.jpg)

It’s not surprising that there’s a revival of interest in the life and work of Sister Mary Corita Kent (1918-1986). The only surprise is that she fell off the radar in the first place, and remains relatively unknown.

It’s not like Kent labored in obscurity. She was named woman of the year by the L.A. Times in 1966, and featured on the cover of Newsweek in 1967 (“The Nun: Going Modern”). In 1984, one of her designs sold more than 700 million copies (it was a popular, even iconic, U.S. postage “LOVE” $22 cent stamp)—but that was a special case, and anyway we are getting ahead of ourselves.

.jpg) Why the revival? For one thing, a favorable zeitgeist: social justice movements like BLM and #MeToo, the resurgence of progressive and activist voices in media and politics—all these resonate with Kent’s vision and convictions. She instigated happenings and be-ins before any of these things were a thing. Her work addressed world hunger, poverty, and the war in Vietnam, but all in a spirit of playfulness and hope. She titled one of her final prints “Yes we can.” It’s hard to imagine a more inspiring model—but we don’t have to imagine her, we just have to remember her.

Why the revival? For one thing, a favorable zeitgeist: social justice movements like BLM and #MeToo, the resurgence of progressive and activist voices in media and politics—all these resonate with Kent’s vision and convictions. She instigated happenings and be-ins before any of these things were a thing. Her work addressed world hunger, poverty, and the war in Vietnam, but all in a spirit of playfulness and hope. She titled one of her final prints “Yes we can.” It’s hard to imagine a more inspiring model—but we don’t have to imagine her, we just have to remember her.

