Gallery Onyx, the phenomenal showcase for artists of African descent in Seattle, has just opened a second venue in the chic Arte Noir space at 23rd and Union in Seattle, Washington!

The only gallery in Seattle with two venues, Gallery Onyx started with only seven artists in a small space in Belltown in 2015. Now it includes over 400 artists in its collective. You can currently see 33 artists in their ongoing “Members Exhibit” at Gallery Onyx Pacific Place. Gallery Onyx Midtown Square is showing 46 artists in the exhibition “Truth B Told II” selected from their portfolio of the same name. The new space is larger than the original gallery with movable walls that create a dynamic presence.

The only gallery in Seattle with two venues, Gallery Onyx started with only seven artists in a small space in Belltown in 2015. Now it includes over 400 artists in its collective. You can currently see 33 artists in their ongoing “Members Exhibit” at Gallery Onyx Pacific Place. Gallery Onyx Midtown Square is showing 46 artists in the exhibition “Truth B Told II” selected from their portfolio of the same name. The new space is larger than the original gallery with movable walls that create a dynamic presence.

When you enter Gallery Onyx, it is obvious that it follows a unique path: rather than a homogenous look, with just one or two artists, it juxtaposes dozens of artists of all styles and media, from abstract to realistic, from expressionist, to surreal, from mosaics to digital prints. Earnest Thomas, President and Co Founder of Gallery Onyx focuses on inclusiveness, rather than a marketable style from an artist. He encourages young artists, bashful artists, artists who have never show their work before. Gallery Onyx mission is to “educate, inspire, cultivate, and showcase the artwork of artists of African descent from our Pacific Northwest communities.”

This mission is meeting with great success. As you read the biographies of the artists in the Gallery Onyx portfolio “Truth B Told II,” that includes 276 artworks by 74 artists, formal art training does not dominate the narrative. The Onyx artists came to art while pursuing full time jobs, professional careers, and/or military service. Some took up art after a medical condition prevented them from working. Some began to draw as two year olds, but never went to art school, others took it up as elders. The range of experiences that these artists bring to their work inspires us, telling us that creativity can blossom no matter what stage or age in life.

Both of the Onyx galleries are welcoming, comfortable places where artists can interact with customers and each other. The movable walls can easily be reconfigured. Thomas, like Vivian Phillips, Arte Noir Executive Director, deeply believes in the power of community. Earnest Thomas seeks to “uplift the soul to soul communication that art brings.” Arte Noir’s vision is to create “space, stability, opportunity, and training to serve the needs of the Black creative community with a permanent location at Midtown Square.”

Arte Noir’s boutique sales gallery features artist-designed products by some of the same artists, as well as those shown in the spectacular murals in Midtown Center’s courtyard and on the outside walls of Midtown Center.

