We all think we know the photographs of Edward Curtis from a handful of frequently reproduced images that offer us romanticized, nostalgic views of Native Americans from the turn of the twentieth century, a time when Native peoples were thought to be vanishing. Curtis set out to preserve their traditional way of life, when it was already almost destroyed by assimilation efforts by the US government.

We all think we know the photographs of Edward Curtis from a handful of frequently reproduced images that offer us romanticized, nostalgic views of Native Americans from the turn of the twentieth century, a time when Native peoples were thought to be vanishing. Curtis set out to preserve their traditional way of life, when it was already almost destroyed by assimilation efforts by the US government.

This summer, on the 150th anniversary of Curtis’s birthday, the Seattle Art Museum along with many nearby museums and cultural centers, is reexamining his work, his legacy, and his relationship to contemporary native culture and art.

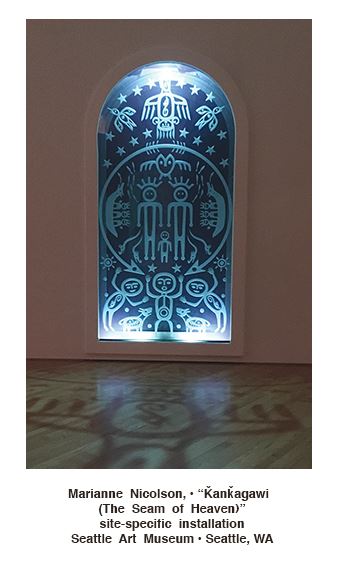

At the entrance of “Double Exposure” at the Seattle Art Museum, a voice in Lutshootseed and English welcomes us, as we are immersed in the stunning installation by Marianne Nicholson. Two back to back glass panels, etched with native imagery, and a light inserted between them, cast shadows on the floor. Ḱanḱagawi (The Seam of Heaven), metaphorically presents the Columbia River, in its beauty and disruptions. The name means “sewn together.” The two pieces of glass suggest the breaks caused by dams and borders, while the light and shadows offer possible healing as the treaty between Canada and US comes up for renegotiation.

“Double Exposure” features 150 historical images by Curtis, a selection from various chapters of The North American Indian, created between 1907 and 1930. The book is available online at http://curtis.library.northwestern.edu and well worth reading even a short excerpt from the detailed information that originally accompanied the photographs.

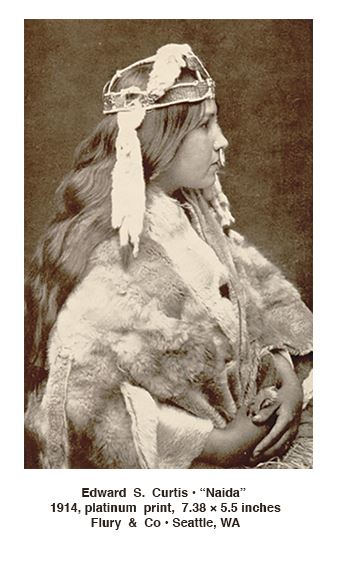

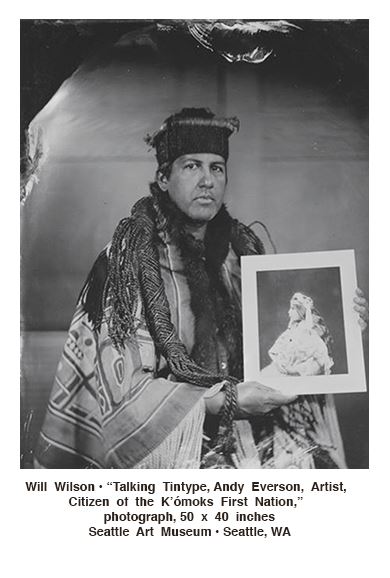

Curtis created 40,000 photographs of more than 80 tribes, but they were meant to be seen in the context of tribal history, customs and much more. His accomplishment is staggering. His assistants also made 10,000 wax cylinder audio recordings of music, a few of which we can hear in the exhibition. We also can watch his pioneering film from 1914(!) “In the Land of the Headhunters” starring Naida as the bride. Her descendant holds the Curtis photograph in Will Wilson’s tintype.