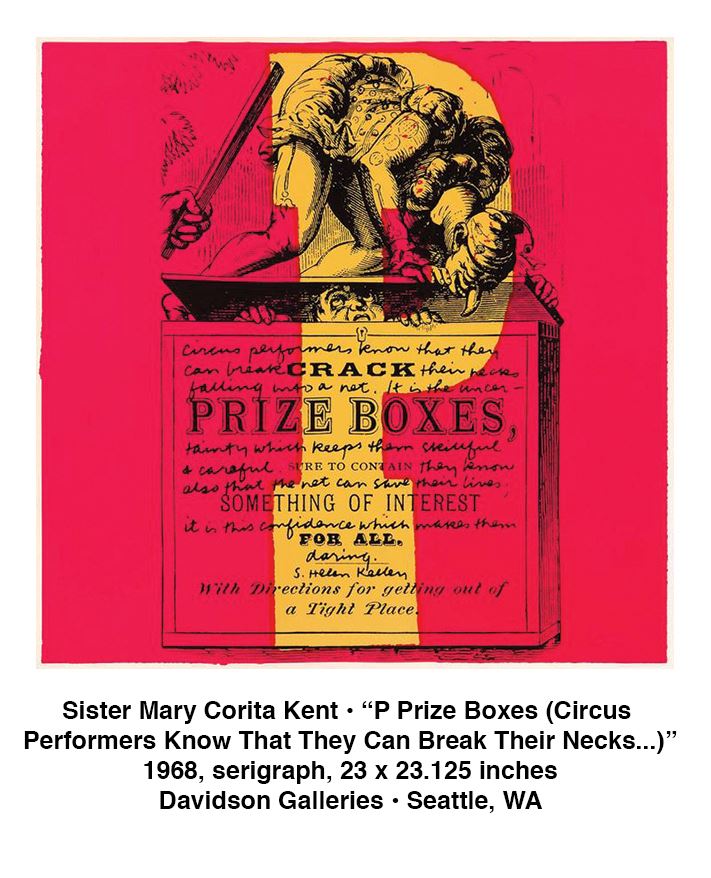

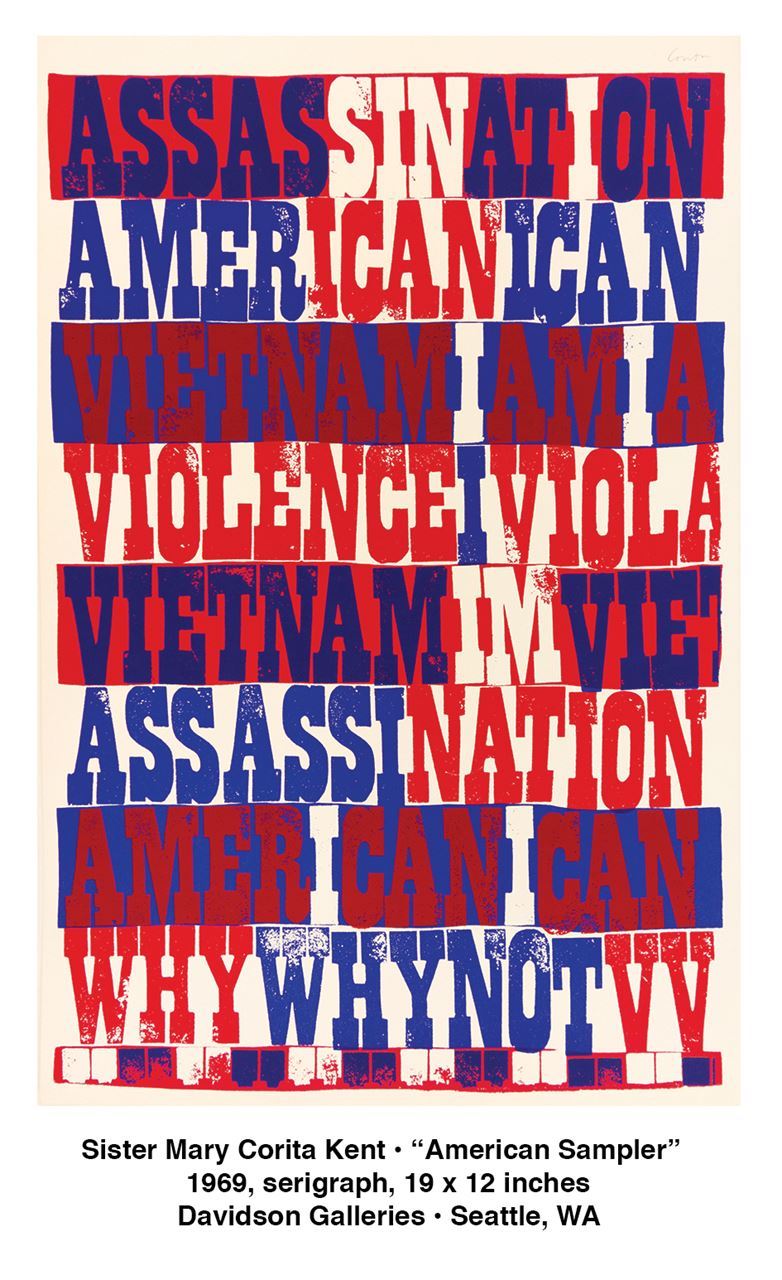

To this end, you can visit an exhibition at the Davidson Galleries, “Sister Mary Corita Kent: Speak Out.” This exhibit presents pieces from all phases of Kent’s varied career. Its focus is on the artist’s serigraphy, but the show also includes books she authored, and other surprises.

The artist was born Frances Kent in 1918. After high school she entered a Roman Catholic order, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. She took the name Sister Mary Corita Kent and taught art at the Immaculate Heart College in L.A. The college was a hotbed of liberalism and the avant-garde, and Kent its liveliest live-wire. It was her teaching methods, not her artwork, that drew visits from Charles and Ray Eames, Buckminster Fuller, and John Cage. (Her classroom rules still circulate on social media, though they are sometimes attributed to Cage, not Corita Kent.)

At IMC, Kent made art communally, democratically, allowing students and peers to decide colors, to contribute passages of text she might then draw into her creations. Art making as collaboration, as connectedness. Her tool of choice, screen-printing, was not only DIY, it was all about mass production: she meant her images to spread outward, to make impressions on as many minds as possible.

The “Speak Out” show includes several of Kent’s early pictorial works from the ‘50s—she made her mark with these, but it is not the work she is most known for. Muted in color, these prints deal with medieval religious iconography. They stand in contrast to the vibrant colors and free-flowing gestures that came later, but they are remarkable statements on their own terms.

