The genre of portraiture doesn’t get a lot of love these days. Come to think of it, it never really has.

In the Royal Academy—the post-Renaissance prototype for today’s art schools and museums where the best of the best European artists trained—portraiture was second on the hierarchy of genres. Any artist who wanted to paint “important” works in the academy was producing History Paintings, depicting mythological or religious subjects to

convey some kind of higher ideal or moral value. Portraiture was important —it sat above landscape painting and still lifes on that academy list—but it wasn’t number one. In general, Western portrait painters were respected for their technical skill and ability to produce a

recognizable likeness of a person, but not so much for their ideas or creativity.

And so it has been for the last several centuries. Portrait painters have rarely made a splash or even a ripple in the trajectory of art history—can you name any portraitists off the top of your head? Recently, however, portraiture has made a comeback. Barack and Michelle Obama’s presidential portraits were unveiled recently, throwing a wrench in the historically conservative and— I’ll say it—downright boring collection of the last 200 years of presidential portraits. Kehinde Wiley’s depiction of Barack in a lush garden of green leaves and pops of colorful flowers and Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle in a bold patterned dress against a bright blue background have been a breath of fresh air. How refreshing to see portraits that buck conventions, toss off the unspoken requirement of literalism, and attempt to say something about the personalities of these important people. Portraiture is back.

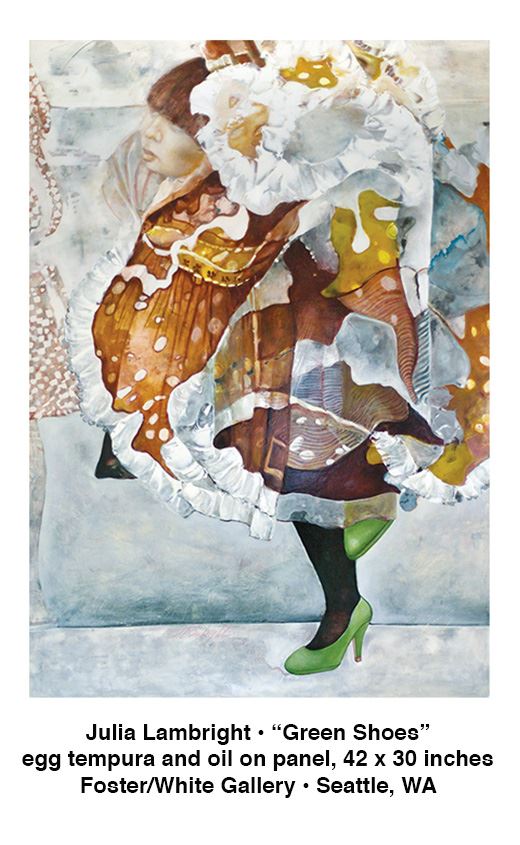

Just take the current show at Foster/White Gallery, aptly titled “Portraiture.” The show brings together three painters whose work expands and questions the nature of portraiture as a genre. Erin Armstrong, Carlos Donjuan, and Julia Lambright prod and push at the boundaries of portraiture—somewhere in the middle of my time with the paintings, I found myself asking, what makes a portrait a portrait? Just as Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald offered a courageous new answer to this question with their Obama portraits, the artists in “Portraiture” proffer up three similarly bold responses.

California-based painter Erin Armstrong tests the parameters of portraiture with

a body of work where the visual identity of her sitters is all but obscured. Bright splashes of color and bold floral patterns surround and define her subjects, sometimes encroaching on, but never overshadowing, the human forms she depicts. It’s the form, the container that stays in tact—the context and the contents transmute. Boundaries are strongly defined, but what lies within or just without that edge is amorphous.

For Armstrong, the frontier of identity is anything but settled. It’s wild and blooming, neon lights and floral wallpaper, bright and budding and just a little bit cheeky.

Armstrong’s figures embody an identity or a character, but the defining physical features are concealed or abstracted. One subject covers her face with a bouquet of bright blue tulips. Another has an orange stripe for an eyebrow and a head composed of turquoise, yellow and purple stripes. The face—the place we often look first to locate identity—is the focus, but there are no distinguishing features to be found in Armstrong’s portraits. Instead, we are left with a container, a form filled with a sensation or a color or a bouquet of bright blue tulips.

Smaller in scale but richer in symbolism are the delightfully ambiguous paintings of Carlos Donjuan. Based in Dallas, Texas, Donjuan works from his personal history as a first generation American to address notions of belonging. Fascinated from a young age with the concept of alien identity, Donjuan’s portraits toe the line between standard and strange. Here, portraiture addresses the place of the person in the land of the collective. While Armstrong locates identity within a vessel of ever-evolving sensations, Donjuan finds it in the act of assemblage. In Donjuan’s paintings, delicately rendered strands of hair are tucked behind a mask of geometric patterns and leopard print. Human faces are abstracted to triangles and circles, which then become the composite parts of the chorus of friendly creatures populating his works. Identity for Donjuan is a kit of parts that can be endlessly reconfigured and mixed and matched. We all wear masks, he seems to say. Some are friendly, some are funny and some are foreign. They all speak to the impossibility—the absurdity—of ever truly blending in.

Smaller in scale but richer in symbolism are the delightfully ambiguous paintings of Carlos Donjuan. Based in Dallas, Texas, Donjuan works from his personal history as a first generation American to address notions of belonging. Fascinated from a young age with the concept of alien identity, Donjuan’s portraits toe the line between standard and strange. Here, portraiture addresses the place of the person in the land of the collective. While Armstrong locates identity within a vessel of ever-evolving sensations, Donjuan finds it in the act of assemblage. In Donjuan’s paintings, delicately rendered strands of hair are tucked behind a mask of geometric patterns and leopard print. Human faces are abstracted to triangles and circles, which then become the composite parts of the chorus of friendly creatures populating his works. Identity for Donjuan is a kit of parts that can be endlessly reconfigured and mixed and matched. We all wear masks, he seems to say. Some are friendly, some are funny and some are foreign. They all speak to the impossibility—the absurdity—of ever truly blending in.

The third artist in the exhibit, Julia Lambright, dives even deeper into the layered facets of identity in the genre of portraiture. Born and raised in Russia, Lambright works in a traditional egg-tempera painting technique which she learned from masters in Russia and the United States. A notoriously unforgiving medium, egg-tempera is a technique ripe with historical associations. Lambright describes her work as “excavating the strata of the past,” building up layers of symbols and textures to compose the iconic figures who populate her paintings. For her, identity is about history—it can be built up and unearthed through the layers of time.

Their methods and influences are quite different, but all three artists in “Portraiture” bring similar questions to the table: where do we locate individual identity? And how does the body in concert with its context work to convey this sense of self? At a moment in history when identity—whether gender, racial or national—holds more political relevance than ever, it seems fitting that artists are using the genre of portraiture to play with these definitions. Because, the truth is, portraitists have always used their medium to communicate carefully orchestrated messages about

their sitters. They just haven’t always been quite so honest about it.

Lauren Gallow

Lauren Gallow is an arts writer, critic, and editor. You can read more of her work at www.desert-jewels.com/writing.

“Portraits” is on view through March 24 at Foster/White Gallery, located at 220 Third Avenue South. The gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday 10 A.M. to 6 P.M. For further information call (206) 622-2833 or visit www.fosterwhite.com.