Seattle Asian Art Museum: Reimagined. Reinstalled. Reopened.

Visit the dazzling new installations at the Seattle Asian Art Museum as soon as possible! In a striking departure from tradition, the museum is now organized thematically rather than by geography, the only Asian Museum in the country to take this bold step. It is a huge success.

Themes enable us to see familiar works with new eyes, and to enjoy never before seen masterpieces. Each theme includes many countries, and each object often is the result of crossing boundaries, such as a Chinese robe made with Russian silk.

As you explore the twelve themes, enjoy the cultural intersections. In fact, the theme of the entire museum is the intersections of culture.

As you explore the twelve themes, enjoy the cultural intersections. In fact, the theme of the entire museum is the intersections of culture.

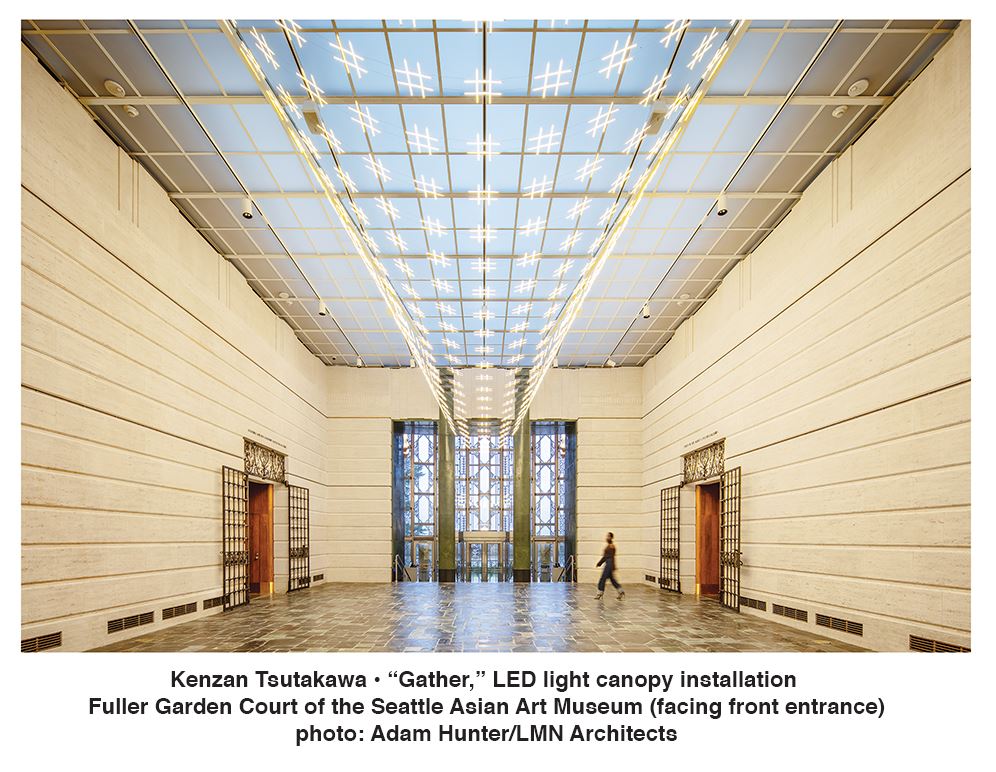

Architectural firm LMN restored the stunning 1933 Art Deco building. As you approach the entrance, you at once notice that it glows a subtle pink color as a result of the restoration of the exterior. The reglazing of the doors now allow views out to the park and beyond. Restored windows throughout the museum allow frequent views of Volunteer Park and its magnificent trees.

The new gallery of over 2600 square feet is scaled to the rest of the building. In addition there are newly imagined education spaces and a state-of-the-art lab for restoring the mounting of Asian painting, the only one west of the Mississippi. Even the auditorium has new seats (made by the original firm) and better lines of sight.

First look up at the delicate canopy in the Fuller Garden Court by Kenzan Tsutakawa, the grandson of our famous George Tsutakawa. Composed of LED lights in a pattern based on Asian textiles, it swoops toward the front door and the outside world.

