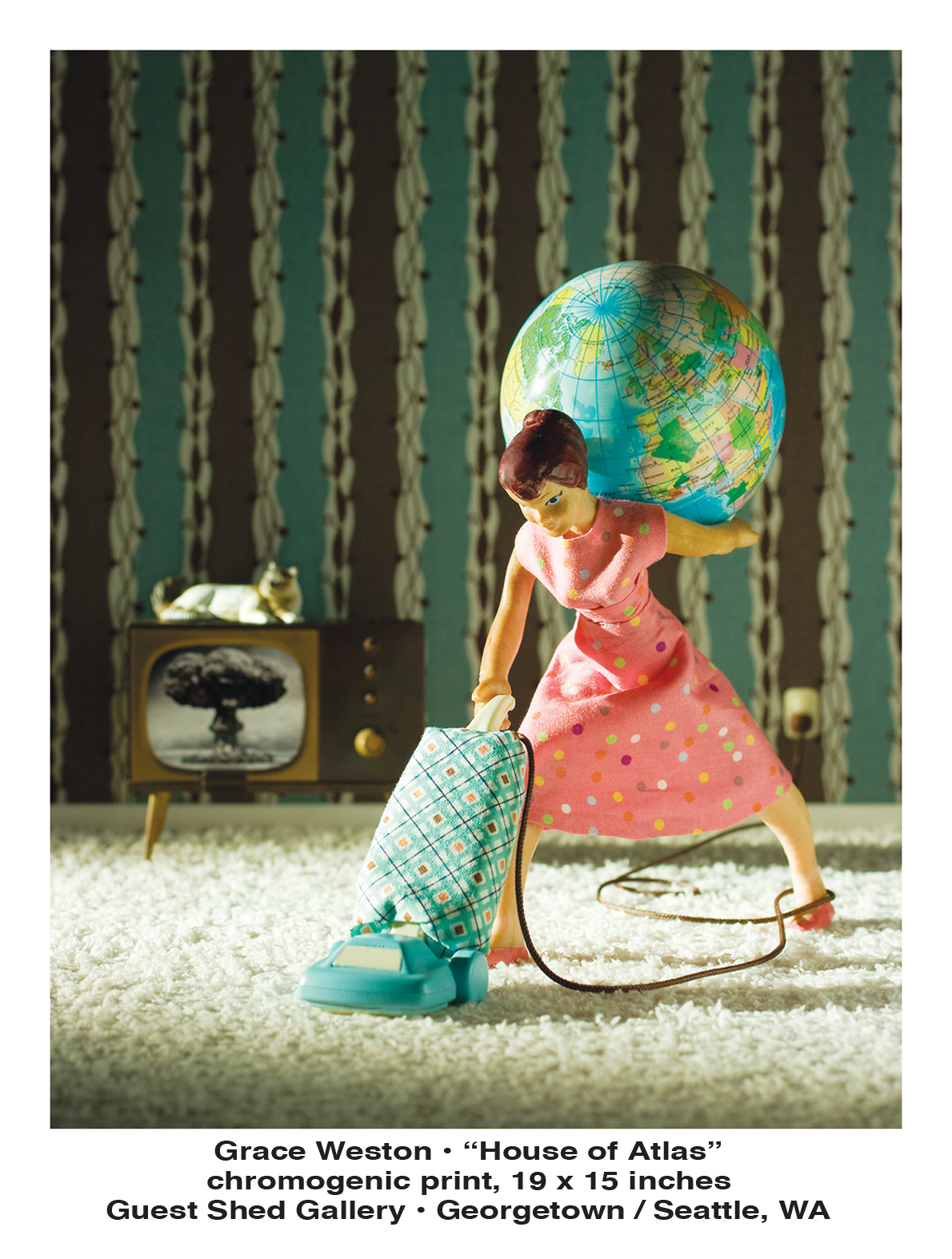

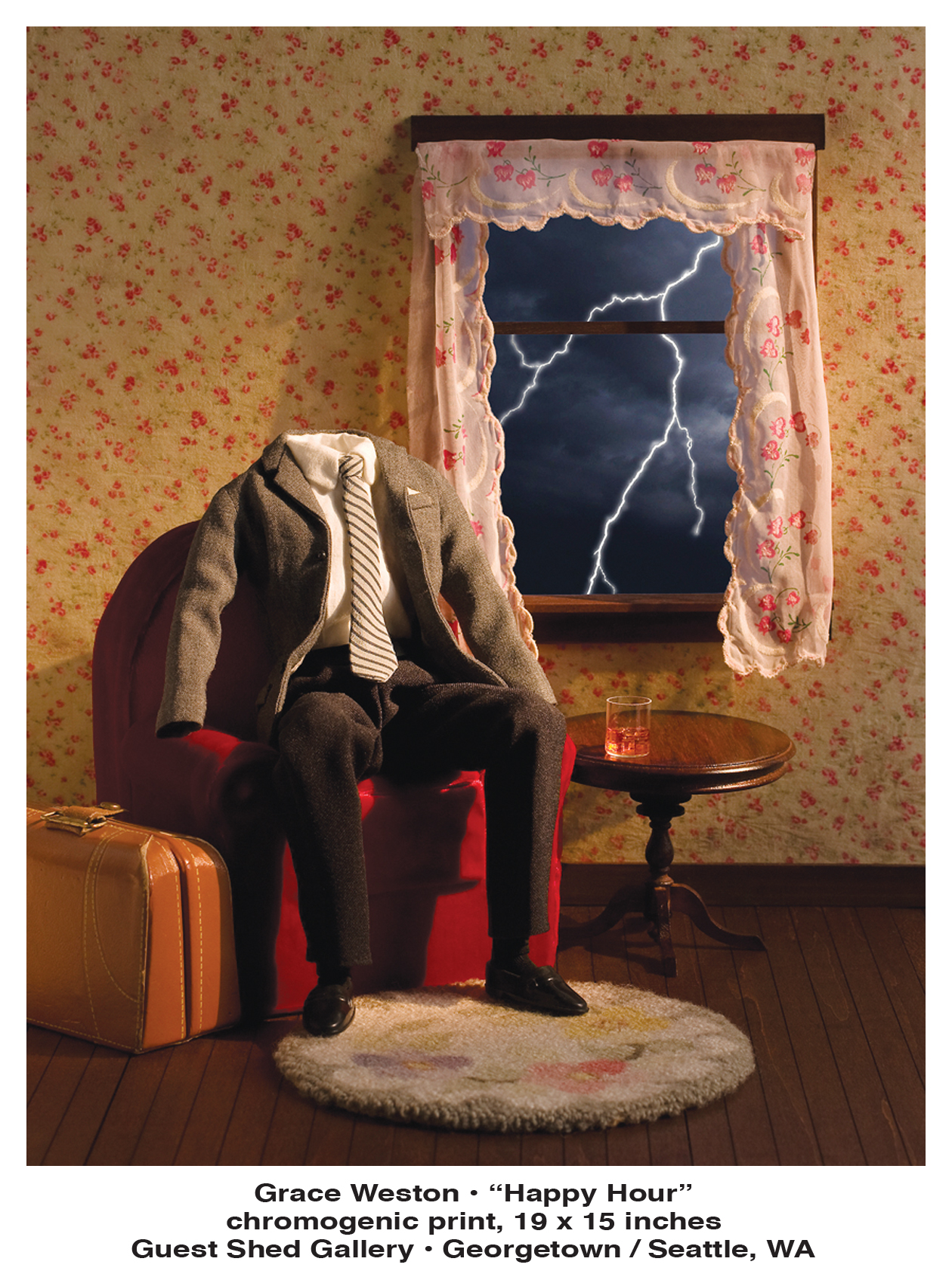

Grace Weston’s gorgeous, ironic, and often darkly funny photographs give the viewer both sensual and intellectual delights. Using miniature props, she creates vignettes of metaphorical psychological narratives, which she then photographs with vivid color and evocative lighting. The result is as alluring and hypnotic as a lucid dream, and as revealing of our subconscious fears and desires.

Weston is an award-winning artist whose work had been exhibited and collected widely in private and public collections in the United States, Europe, Scandinavia, and Japan. Her editorial clients include O, the Oprah Magazine; More Magazine; Discover Magazine; and several regional magazines.

Your artwork has so much story and depth. What are you exploring?

