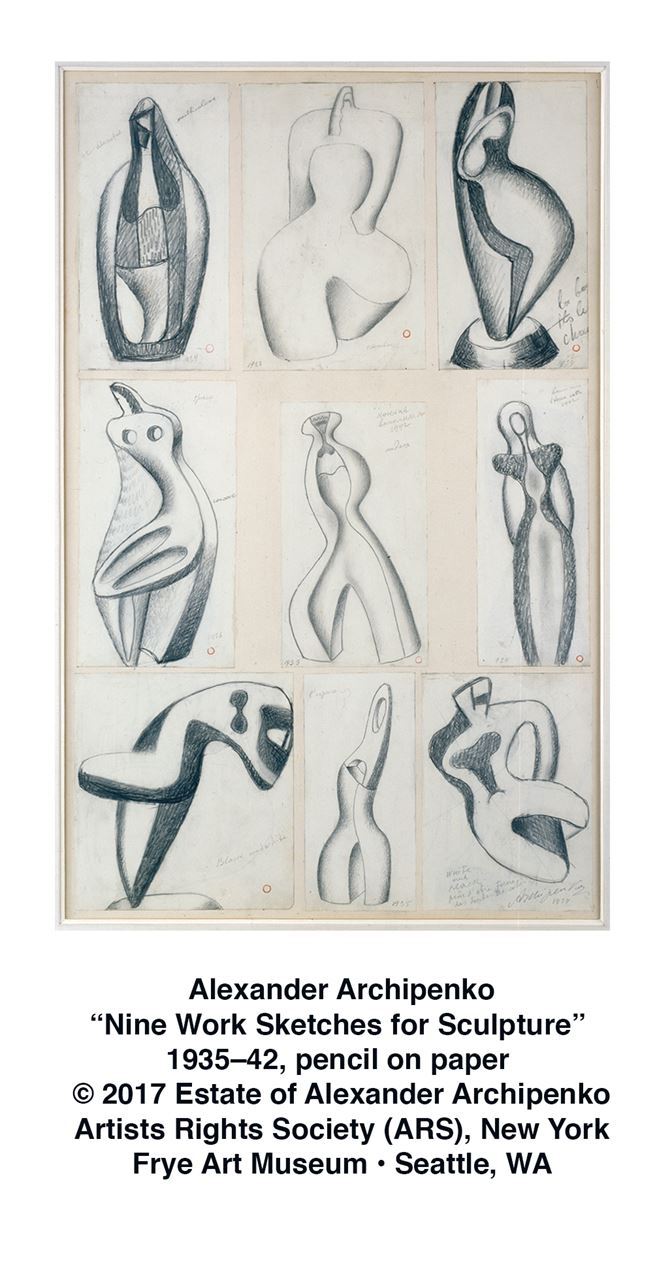

Walking through the exhibit at the Frye, which is organized chronologically—(the historian in me rejoices!)—visitors can trace the evolution of these experimentations in his abstract figurative sculptures. The moments where Archipenko really nails it, where the single curve of a hip or outline of a shoulder can suggest the most graceful saunter or the most delicate repose, are made all the more successful when seen next to the drawings and sketches where he was working out these ideas.

At the beginning, Archipenko’s more modern, abstract sculptures are juxtaposed against an equal number of works adhering to more classical representations of the human form. A lifelike, white marble sculpture from 1921 effortlessly reads as a figure: the face is abstracted and one arm is truncated, but the all-too-familiar form of the reclining female nude is easy to discern. In case you still had doubts, just read the title: “Reclining.” Case closed.

Right next to “Reclining,” however, is “Walking” from 1912-18, a bronze sculpture that gestures at the human form, but abstracts and breaks it apart as much as constructing it. Here, Archipenko pushes the boundaries of what signifiers are needed in order for a sculpture to read as “human figure.” A vertical rectangular form at the bottom suggests “leg,” while the hourglass shape above reads “torso,” and the circular form on top suggests “head.” Much like the Cubists with whom he was often associated, Archipenko questions the very forms of representation themselves. “How much can I abstract the shape of the body,” he seems to be asking, “until it no longer reads as human at all?”

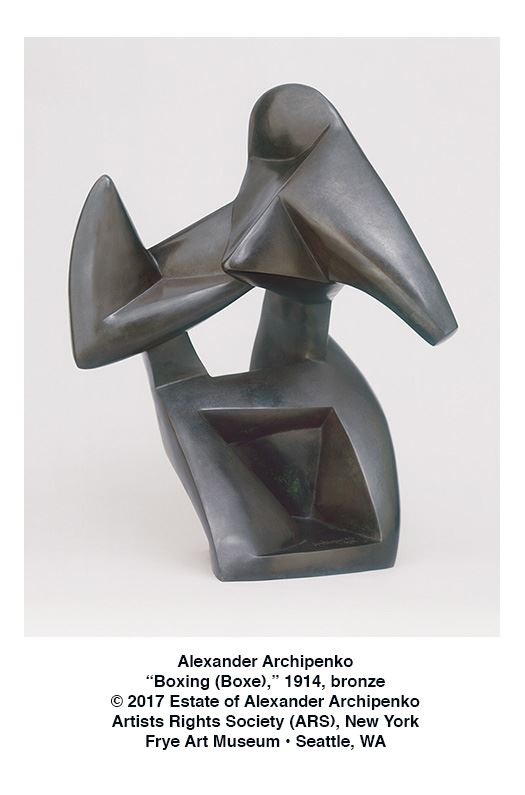

While many of Archipenko’s sculptures walk the line between representation and abstraction, many fall over into pure abstraction, where the human form is hardly recognizable at all. In “Boxing,” the sculpture is so abstract that the title might be the only way to discern what he is representing.

