On a quick road trip from Bainbridge Island to Roslyn, I had the pleasure of visiting the studio and darkroom of Glenn Rudolph. As we sat on the deck and drank almost too much coffee, we geeked-out on old school shoptalk; films and their processing, 50 year old medium format cameras, optical qualities of German lenses, and where all roads photographic lead, to the Light.

On a quick road trip from Bainbridge Island to Roslyn, I had the pleasure of visiting the studio and darkroom of Glenn Rudolph. As we sat on the deck and drank almost too much coffee, we geeked-out on old school shoptalk; films and their processing, 50 year old medium format cameras, optical qualities of German lenses, and where all roads photographic lead, to the Light.

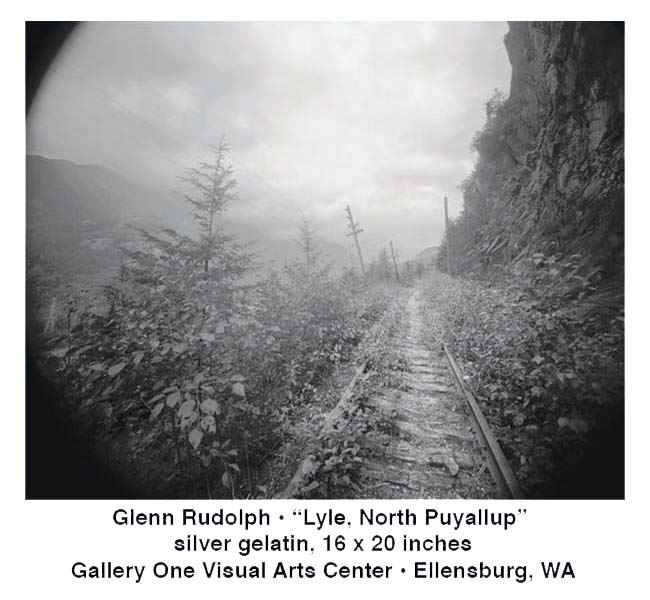

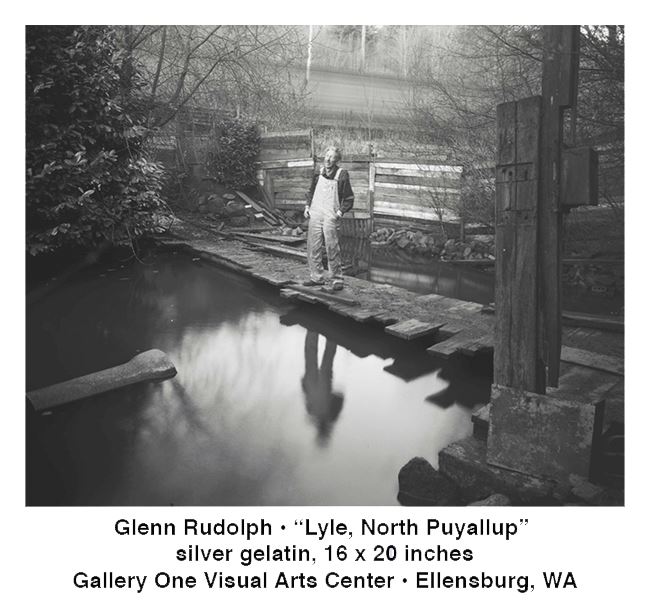

“I’ve always been fascinated by the transitional light of the Northwest climate. Combining this with real-life props makes the world an interesting place to work,” said Rudolph.

His work is non-fiction, close in spirit to documentary film, but he conjures much more than the facts. “I feel like I am still part of the WPA photo project from the thirties, with a twist of Constable, Turner, Ryder, Blake, Giorgioni, Titian, and the entire history of Western painting mixed in.”

And then we moved from the deck to the workspace to look at the series of images headed to an exhibit at Gallery One in Ellensburg, “Are We There Yet?”

Rudolph began photographing the Milwaukee Railroad about 30 years ago. The Milwaukee was the last transcontinental railroad to reach the West Coast in 1908. The western division was torn out and sold for scrap in 1980. “I was curious where it ran. It had a distinct look with its trolley poles marching all the way to Harlowton, Montana.”

Describing his work, Gallery One Executive Director Monica Miller states “Using light as his primary medium, Glenn has captured the story of the disappearing railroad and the people and objects that coexist with the spaces left behind.”

