In August 1949, LIFE Magazine published a four-page spread on Jackson Pollock with the headline, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” This was virtually unheard of – never before had a magazine like LIFE given over so much real estate to a visual artist. Let alone to someone as provocative as Pollock, nicknamed “Jack the Dripper” for his novel style of drip painting.

That same year, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York purchased a painting by Andrew Wyeth, a contemporary of Pollock’s. In a unanimous decision, the museum’s board purchased Wyeth’s modest-sized painting from a New York gallery for $1,800 – then considered a major sum for a painting. That work, “Christina’s World,” still hangs in the permanent collection at MoMA.

However, not long after buying it, MoMA seemed to cast the painting aside. Today, “Christina’s World” hangs on a wall in a back hallway leading to the bathrooms. If MoMA’s treatment of the painting is any indication, Wyeth has become an outcast, a figure on the periphery of American modernism.

How did this happen? How did Pollock become the star of modern art history while Wyeth was relegated to the sidelines? In an exhibition of over 100 paintings and sketches, “Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect” at the Seattle Art Museum seeks to bring Wyeth back to the forefront. Though for many, he never really left.

Over the course of his 75-year career, Wyeth was by all accounts a very successful painter – his works were hugely popular with the American public, who crammed into his exhibitions at museums and galleries throughout the late 20th century. “Christina’s World” has become one of the most recognized images in American art, as much an American icon as Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.” Wyeth’s portrait of Helga Testorf entitled “Braids” from 1977 has even been nicknamed “The American Mona Lisa.” In fact, a case could be made that Andrew Wyeth was the greatest living painter in the United States during the mid-20th century, not Pollock.

Over the course of his 75-year career, Wyeth was by all accounts a very successful painter – his works were hugely popular with the American public, who crammed into his exhibitions at museums and galleries throughout the late 20th century. “Christina’s World” has become one of the most recognized images in American art, as much an American icon as Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.” Wyeth’s portrait of Helga Testorf entitled “Braids” from 1977 has even been nicknamed “The American Mona Lisa.” In fact, a case could be made that Andrew Wyeth was the greatest living painter in the United States during the mid-20th century, not Pollock.

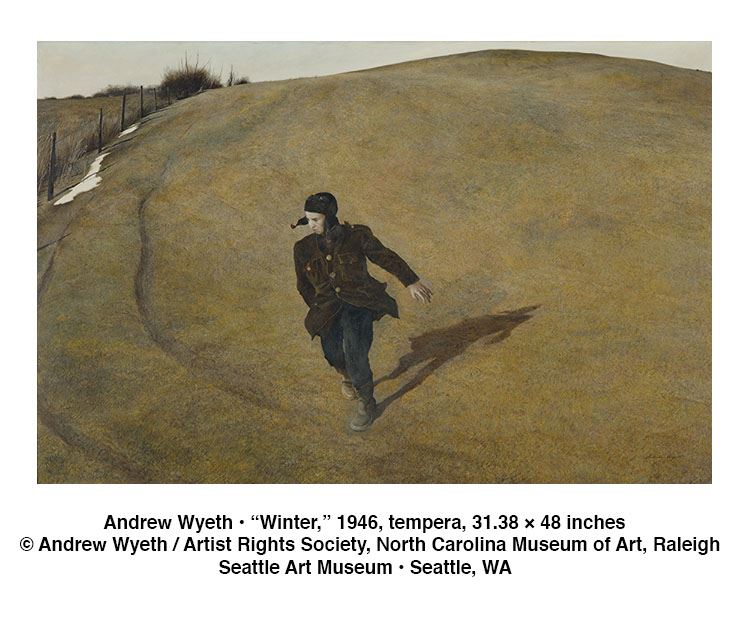

Many critics certainly felt this way. As one critic wrote in 1963, “In today’s scrambled-egg school of art, Wyeth stands out as a wide-eyed radical. For the people he paints wear their noses in the usual place, and the weathered barns and bare-limbed trees in his starkly simple landscapes are more real than reality.” For those who felt alienated and confused by the increasingly abstract nature of American modern art, Wyeth represented a breath of fresh air. His paintings begged – and still beg – to be read like books. Their stories and characters spill out beyond the frame, traveling between canvases in a twisting, turning, ever-evolving narrative. His evocative scenes of spooky farmhouses, empty fields, and mysteriously shored boats read like scenes from a movie – one where the dramatic tension has been cranked all the way up.

