Keep an eye out for satire in the Seattle Art Museum’s new exhibition “Figuring History.” Robert Colescott, Kerry James Marshall, and Mickelene Thomas all share a deep irreverence for traditional Euro American history as they rewrite familiar stories and turn clichés upside down and inside out. But first, immerse yourself in the sheer virtuosity of these artists. “Figuring History” the theme presented by Catherina Manchanda, curator of the exhibition and modern art curator at the Seattle Art Museum, emerges from brilliant formal games with color and space.

Fortunately, because the paintings are large (in the tradition of history painting,) there are not many of them, which makes it possible to fully experience their aesthetics, their satire, and their rewriting of history. The show encompasses three generations of African American artists. Robert Colescott (1925–2009) turned to monumental figures inspired by both Leger and Egyptian art (he lived in Cairo for several years). He was directly affected by the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s; Kerry James Marshall, born in 1955, celebrates middle class black life starting in the 1990s with its undercurrent of impending danger. Mickelene Thomas, born in 1971, brings us to the present moment with her assertive, no holds barred paintings of black women.

Colescott’s first rewriting of history, “George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware,” 1975, outraged many people with its repertoire of cliché black face figures filling the boat of the iconic representation by Emanuel Leutze’s “Washington Crossing the Delaware.” Intriguingly, this painting is more straightforward than much that followed. Colescott layers satire, caricature, and political and historical defiance. You can’t always decipher all of his references, as his mature style of loose, brushy, overlapping figures purposefully obscures the identity of many of his figures. Looking at “Afterthoughts on Discovery,” for example, Columbus is obvious in the foreground, a conquistador behind him, a slave, a native American, two skeletons, perhaps Lincoln, a Spanish priest, but what about the five people on the upper left. Are they identifiable, symbols? Or are they actual people? The same can be said for “Knowledge of the Past is the Key to the Future: Matthew Henson and the Quest for The North Pole,” 1986. African American explorer Matthew Henson who accompanied Peary to the North Pole in 1909, is rescued from oblivion as the central figure here. Around him are Peary, a slave, a white slave trader, a Native American, and a collection of other people including Salome presenting the head of John the Baptist, a half black half white woman, and a prostitute with bright green shoes and bag. So we wander through the painting, wondering how they fit together, do they fit together, does it matter? Colescott provides a virtual catalog of skin colors and types, high and low, famous and anonymous. He mixes up all the boundaries. Perhaps that is more important than a coherent single point in time.

Two tightly selected series present Kerry James Marshall here along with a few other well known paintings. Manchanda did well to fill a room with his spectacular “souvenir” series. They glitter in tones of gray, while honoring the terrible loses of the Civil Rights Era. Marshall’s work draws on every source from kitsch to classical, he plays with us, drawing us into the spaces he creates. In contrast, “The School of Beauty, School of Culture,” 2012, represents a crucial aspect of Marshall’s work, his exploration of black middle class life. Nothing is more iconic that the black beauty salon and this work offers realism, pop art references, and a hologram representation of a white blond in the foreground (a look back to what black women used to desire?), now eclipsed by absolutely self-confident black women with stunning hairdos. (For another view of this subject, see the Al Smith show “Seattle on the Spot” at the Museum of History and Industry until June 17, featuring a black beauty school in the Central District as well as other themes that reinforce the idea of ”Figuring History.)

Don’t fail to spend some time with Marshall’s “Vignette” series as well: he layers seemingly simple statements of love with pointed political references.

