We are so fortunate to have “Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem” at the Frye Art Museum (until August 15). Delayed for a year by the pandemic, we can now enjoy this selection of world-class artworks from The Studio Museum in Harlem’s outstanding collection. Founded in the watershed year of 1968 by artists, activists, and philanthropists, The Studio Museum’s mission is to provide a place for “artists of African descent locally, nationally, and internationally.” It has long been an anchor of culture of the African diaspora, led by a succession of dynamic curators and directors.

We are so fortunate to have “Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem” at the Frye Art Museum (until August 15). Delayed for a year by the pandemic, we can now enjoy this selection of world-class artworks from The Studio Museum in Harlem’s outstanding collection. Founded in the watershed year of 1968 by artists, activists, and philanthropists, The Studio Museum’s mission is to provide a place for “artists of African descent locally, nationally, and internationally.” It has long been an anchor of culture of the African diaspora, led by a succession of dynamic curators and directors.

In the first gallery a selection of work by the Founders of the museum introduces the range of approaches seen in “Black Refractions:” realism in Jacob Lawrence, figurative collage by Romare Bearden, and abstraction by Norman Lewis. His Blue and Boogie, named after a famous jazz piece by Dizzie Gillepsie and Frank Paparelli, also points to another theme that permeates the exhibition—music.

In the next gallery, Benny Andrews’ “Composition (Study for Trash)” immerses us in a strange sight: the Statue of Liberty, flaming torch aloft, crosses her legs sitting atop a globe held up by headless white man wearing only boots. In a United States shaped gap below her, men are hauling on a load we can’t see. One of many studies for the mural Trash, one panel of Andrews’ twelve-part iconic and sardonic “Bicentennial Series” of the early 1970s, it immediately tells us of both the radical attitudes of the artist, and the activist roots of The Studio Museum itself. Benny Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition in response to the Metropolitan Museum exhibition “Harlem on My Mind,” of 1968 which, astoundingly, completely excluded Black artists.

Not far away Elizabeth Catlett’s life size mahogany Mother and Child, instills immense tenderness into this familiar subject. In stark contrast, Melvin Edwards welded steel “Cotton Hangup” menacingly hangs from the ceiling nearby.

The next section, “Abstraction,“ highlights that the museum’s early years included the peak years of abstraction in the arts, and Black artists made it their own. Such well known artists as the sculptor Richard Hunt, and painters William T. Williams, Charles Alston, Sam Gilliam, and Jack Whitten dazzle us with their complexity and subtlety.

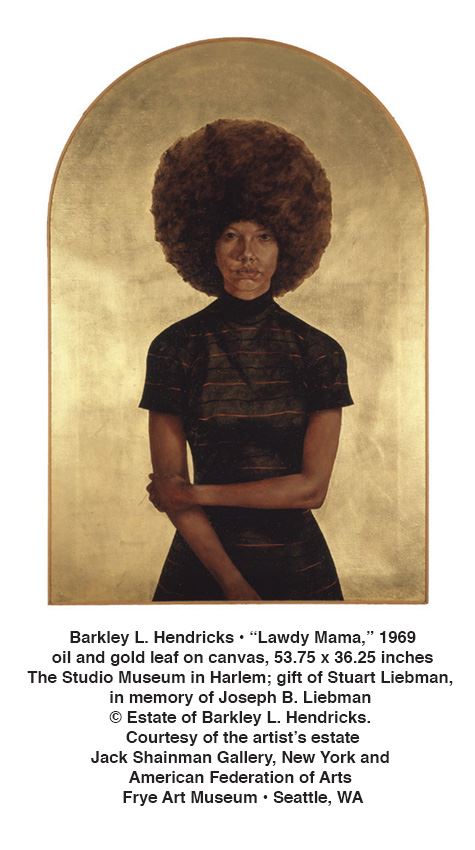

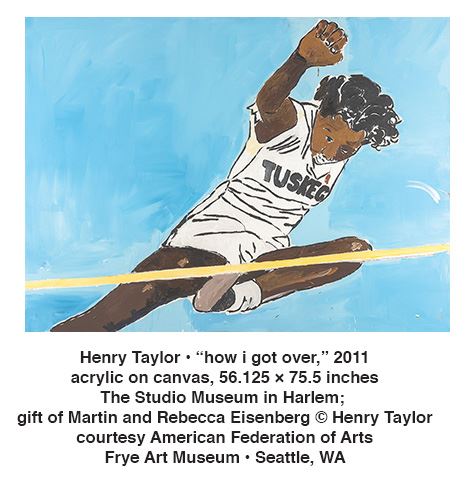

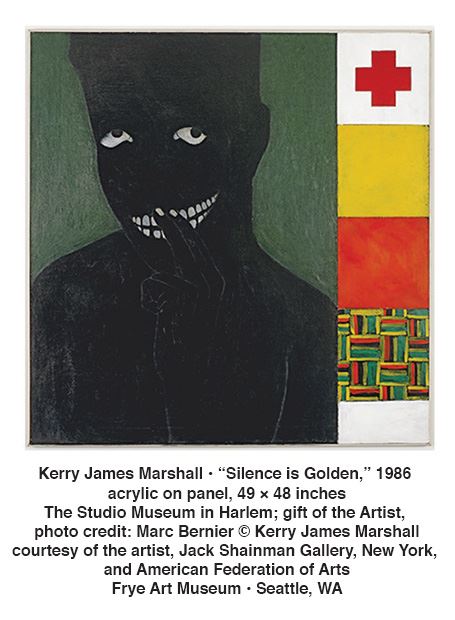

“Framing Blackness,” opens with a vivid painting by Henry Taylor of the 1948 Olympic gold medal high jumper Alice Coachman leaping over a high bar (she broke the record at five feet six and a half inches. The painting also subtly refers to overcoming barriers for all Blacks. Among other well-known artists here are Kerry James Marshall, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Barkley Hendricks and Fred Wilson.

