Artists collectives are truly a great boon to our art scene, especially when grass roots collectives reach out to support each other.

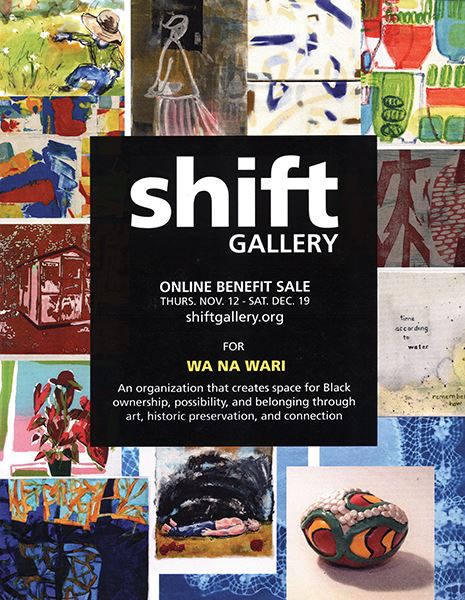

Such is happening in November when the long established artist-run space Shift Gallery is reaching out with an online benefit sale to support the much more recently established Central District black cultural center Wa Na Wari.

Wa Na Wari describes itself as a “center for Black art, stories and connection in Seattle’s Central District. This Central District home owned by a black family for five generations, continues to be a legacy of kinship and community building.” As you enter the house we read that it encourages the community to be part of the process of “preservation, reclamation and celebration.”

Wa Na Wari describes itself as a “center for Black art, stories and connection in Seattle’s Central District. This Central District home owned by a black family for five generations, continues to be a legacy of kinship and community building.” As you enter the house we read that it encourages the community to be part of the process of “preservation, reclamation and celebration.”

Wa Na Wari plays a crucial role in Seattle. As the home of founder Inye Wokoma’s grandmother, it has a long history with his extended family. Wokoma’s innovative multi media creations based on film and photography offer us his personal family history as well as that of the Central District where he has lived all his life.

He decided to save his grandmother’s home at 911 - 24th Avenue from the ravages of gentrification (he lives in another home owned by his family next door). With a team of three other people, Elisheba Johnson, Jill Freidberg, and Rachel Kessler, Wa Na Wari (meaning “our home” in the Kalabari language of Southern Nigeria), presents black artists in many media. It holds workshops, films, readings, lectures, fashion shows, and art exhibitions. It also collects oral histories from residents and former residents of the Central District. You can listen to them on an old fashioned telephone.

The curator Elisheba Johnson brilliantly presents visual art exhibits that create a synergistic energy suited to the spirit of the house. Every exhibit is sophisticated and provocative combining artists from the Northwest with those living elsewhere, youthful emerging artists and established professionals.

Looking at the current exhibition, the four artists intersect both emotionally and spiritually with each other, with us and with the house. Each room/gallery is small and devoted to one artist, making it possible to dive in deep and really experience their work.

As we enter the former living room dining room area, now called Wilson Hall, the large gallery shows the work of Zahyr Lauren, also known as The Artist L.Haz. His woven cotton blankets based on a meditative process speaks through sacred geometry and symbols to suggest “Black pride, power, and regality, alongside pain and grief.” We feel their almost magical presence as we move through the space. Particularly overwhelming is the work, appropriately hung over the fireplace, with the title “The Door of No Return.”

As we enter the former living room dining room area, now called Wilson Hall, the large gallery shows the work of Zahyr Lauren, also known as The Artist L.Haz. His woven cotton blankets based on a meditative process speaks through sacred geometry and symbols to suggest “Black pride, power, and regality, alongside pain and grief.” We feel their almost magical presence as we move through the space. Particularly overwhelming is the work, appropriately hung over the fireplace, with the title “The Door of No Return.”