These days Rudolph is more likely to run into mountain bikers than hobos when he and his wife walk the grade near Cabin Creek or Beverly. The biker’s eyes widen when he gives them a short history of where they are riding. These incredible images are sure to open your eyes to that history too, making your next hike or road trip in the area that more meaningful.

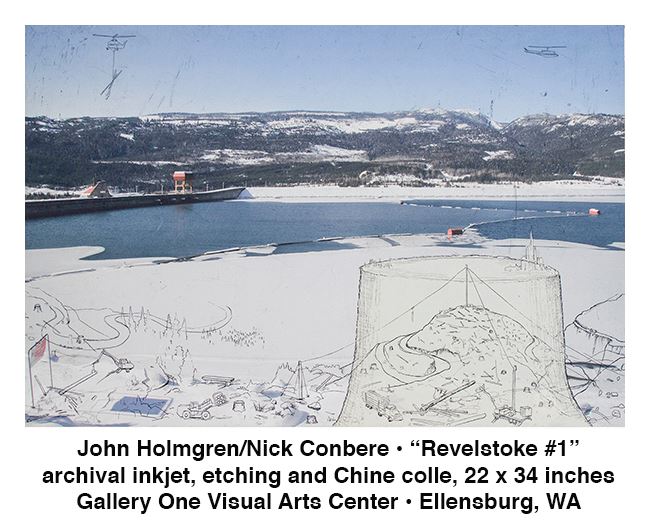

John Holmgren’s body of work uses rivers and man-made structures to highlight boundaries. Through his photo-montages we rediscover our relationship with the natural environment. We are taken on an expedition to somewhere, sometimes unidentifiable yet always defined.

John Holmgren’s body of work uses rivers and man-made structures to highlight boundaries. Through his photo-montages we rediscover our relationship with the natural environment. We are taken on an expedition to somewhere, sometimes unidentifiable yet always defined.

In collaboration for the past two years with Nick Conbere, “River Relations: A Beholder’s Share of the Columbia River Dams” investigates the presence and impact of hydro-electric dams on the Columbia River. They ask how aesthetic relationships can offer compelling ways to consider human construction that alter natural forces, re-shaping the flow of a river.

I asked about their influencesin this layered/collaborative approach. Holmgren stated, “We are inspired by a variety of past works that interpret landscape and experience, ranging from 19th century Romanticist paintings to documentary photography and historic cartography. Our collaboration documentation and interpretation aims to explore parallels among various places and histories along the river, suggesting patterns and relationships, and facilitating documentary, metaphor, and allegory in considering the presence of the dam.”

Holmgren takes the photographs and Conbere adds the drawings, line, and language. This is a fascinating approach to multi-layered, narrative work. Two artists, collaborating in different mediums, on the same page.

Not surprisingly when I asked him if he had any particular affinities with contemporary artists he said, “Robert Rauschenberg and Mark Klett,” while emphasizing that he was more influenced by writings about water and the sciences.

The works of Glenn Rudolph and John Holmgren/Nick Conbere give new ways to enter into the history and geology of our region.

Upstairs in the Eveleth Green Gallery, a group show of travel photography includes local and international sites taken by photographers from this region including Nick Bosso, Styler Crady, Lynn Harrison, Chris Heard, Philippe Kim, Ona Solberg, and Laura Stanley.

Chris Heard and I had something in common, we both studied with Henry Wessel Jr. “He taught me so much about photography, yet encouraged me to do my own thing which was, and always has been, more landscape oriented,” said Heard. He kept his approach to the landscape very simple with 35mm black and white film, then interpreting what he sees through digital processing and printmaking, using fine art papers and glazes. “As I create my prints, I am more in mindof the drawings of Georges Seurat and traditions of mezzotint prints than I am in the process of traditional photographic imaging.”

A drive to Ellensburg to see “Are We There Yet?,” most likely is sure to lead to many more road trips with fresh eyes on Washington State history and geology.

Joel Sackett

Joel Sackett is a photographer and writer living and working in the Northwest.

“Are We There Yet?” is on view through July 30, Monday through Friday from 11 A.M. to 5 P.M. Saturday from 11 A.M. to 4 P.M., and Sunday from noon to 4 P.M. at the Gallery One Visual Arts Center, located at 408 N Pearl Street in Ellensburg, Washington. For more information, visit www.gallery-one.org.