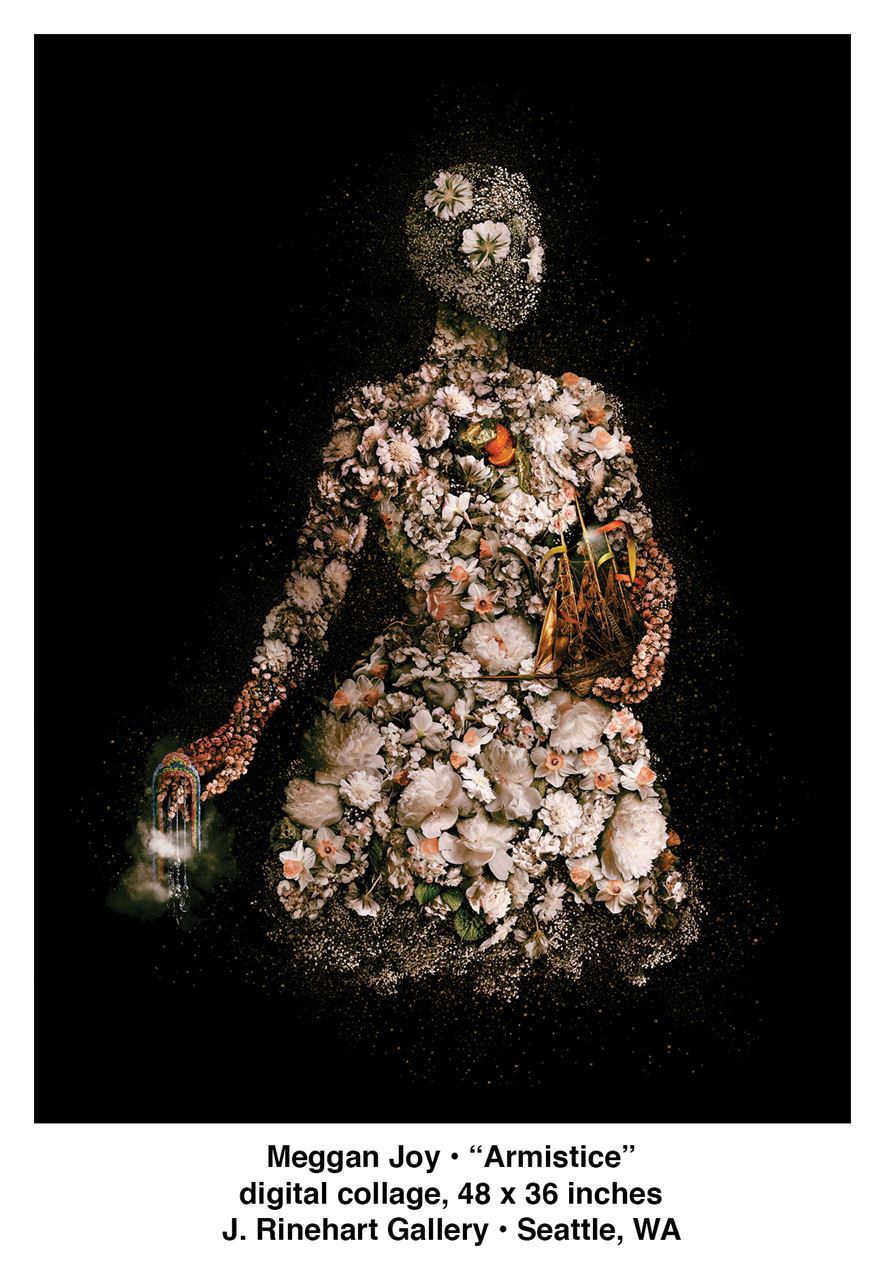

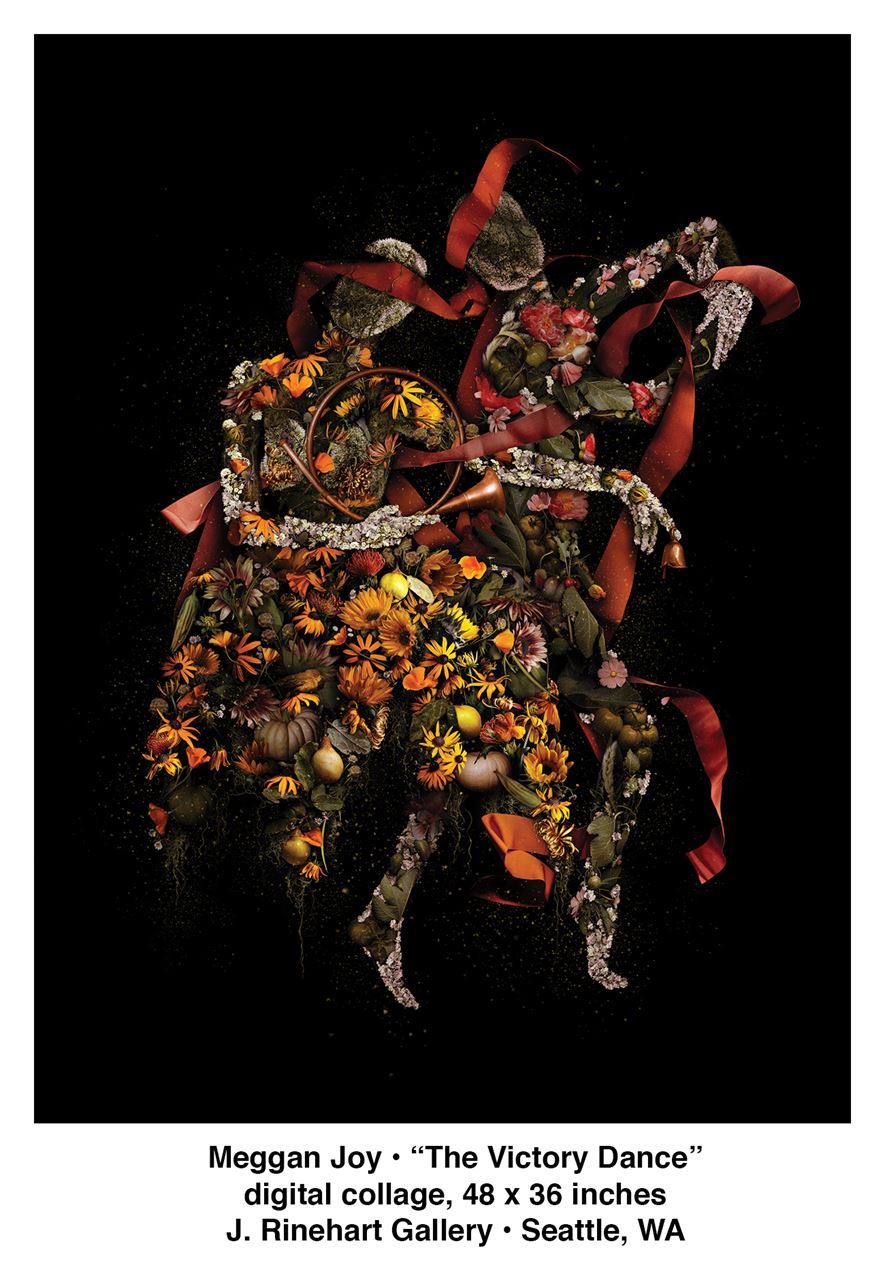

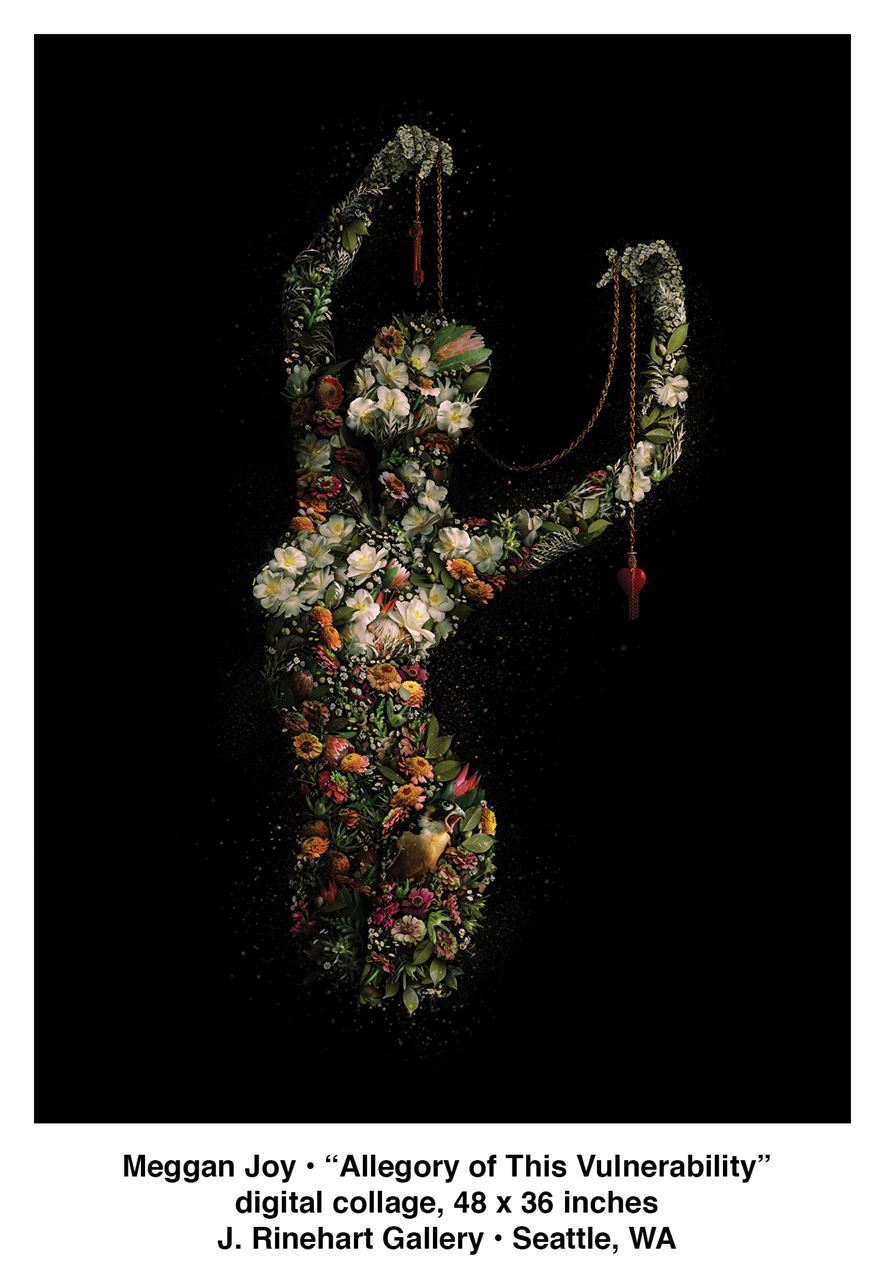

Meggan Joy grew up in Puyallup in the 1990s, the daughter of a truck driver and a homemaker. Today, she lives, gardens, and creates complex digital collage work in Seattle. Her solo show, “Battle Cry,” runs at J. Rinehart Gallery from June 13th through July 25th and features new imagery that teems with flowers, birds, insects, and more.

These aren’t just exquisite pictures. Rich with allegory and art history references, the work testifies to the resilience of women and nature’s plenitude. The few non-living objects in the images are items that Joy has repurposed from thrift shops and the like. As a stalwart recycler who aims to tread lightly, she doesn’t buy anything new other than printing supplies to create her work.

These aren’t just exquisite pictures. Rich with allegory and art history references, the work testifies to the resilience of women and nature’s plenitude. The few non-living objects in the images are items that Joy has repurposed from thrift shops and the like. As a stalwart recycler who aims to tread lightly, she doesn’t buy anything new other than printing supplies to create her work.

Joy grows many of the plants seen in her work in her Interbay neighborhood P-Patch. She also raises some of the insects in her home. “If you have to hurt another living being to make your artwork, then what’s the point of making artwork?,” she asks. “I’m not going to harm another animal for the sake of making art. When I find an insect, I will photograph them usually in place. I won’t take them out of their environment, if possible. If I can do that safely, then I will take them home really quickly and then put them right back in their same spot. But I do have a rule that I’m not gonna hold onto an insect that I found for longer than 12 hours.”