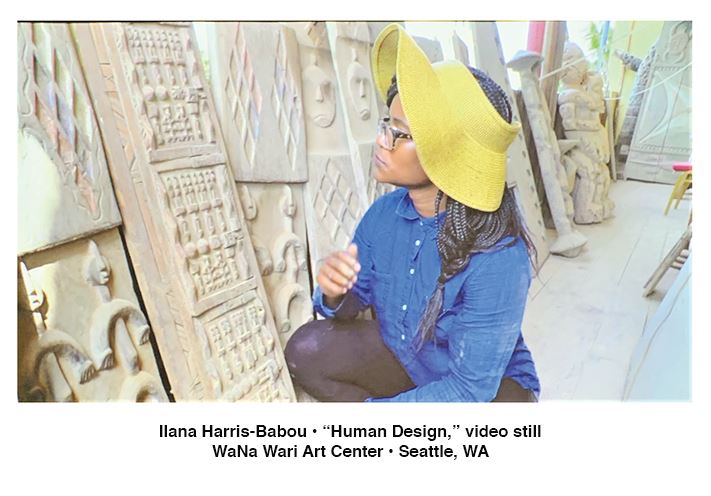

In the first gallery upstairs, Gallery Kyle, the video “Human Design” by the amazing Ilana Harris-Babou requires several viewings to fully appreciate her sincerity paired with parody. Her work explores the absurdities of consumer culture, in this case looking at what she calls “the white washing” of culture from Africa. She takes us on a tour of various sites in Senegal, her own country of origin, as she presents the steps to understanding the real sources of the art work in upscale design stores. Her final visit is to the place from which slaves were shipped now, a museum, “Maison des Esclaves.” This piece is a great choice for Wa Na Wari. Other works by the artist parody cooking shows, make over advice, and other themes. She is humorous and biting at the same time.

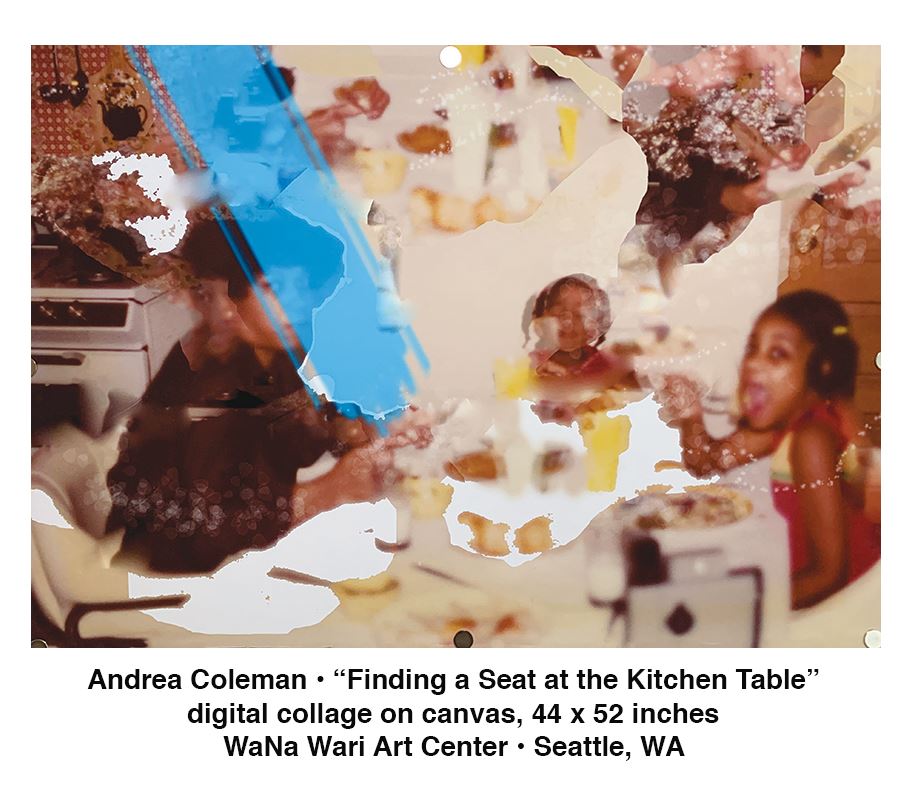

In a second room, Gallery Birdie, Andrea Coleman’s digital artworks combine old photographs and abstraction. The haunting family photographs emerge from layers of browns and blues and yellows. In “Finding a Seat at the Kitchen Table,” 2017, we see the old photograph capturing an ordinary moment with family that resonates with many layers of references, even as we simply appreciate the artist’s aesthetic subtlety.

Finally, the work of Zachary James Watkins “Listen to Clarence” combines archival footage of the Civil Rights March on Selma, brilliantly edited to encompass all the different perspectives on the march, including the participants, young children, the police, and white nationalists holding confederate flags.

