Perry and Carlson Gallery & Shop • Mount Vernon, Washington

After decades working in New York and Seattle as design professionals, couple Trina Perry Carlson and Christian Carlson were primed to build a life with their personal creative imperatives on the front burner—textile-based artwork for her, abstract painting for him.

“My motivation for coming was to have time and space and creative freedom,” explains Christian, an architect. “And Trina’s was to start a retail business.”

They decided that moving to a smaller, more affordable community would set the stage for realizing their aspirations. So as their youngest child neared the completion of high school, they began looking at real estate with that ineffable “it” factor in Oregon and Washington.

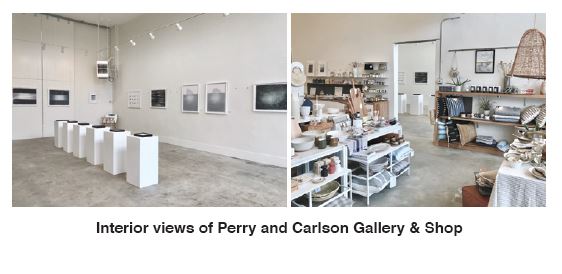

Their sweet spot turned out to be an hour north of their Capitol Hill home, in Mount Vernon, where they purchased a 6000-square-foot building in the town’s commercial heart. Since moving into the 1924 property almost five years ago, they have transformed its street-facing area into two fluidly conjoined spaces: a gallery featuring contemporary artists and a retail shop rich with handcrafted objects and vintage finds. And in the back, an enviable loft-like residence, with room for their own studio spaces.

“Mount Vernon is one of the most intact towns in the West, at least on First Street,” according to Christian. “We’re both urbanists and understand what makes a town healthy or unhealthy and Mount Vernon seemed to be doing everything right.” The pair was impressed by the town’s active farmers’ market and downtown business association, mix of retail, restaurants, cafes, and bars, and a recently completed flood wall and riverwalk.

“One thing that really spoke to us was how vibrant the community co-op is,” says Trina. “People travel from Bellingham to shop at the Skagit Valley Co-op and also to go to the Lincoln Theater. It felt like if this town supports these two really strong community-based businesses that’s a good sign.”

“One thing that really spoke to us was how vibrant the community co-op is,” says Trina. “People travel from Bellingham to shop at the Skagit Valley Co-op and also to go to the Lincoln Theater. It felt like if this town supports these two really strong community-based businesses that’s a good sign.”

They wanted to avoid the gallery being a gift shop with art on the walls. And, unlike many of the Valley galleries which mainly focus on local artists, its exhibitions have featured national and international artists.

“We were trying to make a splash with bringing more of a big city kind of art scene to the Valley,” Christian explains. “We got some nice attention for that. And then the local artists started kind of paying attention to us. And in the meantime, in the last three years, we’ve met dozens of local artists.”

Looking ahead, he says, “there are two things that we haven’t done that we would like to do. One is more focused on installations, where we invite artists to take the gallery for a month and build something in situ. And the other is new media.”

The unexpected pleasures of the move have been many. Trina explains, “We feel like we’ve built more community in the last four years than in 20 years in Seattle.” Another boon of moving to a smaller town is that “there’s a real value in getting involved. There’s room for involvement and you can make a difference. Christian’s on the planning commission now, he’s a planning commissioner and helping the city.” Collaboration with other artists, artisans and galleries has been rewarding as well.

The unexpected pleasures of the move have been many. Trina explains, “We feel like we’ve built more community in the last four years than in 20 years in Seattle.” Another boon of moving to a smaller town is that “there’s a real value in getting involved. There’s room for involvement and you can make a difference. Christian’s on the planning commission now, he’s a planning commissioner and helping the city.” Collaboration with other artists, artisans and galleries has been rewarding as well.

And Christian’s work has changed profoundly. Prior to the move, he considered himself an inveterate abstract painter. “I’d never been interested in landscape art in any way, shape, or form. To me landscape was the same as still lifes or something. It was just kind of too representational and too sort of light.”

