On the front door of Peter Miller Books in Pioneer Square is a sign:

NO CELL PHONES.

NONE AT ALL. THANK YOU.

The message is direct, stylish, and polite—not unlike the shopkeeper, Peter Miller, who will have a bright welcome for you as you enter. The sign suggests that the space you are entering is a kind of respite.

Step inside. Books are everywhere. Mostly about art, design, and architecture. Big thick tomes from prestige publishers like Phaidon, Taschen, and Rizzoli. Softcover books from small presses. Books on typography, books on color, books on flowers and gardens. Books on landscape design, interior design, graphic design, urban-, industrial-, and information design. Books about writing, books about books.

Step inside. Books are everywhere. Mostly about art, design, and architecture. Big thick tomes from prestige publishers like Phaidon, Taschen, and Rizzoli. Softcover books from small presses. Books on typography, books on color, books on flowers and gardens. Books on landscape design, interior design, graphic design, urban-, industrial-, and information design. Books about writing, books about books.

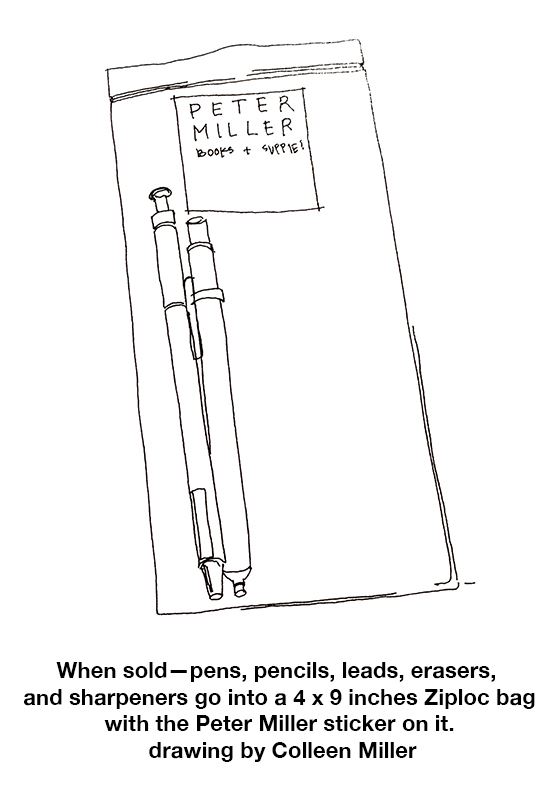

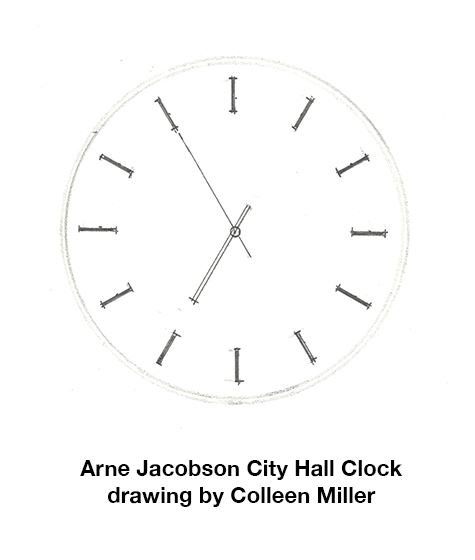

But not only books. You find fountain pens and mechanical pencils. Sketch pads and journals, briefcases and shoulder bags. There are lights and lamps to purchase, and then to read by, or to work under. Unexpected themes emerge—one of them is Time: there are stylish clocks and watches, and on every wall a fetching wall calendar.

Speaking of walls, admire the shop’s brickwork for a minute, and the thick cedar timber beams above—feel the solidity and presence of the shop itself. Everything has been considered. Hear the symphonic music playing—it emanates from a compact Tivoli radio—Miller keeps various colors in stock. And now, turning the corner, the next theme: cooking utensils and dish towels, espresso makers, juicers, pepper grinders.

If you have questions at this point, the place to find answers is in Shopkeeping, a new book written by Peter Miller, publication date May 7th.