The stunning photogravure images, created on copper plates, glow on the wall. We revel in Curtis’s eye for composition, and his technical facility with a complex photographic process. Curator Barbara Brotherton offers detailed and nuanced labels. In some cases these images are posed works that followed Curtis’s romantic perspective, in others they document historical practices that had mainly been passed on through oral traditions.

For more immersion into Curtis’s technical prowess, Flury & Co, our local Curtis specialists offers “Edward Curtis Photographs in Copper” (On view through September 30) featuring 30 copper plates, never before displayed, from the original North American Indian publication. Flury & Co is a like a small museum in itself. The family have rights to the sale of Curtis prints and plates, memorabilia and manuscripts, acquired directly from the artists descendants living in Seattle.

In “Double Exposure,” we also can experience native commentary on Curtis. First, there is a new way to insert videos into an exhibition, the app “Layar.” As we scan a Curtis photograph of a canoe race, a video appears with an interview with a 16 year old youth who participates in contemporary canoe journeys. He speaks vividly of the endurance required to paddle a canoe as a team for 10 hours straight.

In “Double Exposure,” we also can experience native commentary on Curtis. First, there is a new way to insert videos into an exhibition, the app “Layar.” As we scan a Curtis photograph of a canoe race, a video appears with an interview with a 16 year old youth who participates in contemporary canoe journeys. He speaks vividly of the endurance required to paddle a canoe as a team for 10 hours straight.

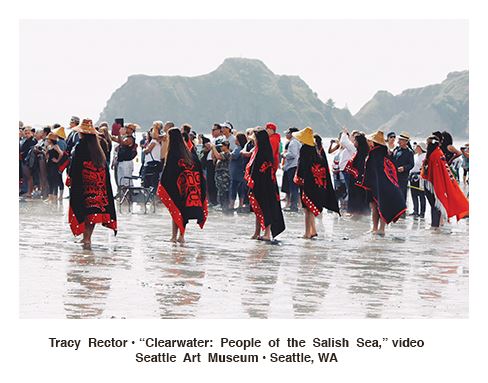

This dramatically layering of the Curtis photograph with contemporary interviews by native speakers makes a dynamic intersection of past and present. Will Wilson’s large tintypes come alive as we scan them and hear from the contemporary person photographed, a poet, a state politician, an artist, a filmmaker, a drummer, a dancer. Tracy Rector’s experimental films record contemporary natives speaking of the threat of environmental contamination as well as the preservation of rituals and traditional practices.

The exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum is one part of “Beyond the Frame: Being Native” a collaboration of 20 native groups and cultural institutions reexamining Curtis in a contemporary context. Just up the street from the Seattle Art Museum, the Seattle Public Library offers “Protecting the x əlč: Indigenous Stewardship of the Salish Sea” (On view through August 15). It has two parts; the first room emphasizes Curtis’s photographs of traditional practices such as fishing and harvesting (including historical artifacts); the second room presents contemporary life as in the flourishing canoe journeys, the success of the dam removal on the Elwha River, and contemporary resistance to industries, such as the Lummi defeat of a coal terminal on Cherry Point. Concluding the exhibition is a video with Brian Cladoosby president of the National Congress of American Indians and Chairman of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, speaking about their pioneering plans to resist the effects of climate change.

For a complete list of the exhibits and events affiliated with “Beyond the Frame: Being Native” as well as information on contemporary native life see the website. https://www.beyondtheframe.org. Look out in particular for the exhibition of 20 contemporary native artists, curated by RYAN! Feddersen with Chloe Dye Sherpe, “In Red Ink,” at the Museum of Northwest Art in La Connor that opens on July 7. Also don’t miss RYAN! Feddersen’s amusing installation at the end of “Double Exposure” in which we take on the role of “post-human” types such as “Humans of the Glass Offices” and “Vanishing Human Types: People of the Outdoors,” echoing Curtis view of natives as the “vanishing race.” It’s online at http://posthumanarchive.site.seattleartmuseum.org.

We are fortunate here in the Northwest to have a vibrant contemporary native art and cultural flowering that is gaining increasing visibility throughout our region thanks to the collaboration of traditional institutions with committed and articulate tribal groups in Washington, Oregon, and Canada.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com and for local, national, and international publications.

Seattle Art Museum

1300 First Avenue, Seattle, Washington

Flury & Co

322 First Avenue S., Seattle, Washington

Museum of Northwest Art

121 N 1st Street, La Conner, Washington