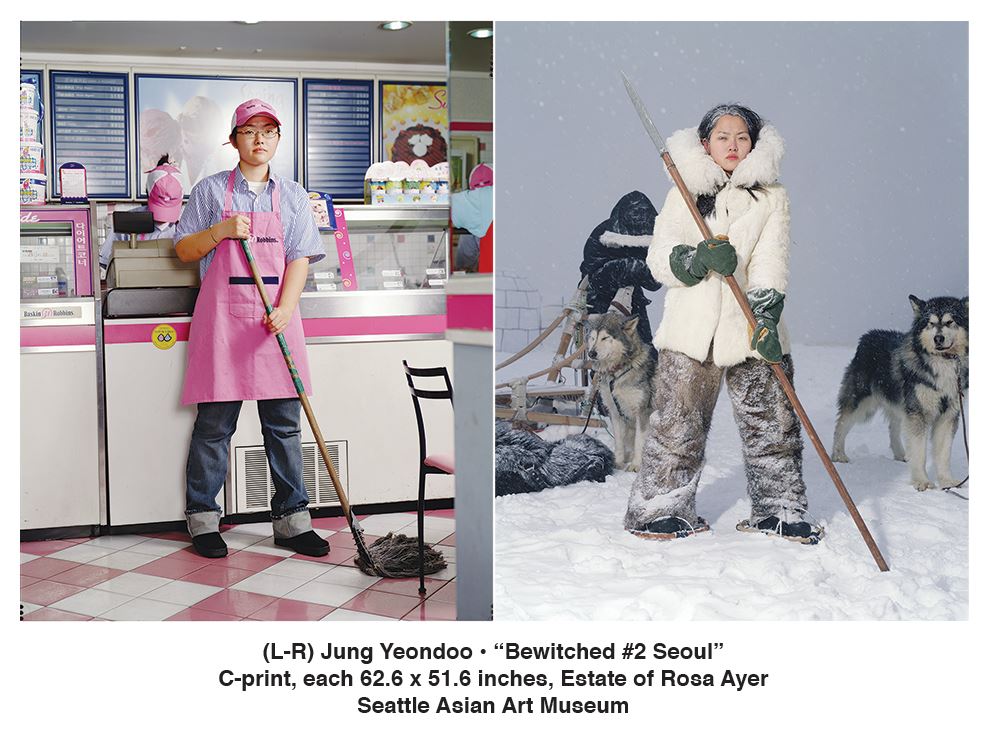

Many works have never been shown before such as a Filipino “Fichu” or shawl, made of pineapple fiber in the first gallery off the Fuller Garden Court titled “Are We What We Wear?” In another radical act, the curators added contemporary work in most of the galleries, amplifying their themes. So in this gallery we see jewelry and ceremonial clothing, along with contemporary Korean photographer Jung Yeondoo’s “Bewitched” project. The two photographs pair a young woman dressed for her humble job with the same woman outfitted for her fantasy life to explore the Arctic.

Many works have never been shown before such as a Filipino “Fichu” or shawl, made of pineapple fiber in the first gallery off the Fuller Garden Court titled “Are We What We Wear?” In another radical act, the curators added contemporary work in most of the galleries, amplifying their themes. So in this gallery we see jewelry and ceremonial clothing, along with contemporary Korean photographer Jung Yeondoo’s “Bewitched” project. The two photographs pair a young woman dressed for her humble job with the same woman outfitted for her fantasy life to explore the Arctic.

“Writing Images” includes painting, calligraphy, and poetry. Don’t miss the small horizontal book made of stacked palm fronds, then enjoy the larger masterpieces. These fragile light sensitive works most likely are to be on display for only six months.

The narrow gallery, “Color in Clay,” faces the park with a long display ranging from white to polychrome. It has no labels which encourages simply looking at the colors as they change according to the light. A video display includes all the information about each piece if we want to pursue the detail.

Just to the right of the front entrance, “Kamadeva, God of Desire” greets us in “Spiritual Journeys.” Highlighted here as an outstanding 12th century masterpiece of the South Asian Collection, it was formerly lost in the many works in the Fuller Garden Court. After exploring the images of gods of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam, pause in the next gallery, “Awakened Ones,” and listen to chants: these three Buddhas are from Japan, China, and Thailand.

“Divine Bodies” emphasizes the human body, accompanied by a video that outlines “mudras,” the complex blessing gestures of Buddhism. We can see a teaching gesture in the early 9th century bronze of Buddha Shakyamuni. This bronze is so sensitive to oxygen that it required a special case and has never been displayed before. Anita Dube’s photographs “Offering” of ceramic eyes on hands creating mudras hangs above a riveting thousand armed eleven headed Guanyin. Dube’s work is one of many contemporary works loaned by our generous local collectors Sanjay Parthasarathy and Malini Balakrishnan.

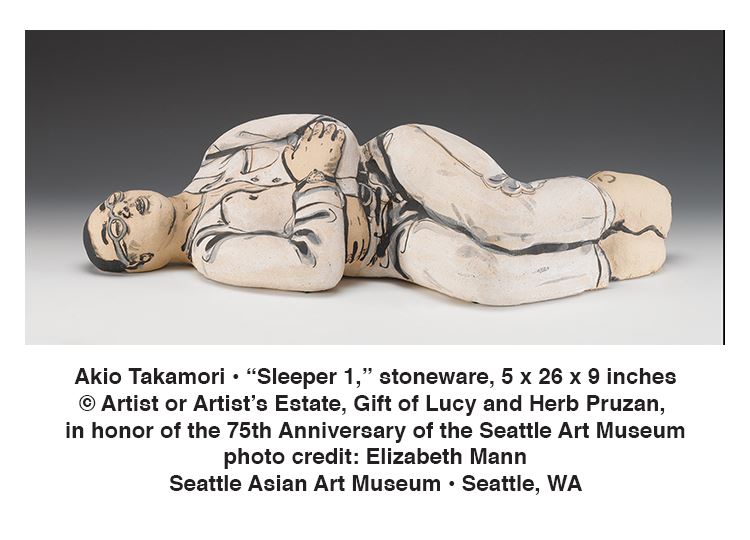

Finally the new gallery has a separate contemporary art exhibit, “Belonging,” centered around the enormous and familiar Do Ho Suh’s “Some/One,” made of hundreds of military dog tags. In addition to international superstars, be sure to find the work of our own Akio Takamori. His group of poignant ceramic figures depict villagers he remembered from his childhood in Japan.

As you leave the large new space, pause with Kim Soja’s “Mandala: Zone of Zero,” three “mandalas” made from juke boxes, each reciting a different chant from Gregorian, Islamic, and Buddhism, an example of ecumenism so crucial in today’s world.

Perfect. Hats off to the curators and the staff.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com and for local, national, and international publications.

The Seattle Asian Art Museum, located at 1400 E. Prospect Street in Seattle, is open Wednesday from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M., Thursday from 10 A.M. to 9 P.M., Friday from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M., Saturday from 9 A.M. to 5 P.M., and Sunday from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. For info, visit www.seattleartmuseum.org/visit/asian-art-museum.