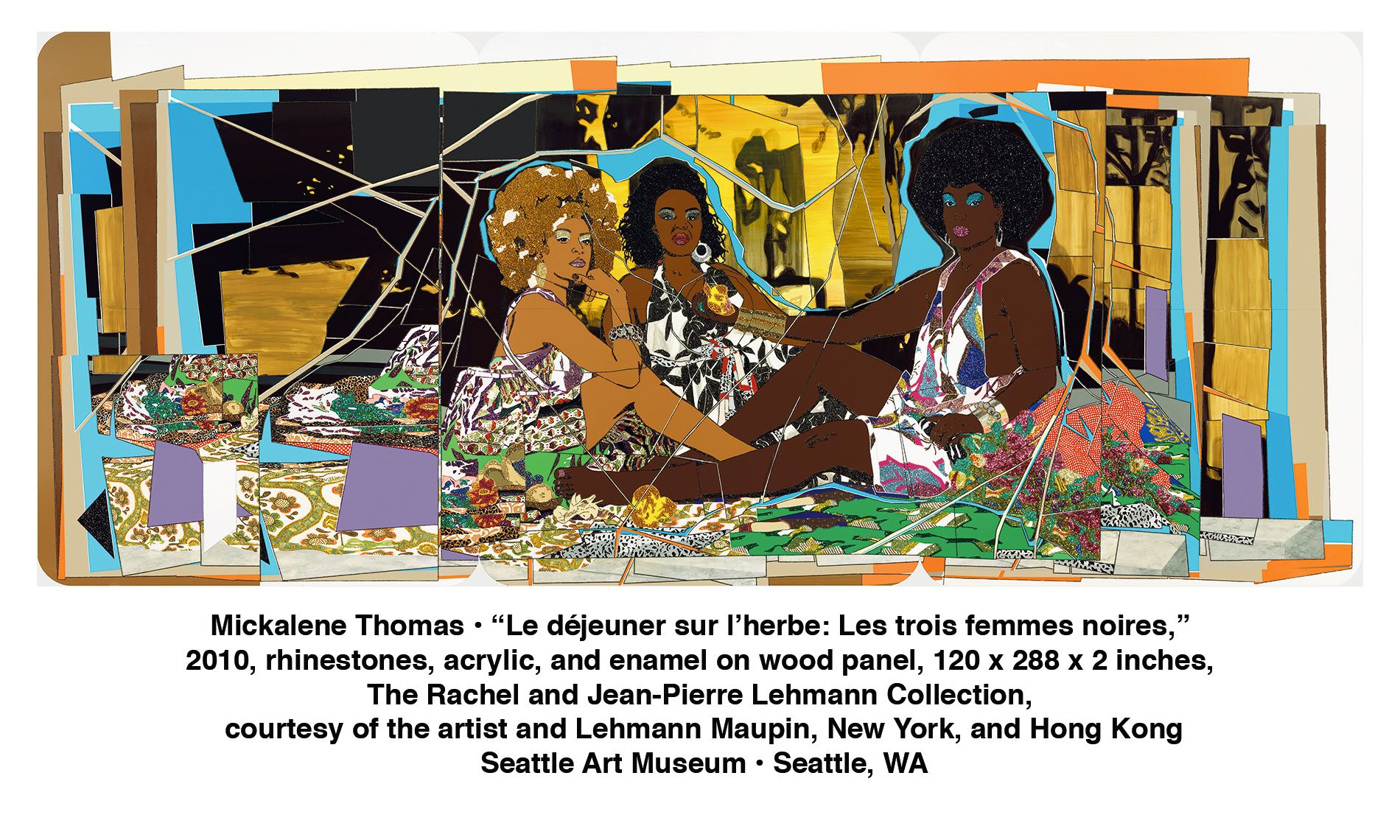

Mickelene Thomas’s glittering canvases of confident black women envelop us. Thomas, like Colescott and Marshall, sometimes redefines famous paintings. Here she transforms Manet’s “Dejeuner sur L’Herbe” into the fabulous “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires,” 2010. Thomas’s games of space are outrageous and fascinating, they pull us in and push us out; they interrupt predictable perspectives; they adeptly juxtapose modernist squares of colors with complex patterns. While Marshall depicts a shimmering curtain in reflective glitter that closes off the space behind in “Memento V,” Thomas’s shining rhinestones copiously distributed on her paintings actually push us back. That push back in Dejeuner sur l’herbe reinforces the bold, but unavailable, women at its center .

Take time with these stunning paintings, explore their complexities, and pay attention to their new histories of life in the US. It refreshes the spirit amidst the current degradations of our public politics.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com. She writes for local, national and international publications. Most recently she has curated several exhibitions on the subject of Migration.

“Figuring History” is on view through May 13, 2018 at the Seattle Art Museum, located at 1300 First Avenue in Seattle, Washington. Hours are Wednesday, Friday through Sunday 10 A.M. to 5 P.M.; Thursday 10 A.M. to 9 P.M.; and closed Monday & Tuesday. For more information, call (206) 654-3100 or visit www.seattleartmuseum.org.