Forms and masses meld together and are barely readable as two figures dueling. In the middle of the sculpture is a hole—Archipenko’s trademark move. Putting negative space in the middle of a sculpture, the medium that is supposed to be about form and mass. This is what Archipenko is known for: sculpting the void. Representing nothingness. In so doing, Archipenko seems to be asking, “What are we trying to do here, anyway?”

Because the larger question informing Archipenko’s work is not so much about representation vs. abstraction, positive vs. negative space, movement vs. stasis. It’s about what the artist can do. It’s about how far an artist can push the boundaries of representation, can push the limits of what’s acceptable, and still be understood.

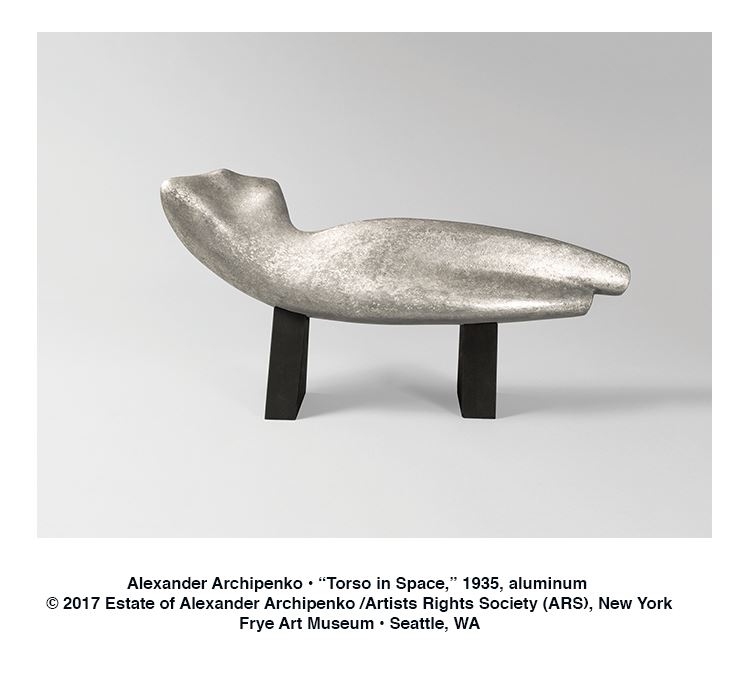

Archipenko’s most successful works are the ones where he stretches these limits to their max, reducing the form down to its most essential parts, stripping away the layers of excess. “Torso in Space” from 1935 is nothing more than two curves and a line. But it nevertheless reads as a torso in the clearest, most modern way. Here, Archipenko proves that testing the boundaries of what’s possible can yield highly elegant results.

We know that the history of Western art is a history of vanguard movements. It is a history of artists pushing the limits of what’s acceptable in art making. We remember those artists who went against the grain, who questioned their culture and tried to critique it in some way. Picasso, Monet, Rodin, Van Gogh, Warhol. We tend to forget it now, but all of these artists were considered radicals in their owntime. Add Archipenko to that list—his experiments in sculptural abstraction parallel that of Brancusi or Boccioni.

We know that the history of Western art is a history of vanguard movements. It is a history of artists pushing the limits of what’s acceptable in art making. We remember those artists who went against the grain, who questioned their culture and tried to critique it in some way. Picasso, Monet, Rodin, Van Gogh, Warhol. We tend to forget it now, but all of these artists were considered radicals in their owntime. Add Archipenko to that list—his experiments in sculptural abstraction parallel that of Brancusi or Boccioni.

What Archipenko and the rest of these artists tell us is that the status quo will always be there. There will always be rules and guidelines about what is possible or acceptable, in the world of art and in the larger culture by extension. It’s the role of the artist, the cultural provocateur, to challenge this status quo. To test its limits and possibilities, to experiment and question. Or, in the case of Archipenko, to blow a hole right through the middle of it.

Lauren Gallow

Lauren Gallow is an arts writer, critic, and editor. You can read more of her work and learn about her immersive art project “Desert Jewels” at www.desert-jewels.com/writing.

“Archipenko: A Modern Legacy” is on view through April 30 at the Frye Art Museum, located at 704 Terry Avenue in Seattle, Washington. Hours are Tuesday through Sunday from 11 A.M. to 5 P.M. Admission is always free. For more information, call (206) 622-9250 or visit www.FryeMuseum.org.