“Framing Blackness,” opens with a vivid painting by Henry Taylor of the 1948 Olympic gold medal high jumper Alice Coachman leaping over a high bar (she broke the record at five feet six and a half inches. The painting also subtly refers to overcoming barriers for all Blacks. Among other well-known artists here are Kerry James Marshall, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Barkley Hendricks and Fred Wilson.

“Their Own Harlems” includes heavy hitters like Lorraine O’Grady, Chris Ofili, Willie Cole, Betye Saar, and Faith Ringgold. Ringgold’s early quilt, a final collaboration with her mother, celebrates the diversity of Harlem. Dawoud Bey’s small 1970s photographs of ordinary people in Harlem build on the work of the famous Harlem photographer James Van Der Zee (also included here), and lead directly to his major works today (He just had a one person exhibition at the Whitney Museum).

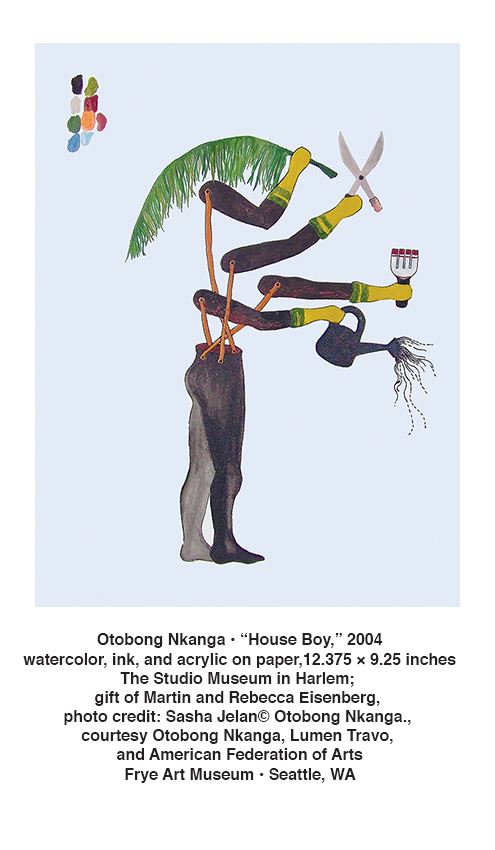

The next gallery honors a series of Studio Museum shows known as the “F” shows “Freestyle” (2001), “Frequency” (2005–06), “Flow” (2008),” Fore” (2012–13), and “Fictions” (2017–18).” Their purpose was to reach out to young artists of African and Latin American descent. The inclusion of diaspora artists emphasizes the museum’s commitment to reach into the world, even as it is embedded in its own geography. Nigerian Otobong Nkanga’s small watercolor “House Boy” of a headless child with multiple arms each pursuing a mundane chore, contains a world of references.

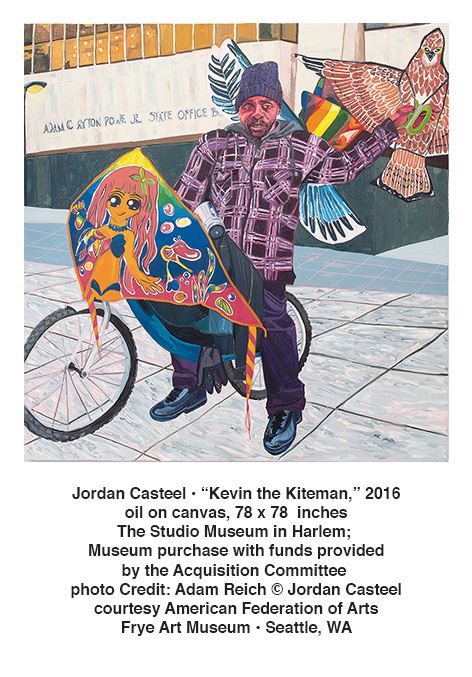

The last gallery “Artist in Residence,” features artists who have worked at the Studio Museum from the early 1970s up to the present, a concept pioneered by the abstract artist William T. Williams. The museum’s physical location in the heart of Harlem, the epicenter of Black culture for decades, led artists to simply look out the window or walk the streets for material for their paintings. One of my favorites is Jordan Casteel’s “Kevin the Kiteman.”

Many current superstars held residences at the Museum including Kehinde Wiley, Titus Kaphar and Mickalene Thomas (All of these artists have shown at the Seattle Art Museum). Chakaia Booker’s extraordinary sculpture of rubber tires evokes black hair with the double take title “Repugnant Rapunzel (Let Down Your Hair).”

The fascinatingly complex Kenyan Wangechi Mutu has a small bronze sculpture of a “nguava,” a mythical creature, and a large intricate watercolor/collage, “Magnificent Monkey-Ass Lies.”

Take a side trip to see her life-size bronze sculpture, “The NewOnes, will free Us: The Seated IV” at the University of Washington on West Stevens Way just east of 15th Avenue NE.

African American and diaspora artists have come a long way since the protests of “Harlem on My Mind.” This exhibition demonstrates the breadth, variety, and brilliance of some of those artists from The Studio Museum’s collection.

African American and diaspora artists have come a long way since the protests of “Harlem on My Mind.” This exhibition demonstrates the breadth, variety, and brilliance of some of those artists from The Studio Museum’s collection.

Don’t miss it!

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com and for local, national, and international publications.

“Black Refractions” is on view Thursday through Sunday from 11 A.M. to 5 P.M. until August 15 at the Frye Art Museum located at 704 Terry Avenue in Seattle, Washington. For more information and to reserve a timed ticket, visit www.fryemuseum.org.