In 1961, Kent saw the first solo show of an unknown commercial artist from New York, Andy Warhol (thirty-two Campbell soup can labels at L.A.’s Ferus Gallery). Pop Art energized the art world, but for Sister Mary Corita Kent it had deeper ramifications. It seemed to fit with the radical changes rippling through her faith: the reforms of Vatican II. Suddenly the Roman Catholic mass would not be in Latin but in the vernacular. Kent was already ahead of all these upheavals and she embraced them with gusto.

Kent began to include imagery from consumer culture. She appropriated Wonder Bread’s brand elements—those colored dots—but not as a nod to Warhol and his soup cans. She was riffing on the Catholic ritual of the Eucharist, the sacramental bread. And perhaps commenting on world hunger, a pressing problem of that time. Audacious moves like these, she felt, were aligned with Vatican II directives. (Her Archbishop came to see it differently; under pressure, Kent eventually left the sisterhood and moved to Boston.)

Text became central to Kent’s work. At first, excerpts from the psalms. Soon pop lyrics of the moment appeared. “Don’t you need somebody to love?” “Let the sunshine in.” “Help!” These she juxtaposed with longer passages from weightier sources—secular writers with a strong spiritual game were favorites (Whitman, Camus, Arendt). She quoted her renegade contemporaries, like Martin Luther King Jr., and the Jesuit priest Dan Berrigan, an anti-war activist who brought some disorder to his religious order.

Text became central to Kent’s work. At first, excerpts from the psalms. Soon pop lyrics of the moment appeared. “Don’t you need somebody to love?” “Let the sunshine in.” “Help!” These she juxtaposed with longer passages from weightier sources—secular writers with a strong spiritual game were favorites (Whitman, Camus, Arendt). She quoted her renegade contemporaries, like Martin Luther King Jr., and the Jesuit priest Dan Berrigan, an anti-war activist who brought some disorder to his religious order.

With her distinctive (and barely legible) handwriting, she set her texts within or between freeform shapes and brushstrokes, or scrawled within commercial letterforms ripped from billboards. (She dearly loved a good billboard.) A highlight of the “Speak Out” show is “American Sampler,” an almost purely typographic piece. The slab-serif letters in red, white, and blue ink have a menacing presence. Variations in color reveal shorter words within the larger words—“I CAN,” “SIN,” “NATION.” (Did she set the M, I, and A together as a reference to missing soldiers, or some other absence?)

Her later work took on an airier and more peaceful tone, as if a storm had passed. An example at the show is “The Common Dandelion” with its bit of Emerson “The invariable mark of wisdom Is to see the miraculous in the common.”

Kent did not confine herself to screen printing. She authored and illustrated books, and “Speak Out” includes some of these titles, including two from her “Believe” trilogy. The books may seem dated to you, unlike her prints, which appear to be ageless.

The show also includes some prominent commissions, including one of Kent’s most popular pieces, a US postage stamp, now iconic, with its six rainbow-colored strokes and the word “LOVE.” At Davidson Gallery, the stamps appear on a set of addressed envelopes—it is charming to see not just the design but the actual stamp itself in use, as designed, in all its commonplace ordinariness. Or do you see something extraordinary there, too?

The postage stamp may be Kent’s most recognizable image—the USPS issued more than 700 million of them—and it is certainly her smallest. But another contender for that “most recognizable” claim is the mural on the Boston Gas Company’s liquified natural gas storage tank, a 140-foot-tall container near downtown Boston. It is the largest copyrighted work of art on the planet, and yet it’s simplicity itself: six rainbow-colored strokes. (In this regard, the Boston Gas Company liquified natural gas storage tank and the tiny US Postal Service stamp are unified—talk about designs that scale well!) It is regrettable but understandable that the Boston Gas Company’s liquified natural gas storage tank will not be on display at the Davidson Gallery for this show. But you’ll be content to see the stamps, the books, and above all the marvelous prints of Corita Kent.

Tom McDonald

Tom McDonald is a writer and musician living on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

The “Speak Out” exhibition featuring art by Sister Mary Corita Kent, is on view November 5 through December 24, Tuesday through Saturday from 11 A.M. to 5:30 P.M. at Davidson Galleries in Seattle, Washington. For more information, visit www.davidsongalleries.com.