Below are excerpts from a wide ranging Zoom conversation with Joy (who has auto-immune issues) during the COVID-19 stay-at-home period; they have been edited for clarity and concision.

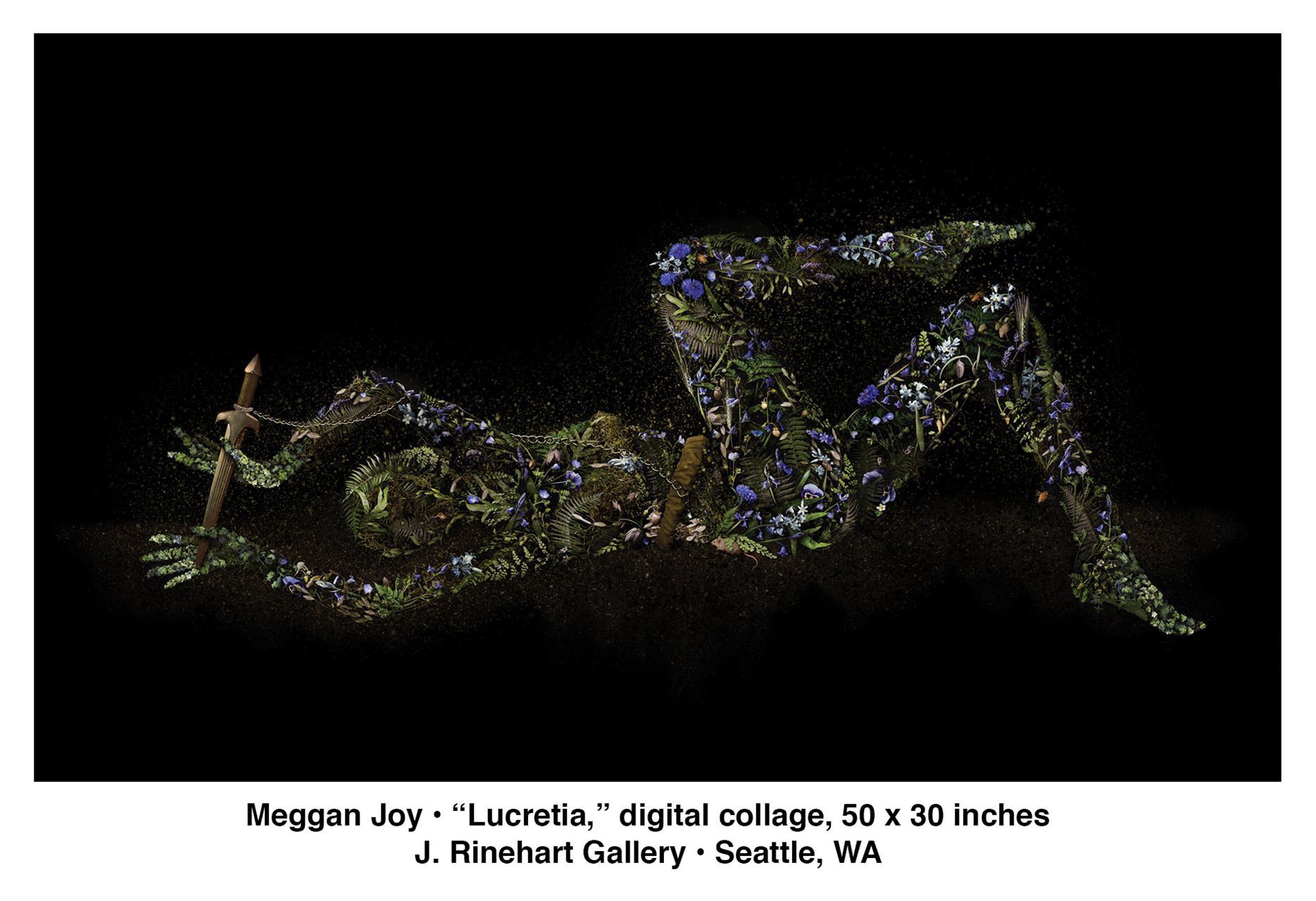

A Modern Lucretia

When I started planning the show a year ago, I was thinking, “Oh, election year.” This was when Christine Blasey Ford was in the news and all of those things. And I was thinking, “Oh, ‘Battle Cry’ will be about winners, losers, and aristocratic-type portraits.” And now we’re in this entirely different battle (the COVID-19 crisis) that nobody could have predicted.