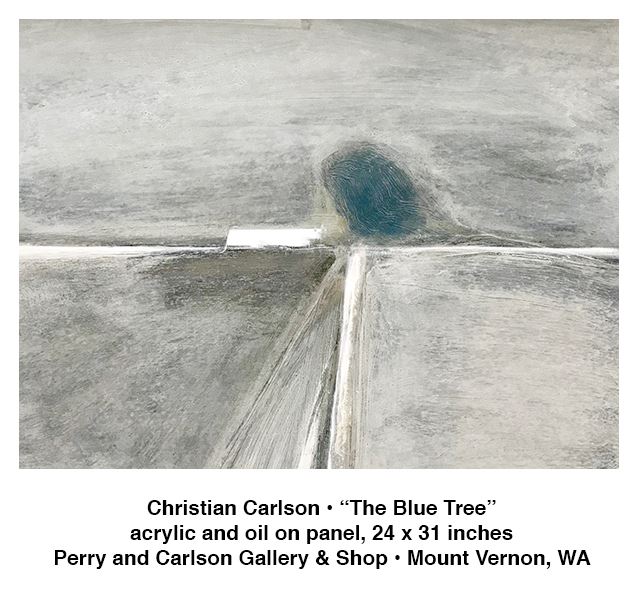

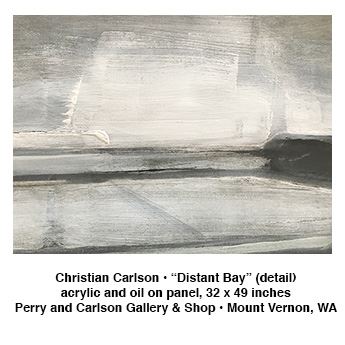

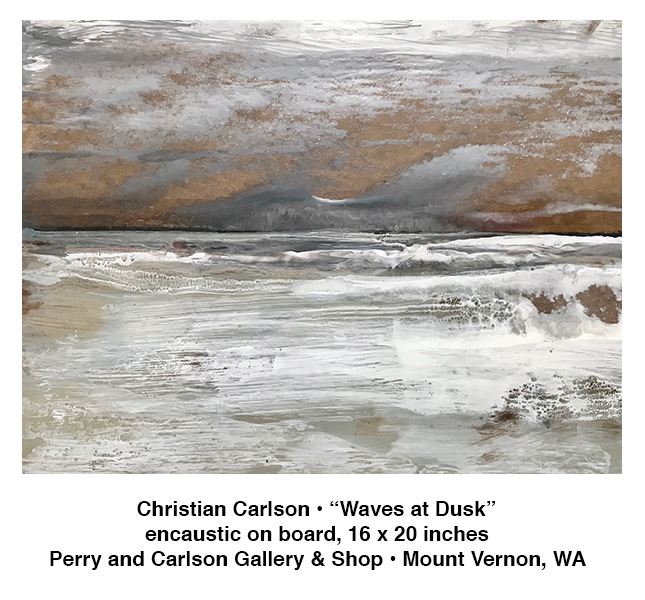

Once settled in town, “I kept noticing how the horizon organizes everything that you see, especially in the Valley where you pull over to the side of the road and there’s a field that starts right in front of you and goes almost to the horizon. And then there’s stuff on the horizon, trees, buildings, telephone poles, whatever, and then usually a uniform white sky. And so it ends up being this very abstract composition. And so I started really focusing on the line of the horizon. I would just sketch this again and again, and then I started painting it.”

His fascination continues. “I’m just obsessed with it. I can’t stop. I paint the Valley again and again and again.” Christian’s Valley-inspired work is on display in the gallery through January 31. Entitled “Skagit Winter,” the show includes drawings and paintings in encaustic, acrylic, and oil.

Clare McLean

Writer Clare McLean is based in Snohomish County.

“Skagit Winter” featuring paintings and drawings by Christian Carlson is on view Monday, Wednesday through Saturday from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. and Sunday from noon to 4 P.M. through January 31 at Perry and Carlson located at 504 South 1st Street in Mount Vernon, Washington. For more information, visit www.perryandcarlson.com.