Tabaimo: Utsutsushi utsushi at the Asian Art Museum in Seattle, Washington

The fascinating exhibition by the world renowned artist Tabaimo at the Asian Art Museum tells us that the world is not what it seems. Behind mundane objects, in a clothing chest, in a toilet, in a bedroom, lurk other forces, other realities, other creatures, even escape to magic spaces.

The fascinating exhibition by the world renowned artist Tabaimo at the Asian Art Museum tells us that the world is not what it seems. Behind mundane objects, in a clothing chest, in a toilet, in a bedroom, lurk other forces, other realities, other creatures, even escape to magic spaces.

The exhibition, which the artist also curated, includes four new videos that respond to works in the Asian Art Museum’s permanent collection. Tabaimo invented the tricky title of her show, “Utsutsushi utsushi” based on the underlying idea of “utsushi” copying or studying a master artist’s work in order to not only understand it, but to grasp its deeper spiritual meaning, to connect across time to it and to honor it. She has turned the concept into an active verb, as becomes clear in viewing the exhibition. She does not just explore the style of the historic master works that she chose for the exhibition, she expands on them, imagining a narrative that takes place inside or beside, or above or below them.

Tabaimo’s work perfectly suits the present moment: uncertain, unsteady, unsafe, unpredictable, but it is also deeply poetic. The artist began by paying homage to her mother, Tabata Shion, a ceramic artist, who inspired the unusual title of the exhibition. Tabaimo’s mother practices “utsushi” as a ceramic artist. The exhibition begins with her work juxtaposed to her master, the artist Ogata Kenzan from the Edo period in Japan.

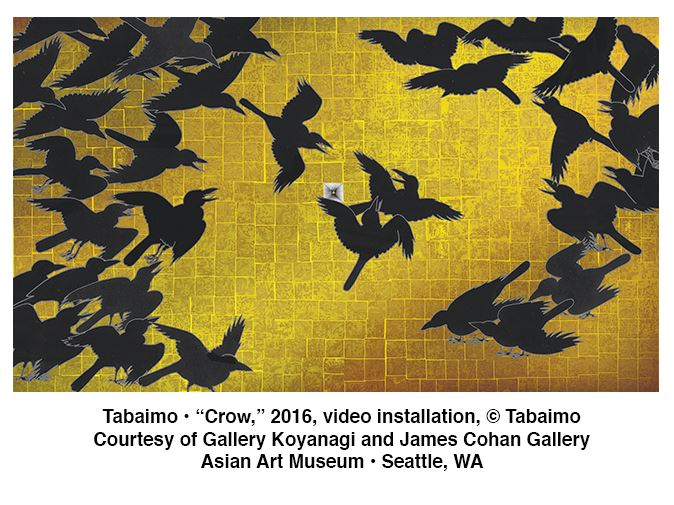

Tabaimo practiced her own “utsutsushi“ with specific historical works in the collection of the Asian Art Museum, all of which are included in the exhibition. The most straightforward example, and perhaps the thematic heart of the exhibition (although it appears in the last gallery), is Tabaimo’s video in response to the Museum’s unique early seventeenth century six part panel “Crows.” The original awes us with its brilliantly conceived “murder” of crows (as a group of crows is called). The artist discovered that the crows were so subtly drawn, that she actually had to trace them for her own work, “Crow.” In her video a gold wall opens up into a receding space, as crows fly into it, or land above it. But crows also pop up, and fly into several of the other works in the exhibition. You can look out for them.

For another “utsutsushi” her point of departure are two hanging scrolls of “Dragonflies” and “Butterflies,” detailed naturalistic ink drawings and verses, the result of collaboration among over 70 late Edo artists. Tabaimo “liberated” the dragonflies and butterflies in her video, formatted like the scrolls. Now they fly free and disappear from view. But she explored the original work carefully as she recreated the creatures.

For another “utsutsushi” her point of departure are two hanging scrolls of “Dragonflies” and “Butterflies,” detailed naturalistic ink drawings and verses, the result of collaboration among over 70 late Edo artists. Tabaimo “liberated” the dragonflies and butterflies in her video, formatted like the scrolls. Now they fly free and disappear from view. But she explored the original work carefully as she recreated the creatures.