When I started planning the show a year ago, I was thinking, “Oh, election year.” This was when Christine Blasey Ford was in the news and all of those things. And I was thinking, “Oh, ‘Battle Cry’ will be about winners, losers, and aristocratic-type portraits.” And now we’re in this entirely different battle (the COVID-19 crisis) that nobody could have predicted.

For my “Lucretia”* piece, I pulled part of the Christine Blasey Ford “I pledge” hand from that really famous image. So that’s part of her. I just kept on thinking of Lucretia when I was watching her at that time. It struck me as like, “Oh that’s a modern Lucretia—that’s who that is.” And that’s really what inspired the show.

*Lucretia has been the subject of many revered Old Master paintings. She was a virtuous noblewoman who was raped by the son of a tyrannical ruler in the sixth century B.C. Her resulting suicide caused a revolt that led to the overthrow of monarchical tyranny and the creation of the Roman Republic.

Under the Magnifying Glass

We always put magnifying glasses next to my work so that people can get really into it. I have to put glass over the front because there’s always—every night—fingerprints that we have to clean off, because people can’t help it...they’ll spend a really long time getting so close that they’re not even really seeing the human shape anymore. They’re just finding the little snails or the butterfly or the flower that they’ve never seen before. The teeny tiny strawberries, which are like my favorite to hide into things.

I think that’s why people like having the work around them…and why thankfully people are buying it because they know that they can look at it for a year or so before they can even get close to seeing everything that’s in there.

Breaking Cycles

I wasn’t even willing to consider or call myself an artist until fairly recently. I had won awards for being an artist before I felt comfortable being called an artist. I had this block that, “This isn’t for people like me, that’s for rich people. That’s not for people that grew up in trailers.”

I wasn’t even willing to consider or call myself an artist until fairly recently. I had won awards for being an artist before I felt comfortable being called an artist. I had this block that, “This isn’t for people like me, that’s for rich people. That’s not for people that grew up in trailers.”

Now that I’m a little bit on the inside (of the art world), I’m so thankful that I’m working with (gallery owner) Judith who works really hard to make an open environment that feels like a living room.

I fully intend on breaking a lot of these cycles of needing to have money to be an artist. One of the things I really want to work on is making a frame library so that artists that have an opportunity to show but can’t afford to frame the work can just rent frames for free.

Art should be democratized. I hope that from growing up very poor as a truck driver’s daughter, coming at this from a very outside perspective, that I can bring something different to it. I think that’s actually a responsibility of mine as somebody that’s in this space, to be honest...it’s part of my job to make sure that other people get seen equally.

Two Shout-Outs

My husband is basically my assistant that I don’t have to pay. We were on a hike, and was like, “Ooh, I found a lizard. Can you just hold onto him for a second?” And I look over and the lizard is hanging off his beard while I’m trying to set up my camera. He used to be an Army Ranger, so he’s gotten into worse situations than I could ever get him into.

I am the person everyone is staying home to protect. I would be risking my life to go out and print right now because of my auto-immune issues. I don’t know how we could have done this show without the Photo Center and Sandy King. She’s the digital lab lead there and I call her my hero—she’s been doing all the printing for the show. She knows how picky I am and she holds the same standards I do. The execution has to be spot-on because it’s on a black background.

Flower Anarchy

If we’re able to have an opening, I’m giving everybody little May Day baskets with flowers or flower seeds. Hopefully people will be planting flowers all around the city. It’s a total experiment of like, can I get this to happen? Is planting wild flowers the same thing as graffiti? Is it considered a nuisance or is it considered artwork? Let’s see…

Clare McLean

Clare McLean is a writer, photographer, and horticulture student in Snohomish County.

The opening reception is on Saturday, June 13th, from 3-6 P.M. and First Thursday, July 2nd, from 5-8 P.M. J. Rinehart Gallery is located at 319 Third Avenue South in Seattle, Washington. For information, visit www.jrinehartgallery.com.