The SAM exhibition sets the stage for this eerily epic, sometimes salacious narrative to unfold. Opening with an introduction to Wyeth’s characters and scenes, the exhibit’s first room features a portrait of Wyeth’s wife Betsy next to a second portrait of his longtime neighbor Karl Kuerner. The rolling hills and Victorian farmhouses of Wyeth’s hometown of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania are also introduced – a place that looms large throughout his work, standing almost as a character itself.

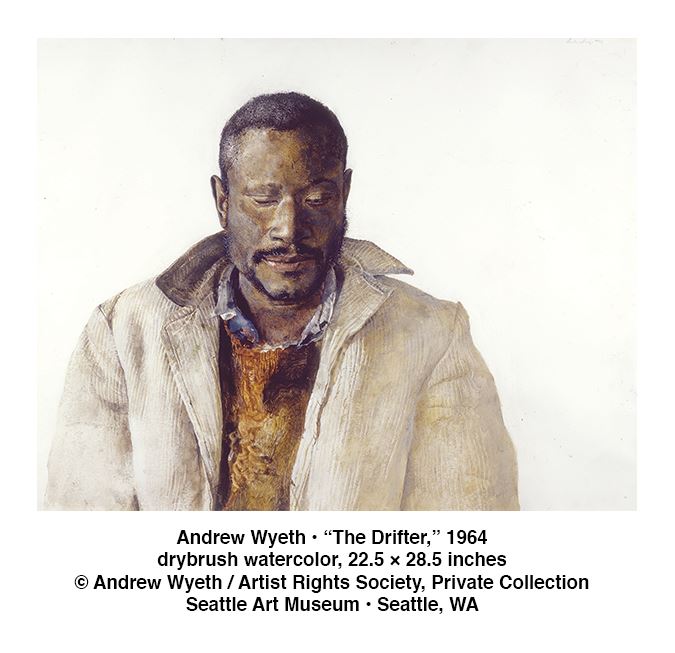

Explaining these people and places and laying bare his sources, the exhibit offers a new depth to Wyeth’s work. For many viewers, Wyeth’s characters may come to life here for the first time. When viewed alongside the preliminary sketches and wealth of expository material unearthed by curators Patricia Junker of SAM and Audrey Lewis of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, the people and places in Wyeth’s paintings become multilayered and complex. The exhibition also explores oft-overlooked aspects of Wyeth’s work, such as his fascination with film and the stories of his many African-American subjects.

Explaining these people and places and laying bare his sources, the exhibit offers a new depth to Wyeth’s work. For many viewers, Wyeth’s characters may come to life here for the first time. When viewed alongside the preliminary sketches and wealth of expository material unearthed by curators Patricia Junker of SAM and Audrey Lewis of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, the people and places in Wyeth’s paintings become multilayered and complex. The exhibition also explores oft-overlooked aspects of Wyeth’s work, such as his fascination with film and the stories of his many African-American subjects.

Ultimately, what the exhibition makes clear is that this narrative aspect of Wyeth’s work is what continues to draw people into his strange world. It is a narrative dripping with drama – mysterious deaths, secret mistresses, and dark familial tragedies. It is the narrative of Andrew Wyeth the person. It is the story of his life and the people and places he saw along the way – carefully and painstakingly observed in his meticulously crafted paintings.

More than that, though, it is the story of Wyeth’s inner world. The exhibition reveals that far from the dispassionate illustrator he is often accused of being, Wyeth was in fact filtering his world through a very opaque lens. A lens of desire and grief, longing and confusion, ownership and helplessness. To look closely at his paintings is to distinguish this lens, to see how it shaped Wyeth’s own perceptions of his world. It reminds us that we, in turn, bring our own distinct lens to the people and places we encounter. Like Wyeth, we are each crafting stories about the experiences of our lives. This is what makes us human.

This reminder of our shared humanity helps explain Wyeth’s continued relevance today, 100 years after his birth and despite continual shunning from the art world. While the high modernists of MoMA ultimately put their money on abstraction and artists like Pollock, it doesn’t make Wyeth’s realist style any less valid or meaningful. “Christina’s World” may still be hanging next to a bathroom – MoMA wouldn’t even lend it to be included in this show – but the painting remains one of the most captivating images in the canon of American art, and Wyeth one of its greatest artists.

Lauren Gallow

Lauren Gallow is an arts writer, critic, and editor. You can read more of her work at www.desert-jewels.com/writing.

“Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect” is on view through January 15 at the Seattle Art Museum, located at 1300 First Avenue in Seattle, Washington. Hours are Wednesday, Friday through Sunday 10 A.M. to 5 P.M.; Thursday from 10 A.M. to 9 P.M.; and closed Monday & Tuesday. For more information, call (206) 748-9287 or visit www.seattleartmuseum.org.