The video is paired with a recording of Watkins sound/video piece “Listen to Clarence” which includes an interview with Dr. Clarence B. Jones, Martin Luther King’s speech writer, describing the “I have a dream” speech, along with Watkins’ haunting sonic work “Peace Be Til” a commission with the Kronos Quartet.

Together these works all provide a spiritual and emotional journey through time and space, through history and the present.

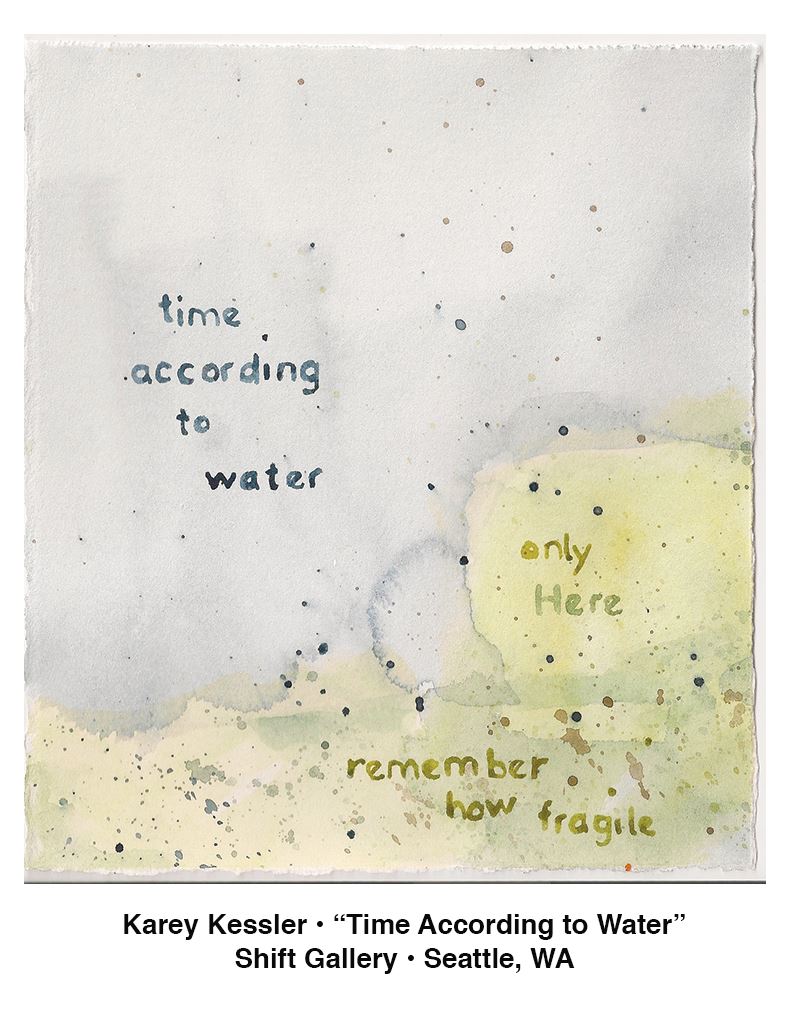

The Shift Gallery is also a special space that makes a perfect partner to Wa Na Wari. The Shift Gallery artists explained their sense of community, collaboration, mutual support, and collective spirit. They share all the responsibilities of running the gallery on a volunteer basis, from producing a professional publication to installing exhibitions.

The Shift Gallery is also a special space that makes a perfect partner to Wa Na Wari. The Shift Gallery artists explained their sense of community, collaboration, mutual support, and collective spirit. They share all the responsibilities of running the gallery on a volunteer basis, from producing a professional publication to installing exhibitions.

Shift Gallery’s support of Wa Na Wari is through an online benefit sale at www.shiftgallery.org from November 12 through December 19. Twenty artists have contributed a work worth $200 or less. All the sale proceeds go to Wa Na Wari.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com and for local, national, and international publications.

Wa Na Wari, located at 911 - 24th Avenue in Seattle, Washington, is open Fridays from 2 to 8 P.M. and Saturdays and Sundays from 11 A.M. to 5 P.M. For more information, visit www.wanawari.org.

Shift Gallery, located at 312 South Washington Street in Seattle, Washington, is open Friday through Saturday from 12 to 5 P.M., and by appointment. For more information, visit www.shiftgallery.org.