At the beginning of the exhibition, she pairs two 16th century Chinese wooden chests and a video called “Two,” 2016, which appears on the back of a transparent wall behind the chests, so that their silhouette frames the video. Here we see what I referred to in the beginning, the forces lurking behind the mundane. Initially we see a chest full of bed covers, but then an arm reaches out from a pillow! And it goes on from there. I won’t spoil the experience with too much detail.

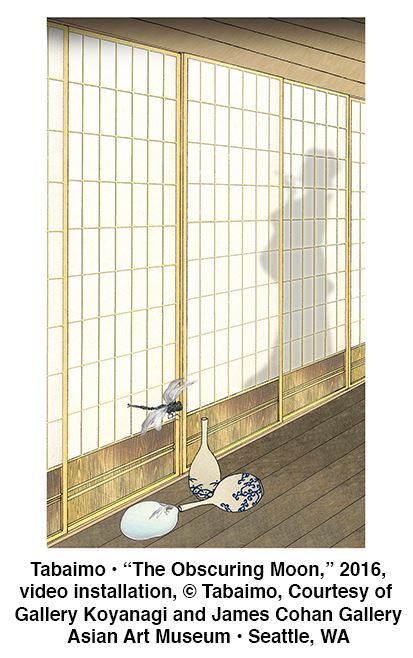

“The Obscuring Moon” develops a narrative for a shadowy woman who barely appears behind a screen in an original print by Hiroshige. Tabaimo places her in the center of an elusive story. But she carefully emulates Hiroshige’s colors, and we are treated to a roomful of his prints in order to enjoy that connection.

Another reference to women is “aitaisei-josei,” a story of suicide, based on a seventeenth century story and a modern novel, “Villain,” by Yoshida Shuichi. Tabaimo creates connections between Ohatsu and Kaneko Miho, the main female characters of the two books, through metaphor and symbolism.

Among the pre-existing work, each surprises us in a different way. Most amusing is the “Public ConVENience,” 2006, a three walled walk in with projections of life size Japanese public toilets. The characters come and go with many unexpected actions.

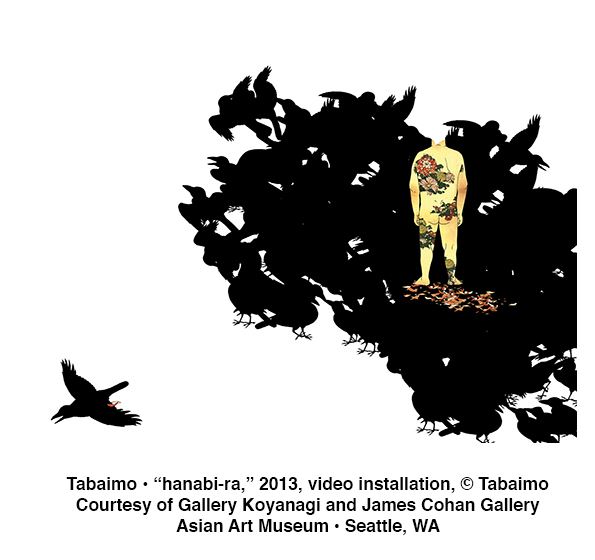

“Hanabi-ra” gives us what appears to be a representation of a man covered in flowered tattoos and “haunted house,” on loan from the Asia Society, is a large screen city scape with unpredictable scale shifts, and narrative jolts. Tabaimo utsushi’d the spirit of the voyeuristic aerial cityscape from a 17th century Japanese painting that details the daily lives of city dwellers. We see the original example in the next room.

This exhibition is another Asian Art Museum coup, a cutting edge artist in our wonderful “other” museum in Volunteer Park. Just to give you an idea of Tabaimo’s status, she represented Japan in 2011, at the Venice Biennale, and her work is in the collection of Asia Society in New York.

Don’t fail to go, as the Asian Art Museum will be closing when it is over, for two years of remodeling and expansion, its first real remodel since it was built in 1933.

Susan Noyes Platt, Ph.D.

Susan Noyes Platt, Ph.D. is an art historian, art critic, curator, and activist. She continues to address politically engaged art on her blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com.

“Tabaimo: Utsutsushi utsushi” is on view through February 26, Wednesday and Friday-Sunday, 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. and Thursday from 10 A.M. to 9 P.M. at the Asian Art Museum, located in Volunteer Park at 1400 East Prospect Street in Seattle, Washington. For more information, visit www.seattleartmuseum.org/visit/asian-art-museum.