The book is not a manual, or a how-to. It’s more of a why-to. But it describes how the 44-year-old shop came to be, and came to be curated in this curious way. It answers the question of how Peter Miller Books became the iconic place that it is—with supporters and patrons the world over—despite missteps, despite relocations in the face of rising rents and other pressures. How does a store become more than a store but a touchstone for a thriving creative community?

The book is not a manual, or a how-to. It’s more of a why-to. But it describes how the 44-year-old shop came to be, and came to be curated in this curious way. It answers the question of how Peter Miller Books became the iconic place that it is—with supporters and patrons the world over—despite missteps, despite relocations in the face of rising rents and other pressures. How does a store become more than a store but a touchstone for a thriving creative community?

Seattle had little going for it, architecturally speaking, when Miller settled here in the early 1970s; the region’s economy was in decline (Boeing layoffs). What was he thinking? And yet five decades later Seattle has an embarrassment of architectural riches. Buildings by Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Steven Holl (among other luminaries); it has Olympic Sculpture Park, renowned for its transformation of urban space as much as for its artworks by Louise Bourgeois, Richard Serra, and more. But Seattle also gave rise to Costco and to Amazon with its One-Click buying and same-day deliveries. Those developments spelled death for any number of small shops, and drained the vitality and sense of purpose from the core of small towns everywhere. There’s a reason why Miller carries four different editions of The Life and Death of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs. And a reason for adding one more book to the shelves with Shopkeeping.

Jacobs, Walter Benjamin, and other thinkers have written about the vital role that small shops play in creating a vibrant city. But until now we’ve not heard from actual shopkeepers. Theory is great, case studies wonderful, but what is it like, in practice, to keep a shop running so well and for so long?

You don’t need to or want to run a store to relate to Miller’s tale. Your spirits will sink when you read about the shop getting broken into, or the time it flooded. And you will exult at that moment when a customer orders one copy of every book in the shop, for a design school starting up in Japan. (That one transaction turned a bleak sales season into a rosy one.) The advice in Shopkeeping seems applicable to anyone pursuing any creative pursuit that is their own. “It is the great difficulty of running a shop—the fragility of your own confidence and optimism. You are the steward of an invented form, and it is your huff and puff that gives it life.”

You don’t need to or want to run a store to relate to Miller’s tale. Your spirits will sink when you read about the shop getting broken into, or the time it flooded. And you will exult at that moment when a customer orders one copy of every book in the shop, for a design school starting up in Japan. (That one transaction turned a bleak sales season into a rosy one.) The advice in Shopkeeping seems applicable to anyone pursuing any creative pursuit that is their own. “It is the great difficulty of running a shop—the fragility of your own confidence and optimism. You are the steward of an invented form, and it is your huff and puff that gives it life.”

To run a small shop day in and day out doesn’t exclude travel, and Shopkeeping is in some ways a travelogue. We have scenes from Belltown, Pioneer Square, Bozeman, Milan, Copenhagen, and Sydney, Australia (where Miller finds a “very brave” food shop). Magic and serendipity are necessary tools in the shopkeeper’s kit, but you never know where the magic will happen: one of Miller’s best finds, a treasure trove of architecture books, fell into his hands in Anacortes, Washington. Same with customers: someone browsing the store may exit without saying a word, or they may buy one of everything, or turn out to be Rem Koolhaas. Many items in the shop are well-travelled too. Miller likes to share their backstories—I enjoyed the mini-history of calendars in Italy, the inside scoop on the drama behind graphite pencils. Every item has a story, and every shopper. But the book’s main protagonist is always the shop itself.

Shopkeeping is thoughtfully put together, full of surprises, a joy to read. Miller’s a uniquely gifted writer. Colleen Miller’s charming illustrations bring space and light to the text.

Shopkeeping is thoughtfully put together, full of surprises, a joy to read. Miller’s a uniquely gifted writer. Colleen Miller’s charming illustrations bring space and light to the text.

As architects like to say, “Only common things happen when common sense prevails.” Peter Miller Books is no common shop, and Shopkeeping is no common book.

Tom McDonald

Tom McDonald is a writer and musician living on Bainbridge Island, Washington.

Peter Miller Books located at 304 Alaskan Way South, between South Jackson and South Main Street in Post Alley, in Seattle, Washington, is holding a book launch on Wednesday, May 8, 4-6:30 p.m. Visit www.Petermiller.com for more information.