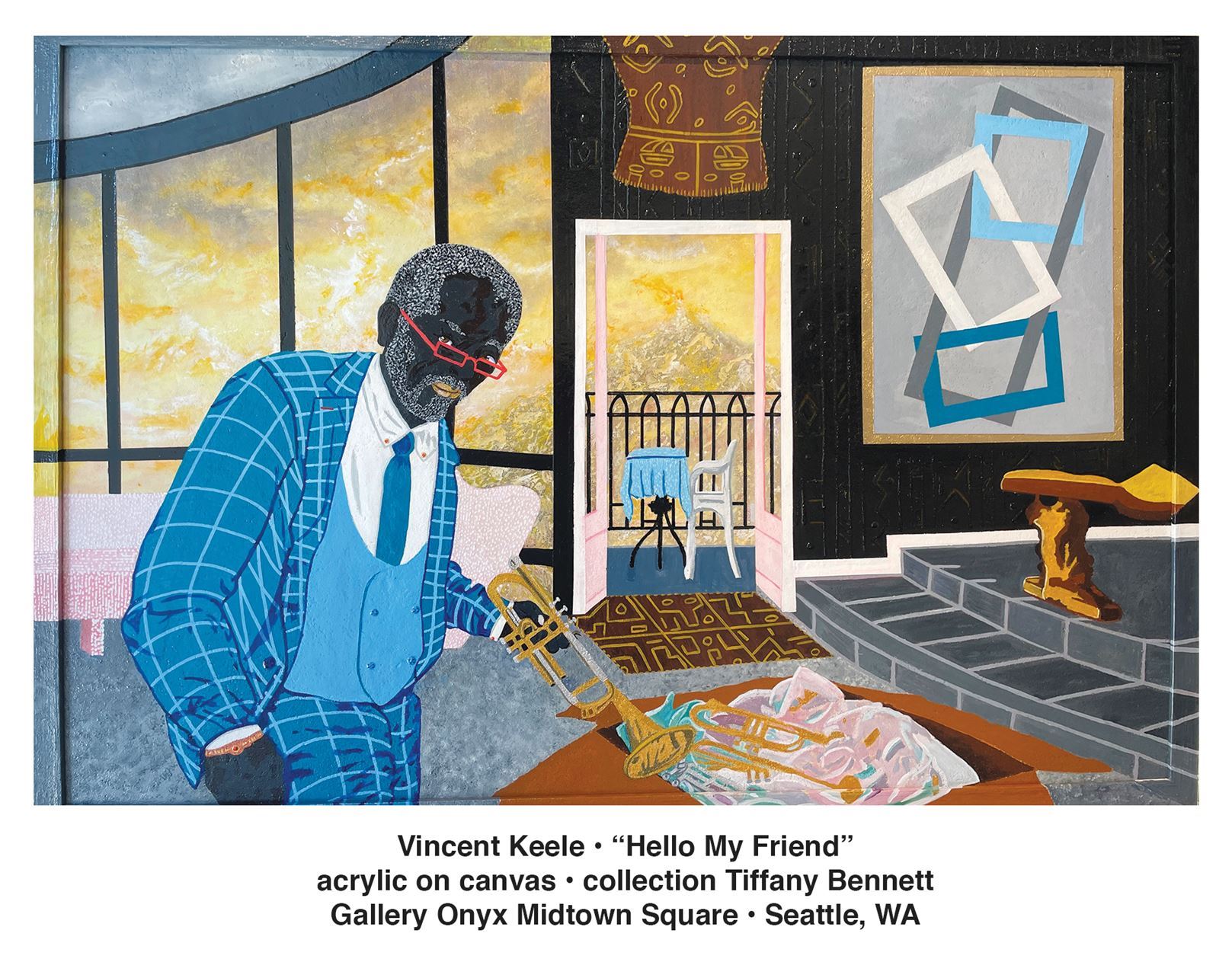

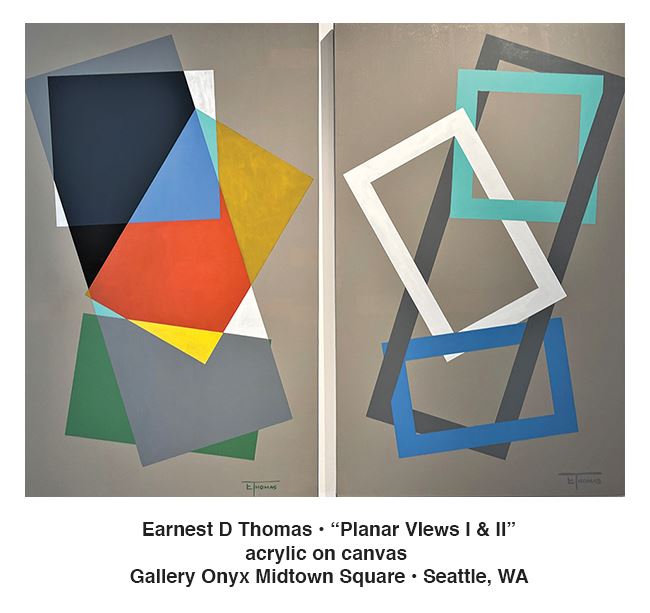

Highlighting a few works in “Truth B Told II” is difficult! “Hello My Friend,” by Vincent Keele, is a portrait of Earnest Thomas that depicts the interior of Thomas’s house with his painting in the background. Next to it in the gallery is that same painting “Planar Views I and II,” two adjacent canvases with the same structure of rectangles and squares, but on the right the open frames in single colors intersect to suggest an unsolvable puzzle, while on the left opaque planes, with many of the same colors, create a different dynamic entirely.