Grace Weston: I started to realize a number of years ago that my pieces are psychological. Like most people, or maybe I do it more than most people, I’ve got voices in my head. So much ties back to my being a kid—I was pretty isolated as a kid, and we lived in the woods. I’d run around the woods and have these out-loud conversations. It wasn’t imaginary friends, but just scenarios in my head of something

I would say to somebody. I had an active imagination.

In our society, there are so many contradictions, things that don’t make sense, or assumptions we make about one another or ourselves that are only assumptions. I love questioning that kind of thing or getting that out in a picture. An older, really straightforward example is the “Nitey Nite” picture where that little girl is in bed and she’s got three devils floating around her head. We’ve all had nights like that, haven’t we? I have. Where we’ve woken up, not being able to sleep because of anxiety, things I’m concerned about or worried about.

What are some themes you are interested in?

Grace Weston: I think making art is a lot about learning about yourself, and not in a selfish way, but in a conscious way. It’s a way to reveal things to yourself through the work. I think that helps the viewer discover things about themselves, too.

I know what the message is to me in my pictures, but I don’t like to spell it out all the way because the viewer can bring different things to it. Lots of times there are multilayers of meanings.

It’s almost as if we live on these two planes. We’re out in the world, interacting with people, doing our banking, doing our grocery shopping, keeping our lives together, having everything going, but I feel that we’re all walking around with our inner lives, too. It would be so interesting if we could really hear what everybody was thinking about in their soul. Not just their grocery list, but their questions about life, meaning, and connection, all of that. That’s what really interests me. And the fact that it is covered over with all the mundane things we do is fascinating to me, too.

Some of my pictures have an almost nostalgic, vintage look—the housewife, the 1950s father. It’s iconic. It represents a certain way things are supposed to look. I like when it’s the way things are supposed to look—but not. I like the idea that there’s this whole underground of feelings and thoughts and questions.

Some of my pictures have an almost nostalgic, vintage look—the housewife, the 1950s father. It’s iconic. It represents a certain way things are supposed to look. I like when it’s the way things are supposed to look—but not. I like the idea that there’s this whole underground of feelings and thoughts and questions.

How do you get your ideas?

Grace Weston: Sometimes I find a prop that inspires me. Or sometimes I find a prop that I feel one day I’ll use, and I put it in a drawer of my props. It can be years later that it shows up. Sometimes I have an idea first and I keep a little sketchbook where I’ll jot it down. Sometimes I’ll get a title first, and I have no idea what I’m going to do with it, but I’ll write it down because it sings to me somehow. Sometimes I’ll sketch a little idea, and then I’ll have to find the props or make the set and prop that will support the idea. Things change when I’m putting it together. Sometimes it’s spot on to how I imagined it, but usually it evolves.

When I first started the vignette work, my first shot was human scale. It was a bird cage on a stand and a curtain. That set me in the direction of the narrative vignette, but that was the last time I did human scale. I have more control over smaller props—there’s less storage involved, I don’t have to have an assistant, and sometimes I can move things and reach them as I look through the camera.

What sustains you as an artist?

Grace Weston: Having a supportive partner has made all the difference in the world to me. I feel that I have an art career because I have somebody who believes in my work. As an artist, you have to risk and do things and approach things in your art, where, when you’re right in the middle of it, you think, my God, this is awful, or stupid, or doesn’t everybody already know this? Or it’s obvious or redundant. But I don’t think you’re working your edge at all if you don’t have doubts. It’s great to have someone who says, “You know what you’re doing, keep going.” That makes a world of difference.

Christine Waresak

Christine Waresak is Seattle freelance writer and the founder of the website Constellation617.

This interview is excerpted and edited from an interview that appeared on the website Constellation617: Interviews with Creative People. To read the entire interview and other artist interviews, visit www.constellation617.com.

Portland-based artist Grace Weston’s artwork is in a group show at The Shed Studio and Guest Shed Gallery located at 739 South Homer Street in the Georgetown neighborhood of Seattle, Washington. The Shed Studio and Shed Guest Gallery holds its Grand Opening on Saturday, May 9, from 6-9 P.M., during the Georgetown Art Attack.

For more information about The Shed Studio and teh Shed Guest Gallery, visit https://www.facebook.com/shedstudioandguestshedgallery.

To view more of Weston’s work, visit her website at www.GraceWeston.com or Wall Space Gallery in Santa Barbara, California’s website at www.wall-spacegallery.com.