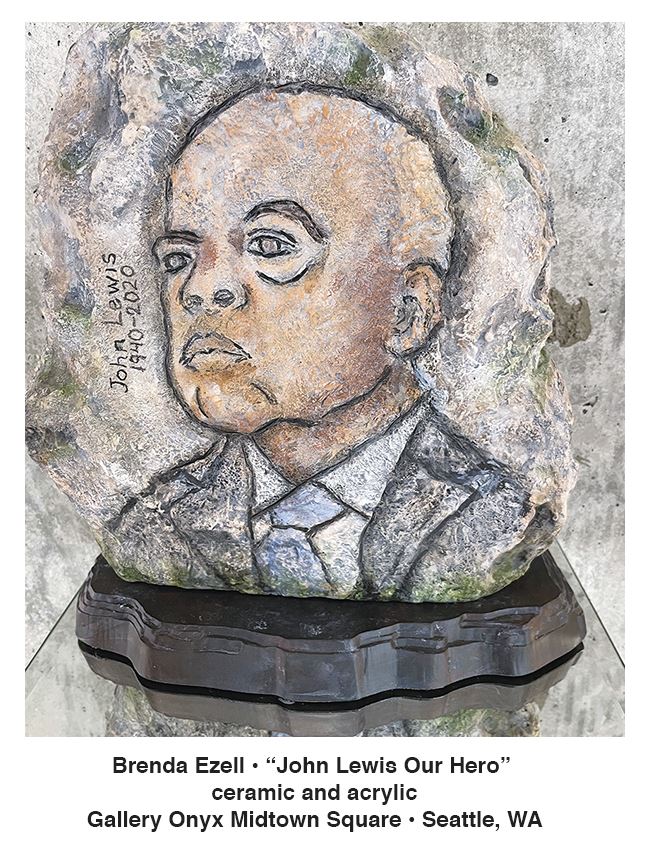

The portrait of John Lewis “Our Hero” in acrylic and ceramic by Brenda Ezell pays intimate homage to a great leader suggesting his intense life of commitment to Civil Rights.

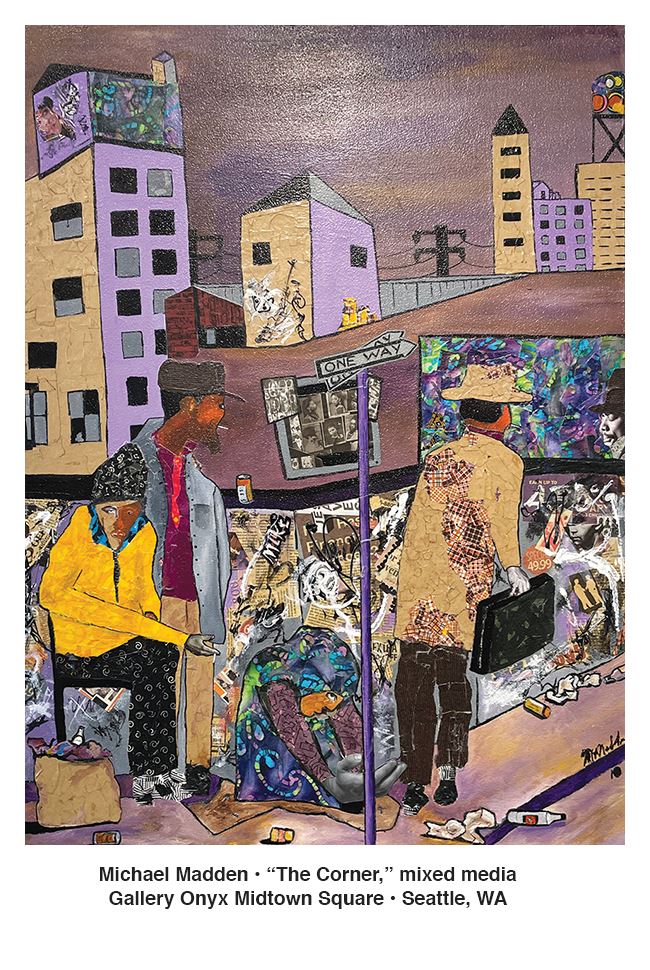

Michael Madden’s “Street Corner” includes collage, oil paint, and drawing, as well as embedded photographs. Its multiple complex levels suggests the experience in Seattle these days, from proud histories to desperation.

“Amboseli” by Jackie Nichols, with beads, leather, and metal sewn into the surface honors a Masai warrior that she met in the Amboseli National Park in East Africa. It is one of several works with an African theme.

Bryan Stewart’s “Presence,” a tall narrow half portrait of a black man looks down on us with serene dignity.

The new Gallery Onyx Midtown Square paired with the Gallery Onyx at Pacific Place allows these artists to reach a wide audience. Throughout the entire Midtown Complex with its extensive art program, we can experience the flowering of contemporary artists of color in the Central District and the versatility of artists of African descent.

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt

Susan Noyes Platt writes a blog www.artandpoliticsnow.com and for local, national, and international publications.

Gallery Onyx, located at Pacific Place, 600 Pine Street, in Seattle, Washington, is open from Friday through Sunday, from 12 to 6 P.M.

Gallery Onyx Midtown Square, located inside Arte Noir, 2301 E. Union, St Suite H, in Seattle, Washington, is open Tuesday through Saturday from 10 A.M. to 6 P.M.